"Things Just Sort of Keep Happening" (Summer, 1962)

The joy--and pain--of really, really, really bad baseball

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics. Welcome to all new readers/subscribers, and if you like what you’re reading, please join the mailing list and share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing. (It’s still FREE to join the list: Just click “None” on the “subscribe now” page.) The best way you can help out is by spreading the word and sharing with others. I have set up payment tiers, if you wish to chip in and allow me the time to do a little more research on on these posts and have full access to the archives—I’ve made those subscriptions about as cheap as Substack will let me make them, which is $5 a month or $40 a year.

I.

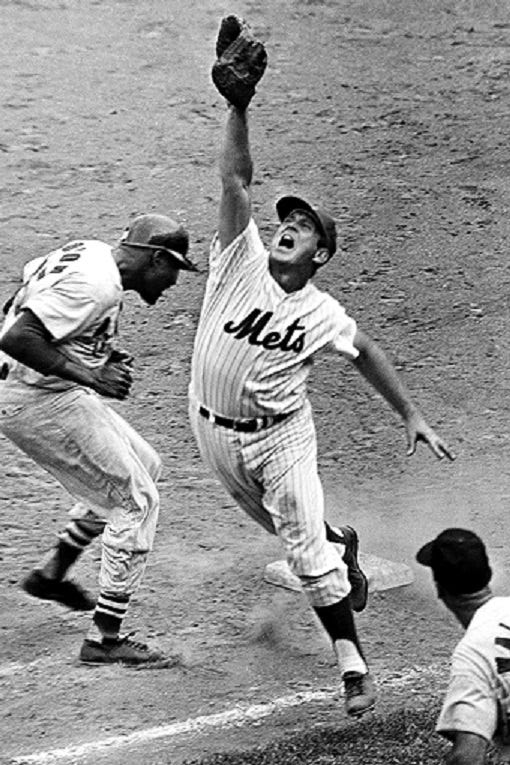

One day in the summer of 1962, a major-league baseball player hit a long drive to right-center field at the old Polo Grounds in New York City. This would have been a certain triple for most hitters, except that the man who hit this ball was named Marv Throneberry, and these were the 1962 Mets, a player and a team whose identity revolved entirely around their own ineptitude.

Already that day, Throneberry, playing first base, had botched a rundown of a Cubs player by standing directly in his path and getting called for obstruction, allowing Chicago to score four additional runs. Now, Marvelous Marv was trying to make up for it by chugging into third base. He stood there, hitched his belt, caught his breath, and then watched as the Cubs’ Ernie Banks caught the ball and stepped on first base. The umpire called him out, because Marvelous Marv had not even come close to touching first base.1

“Things just sort of keep on happening to me,” Throneberry said, and things just kept happening to the Mets that summer as they lost 120 games. And Marv Throneberry? Marv Throneberry, like no one before him and no one since, made a living out of his ineptitude. And the 1962 Mets are fondly remembered the most joyously awful team in baseball history.

II.

All of this is captured in Jimmy Breslin’s Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game, a thin and oft-neglected volume which is perhaps the funniest baseball book ever written. Breslin captures both the absurdity of the Mets’ play on the field and the unlikeliness of their very existence, which happened only because the Giants and the Dodgers chose to leave New York City in the late 1950s, and the powers-that-be began to argue that New York could not subsist with a single baseball team. “I know New York,” said Kenneth Keating, who would become a United States Senator in 1959. “It is not used to a having a single loyalty to a single team. This is a city which must have divided interests.”

And so one day, the mayor of New York, Robert Wagner, called a well-placed lawyer named William Shea, who began a years-long lobbying campaign to bring a National League baseball team to New York City. At one point, he and Branch Rickey proposed starting up a third league, the Continental League, and politicked in Congress to challenge baseball’s anti-trust laws. The owners had no choice; in order to quell the threat, the National League agreed to expand to Houston, and to New York.

And so the Mets became a thing that was happening, and then they became The Mets, and the haplessness of the first season of their existence came to define them as the anti-Yankees, a franchise that can not and will not ever get out of its own way. The city where they were born has come to love them for what they are, a dysfunctional and often unintentionally hilarious disaster. But they are there in Queens, and they have a deep-pocketed owner who actually seems to care about winning, which is something that cannot be said of the baseball team across the country in Oakland, California.

III.

The other night, I made the mistake of turning on a baseball game between the Oakland Athletics and the Boston Red Sox. The A’s were losing by seven runs, on the way to their eighth consecutive defeat. They had struck out 13 times against a Red Sox relief pitcher named Nick Pivetta, who was apparently not skilled enough to stick in the starting rotation for a Red Sox team that’s a bottom-feeder in its own division this season. The announced attendance at the Coliseum in Oakland that night was a bloated 9,987, but in truth, there were barely enough people there for a minyan. To call the atmosphere funereal would be an insult to the raucous nature of your average mortuary.

There are a lot of unhappy denizens here in Oakland these days, as it lurches its way back from a global pandemic. And unfortunately the A’s have come to represent the city’s collective post-COVID depression. They are a franchise without hope, owned by perhaps the worst owner in the history of sports, and while they will probably win just enough games in the next two months to avoid eclipsing the Mets as the worst team in baseball history, they will likely serve as a symbol of an era when the region that surrounded them was struggling with its own image. And then, after that, they will likely be gone, and just as New York briefly became a one-team town, so, too will the Bay Area—a region of nearly eight million people, which is almost exactly what the population of New York City was in 1960.

Often, there is an underlying joyousness to prodigious losing, to knowing that is a temporary state, to realizing that it can only get better from here. (Years ago, I spent time with one of the worst college basketball teams in the country, and it was a joy to write, because the team’s head coach had the perspective and the foresight to realize that something better was on the horizon. Turns out he was correct.) That’s how it was in New York in 1962. That’s how it was for Jimmy Breslin, who understood that the Mets were the beginning of something better for the city, even if those people who eventually became Mets fans would spend the next six decades questioning their own sanity. “Now we have the Mets, and that’s the way it should be,” he wrote of New York getting a National League franchise. “We’re with familiar things again.”

Someday, I would love to look back on this season in Oakland and view it as a horrific aberration, engineered by a first-class asshole with nothing better to do with his prodigious fortune. Someday, I’d like to think that we will remember the days when Oakland almost lost its baseball team until the incompetence of both a vacant owner and a duplicitous commissioner tripped up their grand plans, and someday, I’d like to think we’ll laugh about the days when the A’s fielded a lineup stacked with dudes who make Marv Throneberry look like Darryl Strawberry in his prime. But right now, things just keep happening, night after night after night.

This newsletter is a perpetual work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Reply to this newsletter, contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please join the list and/or share it with others or consider a paid subscription.

The story became such a mythologized encapsulation of the Mets’ ineptitude that is now widely believed that Throneberry also missed second base.

When I saw your link to your column about the worst team in college basketball, I assumed it was going to be about Penn State during one of their regular (and lengthy) troughs over the decades. Nope - thank you, Towson! 😁

I saw the Amazin Mets play several times. There was a promotion at a local supermarket where you could buy a ticket for a game for less than parking. But we got to see aging stars like Duke Snyder and Richie Ashburn. Then there were characters like Casey Stengel who had his own language and of course Marvelous Marv. Reading about them in the Daily News was a blast.