"He serves at the pleasure of the owners" (1920)

Secrets, lies, and sports commissioners.

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics. Welcome to all new readers/subscribers, and if you like what you’re reading, please join the mailing list and share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing. (It’s still FREE to join the list: Just click “None” on the “subscribe now” page.) The best way you can help out is by spreading the word and sharing with others. I have set up payment tiers, if you wish to chip in and allow me the time to do a little more research on on these posts and have full access to the archives—I’ve made those subscriptions about as cheap as Substack will let me make them, which is $5 a month or $40 a year.

I.

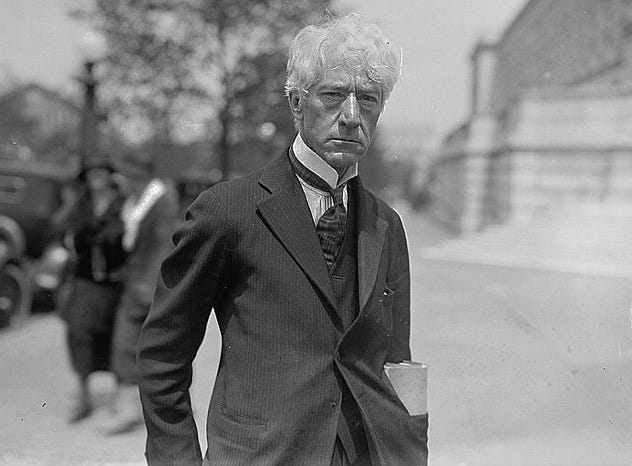

The first true commissioner in American sports was named after a Civil War battle during which his father, a surgeon, was wounded while performing an amputation. The commissioner’s full name was Kenesaw Mountain Landis, and he lived up to his theatrical moniker, with a sweeping mane of white hair and a severe gaze that resembled the portrait of Andrew Jackson on the twenty-dollar bill.

Like Andrew Jackson, Landis was a divisive figure who made his share of enemies. He was a corporate lawyer, then got appointed as a judge by Theodore Roosevelt, and he issued wild rulings and engaged in wild theatrics from behind the bench. In a lot of ways, he was a contradictory figure: A corporate product who become a critic of corporations, including the monopolistic Standard Oil; a prohibitionist and a prude, wrote Sports Illustrated’s Ron Fimrite, who also swore like a sailor.

“His career,” wrote columnist Heywood Broun in the New York World, “typifies the heights to which dramatic talent may carry a man in America”—and in 1920, Kenesaw Mountain Landis was the man the owners of Major League Baseball turned to in order to clean up their sport, to “safeguard the interests of the national game of baseball.” The owners chose Landis, in part, because he had delayed a ruling in a 1915 case involving the upstart Federal League, which could have struck down the reserve clause over 50 years before Curt Flood challenged it (eventually, the Federal League settled and went out of business). The owners also chose Landis because they wanted someone who would rule with an “iron hand,” but they also presumed Landis would ultimately always be on their side.

Landis did rule with an iron hand in banning eight of the Black Sox players who had conspired to throw the World Series. He suspended Babe Ruth for violating an arcane rule about playing in postseason barnstorming games. He took on owners for stockpiling prospects on their minor-league teams and denying opportunities to players to play in the big leagues, and he banished Phillies owner William Cox for life for gambling on games.

But all of that disguised Landis’s tacit approval of baseball’s most shameful sin: In 1942, a 28-year-old maverick named Bill Veeck wanted to buy the Phillies before Cox did, and made clear that he would stock the team during wartime with players from the Negro Leagues. The day after Veeck informed Landis of his plans, the National League took control of the Phillies, and eventually sold them to Cox. There was no official rule banning black players, Landis said, but he also pushed against any effort to push baseball toward integration. He was, ultimately, doing what the owners who employed him wanted to do; he was safeguarding their interests above all.

II.

“The commissioner enjoys full disciplinary authority over his thirty-two bosses and their teams. What’s unusual about this arrangement is that he also serves at the pleasure of the thirty-two owners and carries out their wishes—except when he is fining them and taking away draft picks and damaging their reputations.”

—From Big Game, by Mark Leibovich

III.

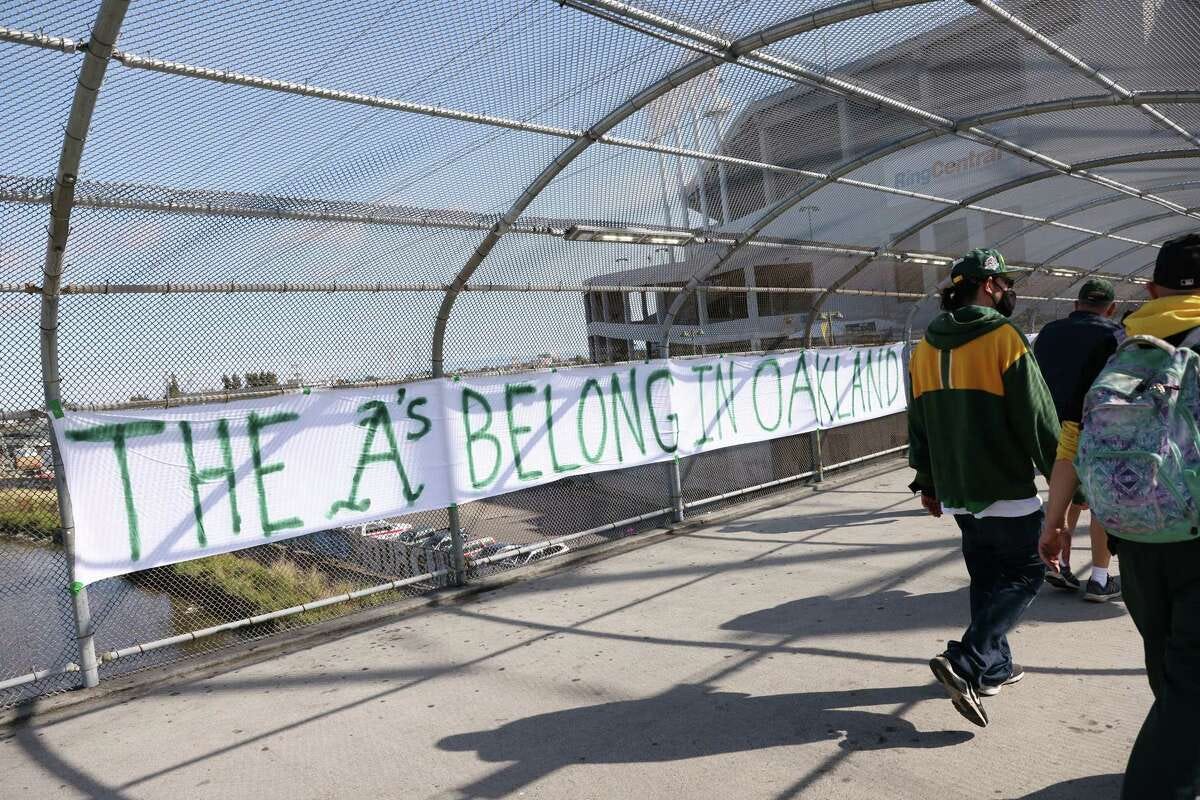

Last week, the current commissioner of baseball got onto a conference call with reporters and managed to A.) Spew several blatant lies, and B.) Insult an venerable and long-suffering fan base at its lowest moment. In the annals of commissionerly arrogance, this was an A-plus performance; it out-Goodelled Roger Goodell himself. It was the kind of thing that would have gotten Rob Manfred fired on the spot if he had a normal job in a normal workplace with normal bosses who actually cared about qualities like honesty and integrity and decency.

But this is not how it works. Not in this scenario. Rob Manfred, in this case, is a useful tool. His bosses have a problem, which is that the owner of the Oakland Athletics is a pernicious recluse who spent years dithering about where and how he wanted to build a new stadium in Oakland, and insisted he couldn’t possibly build it without public money, despite being worth billions, and refused to sell the team even when it was clear he had completely screwed over the current city government in Oakland.

"Tarnished somewhat by the move" (1995)

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics. Welcome to all new readers/subscribers, and if you like what you’re reading, please join the mailing list and share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing. (

Until the situation in Oakland was resolved, baseball could not think about expansion, and so it was Manfred’s charge to put this situation behind him for the benefit of his bosses. And in order to get this whole awful mess settled, lying and insults fit within Manfred’s job description.

This, of course, is not the first time Manfred has lied. He lies and he lies and he lies, and because of the odd structure of his position, he is able to get away with it, because this is what his bosses demand of him, and because he managed to force through some rules changes that people seem to like. “Manfred is a bad commissioner because the office of the Commissioner of Baseball is set up to create bad commissioners,” wrote SB Nation’s Graham MacAree back in 2020, but I would go beyond that—I would argue that the very idea of a sports commissioner who is beholden to his bosses in any way is completely flawed, and Manfred is just the zenith of this fucked-up structure.

And I would argue that this holds true outside of sports, including the vexing fact that the president appoints the attorney general of the United States, and the fact that judges like Kenesaw Mountain Landis—as well as Supreme Court justices—are essentially political appointees who are then expectedly to act apolitically. And I would argue, as Michael Lewis does in this excellent podcast, that it gets at a deeper problem: As we’ve lost faith in our institutions, we’ve kind of lost the thread when it comes to trusting the idea that neutral arbiters can exist at all in modern life.

IV.

By 1944, Landis had served as commissioner for two decades, and the owners, Fimrite writes, wondered if “they had created a monster.” They tried to rein him in, but it was too late—Landis was popular among the press and public for his seeming independence. Over time, Landis’s reputation has sunk, largely because he did not stand up to the owners and executives who wanted to keep baseball white, even as black soldiers were fighting overseas. He’s increasingly viewed as more of an irascile conman than a true maverick.

Later in 1944, as Landis lay in a hospital bed with heart failure, the owners extended his contract by seven years, knowing they’d be rid of him long before then. He died eight days later, at the age of 78, and even as his successor, Happy Chandler, helped usher in the era of integration in baseball, Chandler also continued to exaggerate—and even outright lie—about how he’d stood up to the owners who also served as his bosses. And it’s been that way ever since.

This newsletter is a perpetual work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Reply to this newsletter, contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please join the list and/or share it with others or consider a paid subscription.

Sweet stuff