Special Edition: Throwbacks Goes To the Super Bowl

I watched the least interesting Super Bowl in years from inside a fishbowl. Then Bad Bunny happened.

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture, and politics—and how they all bleed together.

If you like what you read, please click the button below, join the mailing list for FREE and please share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing.

And if you’ve been reading for a while, please consider joining the list of paid subscribers to unlock paid posts and allow me to expand Throwbacks’ offerings.

Here’s a link to get 20 percent off a monthly membership for your first year:

And here’s link to get 25 percent off an annual membership:

(If you cannot afford a paid subscription and would like one, send me an email and I’ll comp you one, no questions asked.)

I.

There’s this thing you realize pretty quickly if you ever get the opportunity to attend a Super Bowl in person, which is that the game isn’t really meant for you. The Super Bowl is an event that’s choreographed and optimized for television; this is true of every professional football game, but it’s especially true of the Super Bowl, which means that if you actually show up to it, you’re essentially consigned to being a historical extra.

Nobody expects a Super Bowl crowd to be raucous, and they never are, because the game is played at a neutral site and largely attended by people who care less about football and more about being seen around football. Nobody in the production truck gives a thought to the fact that you’re standing in the stadium watching some woman in a tri-cornered Patriots hat on the jumbotron, while the rest of America is buzzing over the product of some ad agency’s sativa-fueled Mad Libs experiment where Sabrina Carpenter woos a sentient potato chip. You might bear witness to the event, but you are not the focus of this event in any way, shape or form. Once the game starts, it feels like could just as well be watching the North Dakota small-school state championship.

I’ve been lucky enough to go to three Super Bowls now, including Super Bowl LX, and every time I had that same sensation of feeling excluded from the conversation. For all three, I’ve sat in the press box, and this time I sat in the press box at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California, where for some reason—even though the weather is almost always ideal—the windows don’t appear to open at all. So I was sitting there watching a football game that already felt like it was kind of on mute, except that I was watching it on mute, because I couldn’t really hear much of anything, in part because there wasn’t much to hear in the first place. The only sound I could detect was the steady buzz of the New York sportswriters sitting next to me, who mostly seemed interested in discussing prop bets and making jokes about Sam Darnold.

Anyway, you know how the game went. There were no surprises. Seattle was the superior team, and Seattle won the game. I don’t expect anyone outside of Seattle to remember any of this Super Bowl; I’m not sure if I will remember any of it. I watched one of the least interesting Super Bowl games of all time while sitting inside a virtual fishbowl at a stadium located roughly fifty miles from the city it purports to represent.

When I was walking back to the train afterward, I overheard this conversation from a pair of Seattle fans:

Fan A: Where’s Greg?

Fan B: I don’t know. He looked at me in third quarter and said, ‘This is great. We’re gonna win the Super Bowl.’ And then in the fourth quarter he said, ‘I’m bored.’ And then I think he left.

Fan A: I’ve got some DiGiornio’s back at the Airbnb.

Fan B: That’s great!

This was one of the most competitive seasons in recent memory, and so the NFL had already won, which is why maybe karma doomed them to a mismatch in the Super Bowl. In fact, the only thing we’re likely to remember from this Super Bowl is the halftime show, because it managed to lay bare the absurdity of the moment we’re currently living through.

II.

There’s a story in New York Times reporter Ken Belson’s book Every Day Is Sunday, about the Roger Goodell era of pro football, that kind of frames the absurdity of the controversy over Bad Bunny performing at the halftime show in Santa Clara. Belson paints Goodell as a gung-ho commissioner with an expansive vision that often borders on megalomania. Early in his tenure, Belson writes, Goodell framed logos of some of the biggest corporations in America and hung them on the walls of his office, because he believed the NFL should take its place alongside them.

And give Goodell credit: That’s exactly what he’s accomplished. The NFL—despite the political and cultural and scientific controversies that threatened to shrink its footprint—is now arguably the most successful single corporate entity in American life. Like every gargantuan corporation, pro football has to find a way to keep growing—to keep that (left) shark swimming. And that means broadening the NFL’s audience overseas. This is one of the primary reasons why the NFL has embraced international flag football; it’s why the NFL is playing a game in Paris next season, and why it regularly schedules games in Europe and Latin America. This is how the NFL can keep getting bigger, and this is why it made sense for the world’s most popular Spanish-speaking recording artist to play the Super Bowl halftime show. And the fact that this was somehow a controversial decision—a decision based entirely on capitalistic urges—mostly shows just how the politics of the current administration have in some ways become antithetical to capitalism itself.

III.

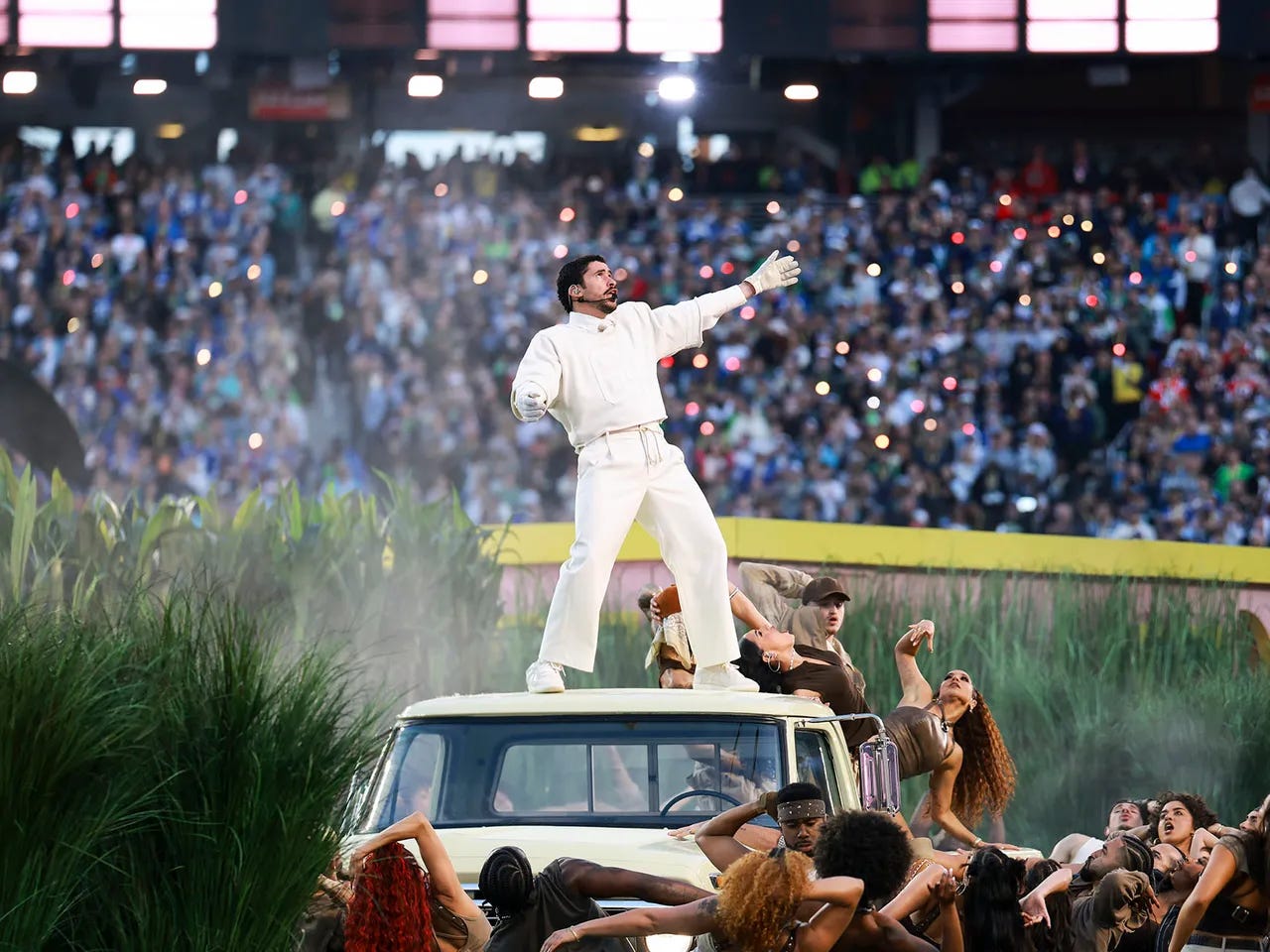

I watched the halftime show from that odd fishbowl of a press box. I couldn’t hear much of anything, and maybe that worked in my favor, because I don’t know Bad Bunny’s music, and honestly, I’m a middle-aged white guy with a soft spot for Grand Funk Railroad. Instead, I focused almost entirely on the visuals. And the first thing I noticed was how utterly washed in color the whole thing was. There were humans disguised as vegetation, and dancers in shades of khaki, and Bad Bunny himself in white from head to toe, and there were flags of Latin American countries, and everything was so saturated in shades of yellow and red and green that it felt as if we’d gone from black-and-white to color, like in The Wizard of Oz.

The second thing I noticed, and that everyone else seemed to notice as well, is that it felt so jubilant, and that it was as if somehow jubilation itself has become an act of defiance in America. This was a bad Super Bowl with terrible uniforms played in a stadium that was built in one of the least interesting stretches of the Bay Area; this has also been a year where we’ve been bombarded with horrifying images and assured by our leaders that these horrifying images are justified because everything is worse than we ever could have imagined it to be. Bad Bunny completely cut against that. He is a wildly famous artist who has become wildly famous by embracing his cultural identity, and this was the identity the NFL wanted to project, no matter the fraught nature of the current political moment.

I guess, in a strange way, you have to give Roger Goodell credit for embracing his Machiavellian expansionist interests over the fury of a president with his own unhinged expansionist interests. By the time Bad Bunny was finished, by the time he’d wended his way through a maze of mock sugar cane plants and handed a kid his Grammy, any skepticism about the moment felt as if it had been obliterated. And I’m sorry to get all idealistic on you, but to hell with it: The language barrier here was not Spanish vs. English; the language barrier here was joy vs. cynicism.

IV.

This is not to say that a Super Bowl halftime show will change much of anything at all, just as this Super Bowl itself might not change anything at all. It is easy to proclaim after Sunday that the Seahawks might blossom into the league’s next great dynasty, but I’m not sure I believe it; it is easy to proclaim that Drake Maye will now devolve into the next Tony Eason, but I’m not ready to believe that, either.

One game will most likely not change anything, but after six decades of Super Bowls, it’s become clear that the NFL knows what it wants from its big game beyond the result: It just wants that game to keep getting bigger and bigger. Someday, when this era is over, and when we break out of this fishbowl, we will look back and remember nothing about the game, and we may even forget that the halftime performer was somehow controversial. And oddly, that was the message of this Super Bowl, delivered by the NFL itself: We have no desire to be at war with a huge portion of the world, because they are customers, too.

This newsletter is a perpetual work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Respond to this newsletter, Contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please join the list and/or share it with others.

A journalist with inside information passed along this little tidbit. The NFL knew Bad Bunny was controversial -- but the league went ahead with him as the halftime headliner because Apple wanted it. Apple plans to use Bad Bunny on multiple platforms in the near future. The NFL wants Apple for future advertising on their game broadcasts, so this was purely a money play for the future. The league figures the controversy will quickly go away, because Americans have notoriously short memories.

You hit it dead center of the uprights as usual. Kinda glad I didn’t go now.