This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics, and everything in-between.

If you like what you read, please click the button below, join the mailing list for FREE and please share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing.

And if you’ve been reading for a while, please consider a paid subscription to unlock certain posts and help keep this thing going—you’ll also get full access to the historical archive of over 200 articles. (Click here and you’ll get 20 percent off either a monthly or annual subscription for the first year.

(If your subscription is up for renewal, just shoot me an email and I’ll figure out a way to get you that discount, as well. If you cannot afford a paid subscription and would like one, send me an email and I’ll comp you one, no questions asked.)

I.

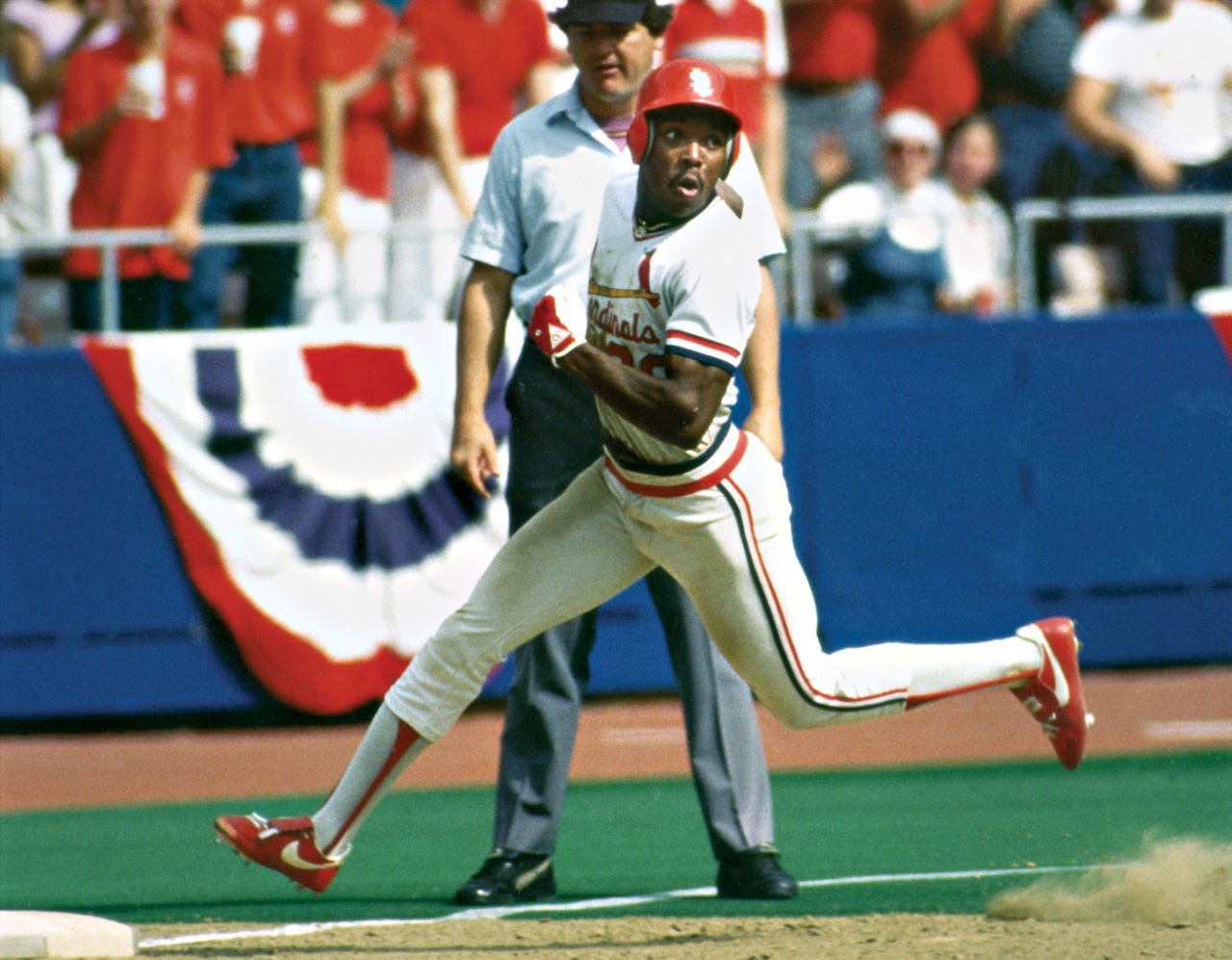

One evening in July of 1985, in the fourth inning of a game against the San Diego Padres, the St. Louis Cardinals’ leadoff batter, Vince Coleman, bunted for a base hit. The next hitter, Willie McGee, drew a walk, and then Coleman and McGee pulled off their second double steal of the game, and when a rushed throw to third from catcher Terry Kennedy trickled into right field, Coleman made a beeline for home plate and scored.

That night, in a 6-0 win over the Padres, the Cardinals stole eight bases—three each by Coleman and McGee—and the Padres, rattled by the sheer scope of what they were witnessing, committed five errors. Over the course of the 1985 season, Coleman would steal a league-leading 110 bases; the Cardinals would win 100 games and come one controversial call away from winning the World Series, while also becoming the first team to steal over 300 bases and hit fewer than 100 home runs.

By the summer of 1985, it was clear that the stolen base had become the essence of modern baseball. Rickey Henderson—building off the influence of Lou Brock—had commenced the era in 1979. In 1981, Tim Raines had joined Henderson as a prolific base stealer who altered the trajectory of a game. And now there were Coleman and the Cardinals, who had built their entire offense around the notion that speed could disrupt the rhythm of an often staid and static sport. The very presence of charismatic and fearless dudes like Henderson and Coleman and Raines—who stole a combined 260 bases over the course of the summer of ‘85—ratcheted up the tension of an ordinary July day during an ordinary Thursday game against the San Diego Padres.

This was the baseball I grew up with; this, I think, was the reason that the sport felt so alive at that moment, in ways it often hasn’t in the decades since. And it may be too late for baseball to ever regain the kind of cultural cache it had in the 1980s, but at the very least, it feels as if the last dirt has been tossed on the grave of the Moneyball era, because the stolen base is back.

II.

Last Sunday in Milwaukee, a second baseman named Brice Turang led off with a base hit for the Brewers against the Oakland1 Athletics. Turang stole second, and then he and outfielder Christian Yelich pulled off a double steal, and Turang scored on a subsquent throwing error, and then Rhys Hoskins drove in Turang with a single, and then Hoskins and William Contreras pulled off another double steal, and then Hoskins scored on a balk, and then outfielder Sal Frelick walked and stole second, and then Hoskins scored on another throwing error.

If you lost count, that is six stolen bases in a single inning, the first time that had happened since at least the onset of the divisional era in 1969. By the end of the night, the Brewers had stolen a team record nine bases. Over the course of the first three weeks of the season, according to CBS Sports writer Mike Axisa, teams are attempting to steal bases more than they did even in the past couple of seasons, when steal attempts had already begun to rise—thanks in part to new rules encouraging basestealing, and thanks in part to a shift in strategy. And those numbers may only grow further, Axisa writes:

In 2023 and 2024, the full season attempt rate was higher than the first three weeks, which makes sense. It's cold early in the season, often rainy, which means a soft infield that isn't great for running. Once the weather warms up, teams run even more. We could have an 8% attempt rate in 2025!

That is Axisa’s exclamation point, not mine. But, as someone who has often been disappointed by baseball’s stubborn conservatism, I share a tentative sense of excitement, even if I am still skeptical enough not to share his punctuation.

III.

The problem with baseball is that it has so often defaulted toward boredom. For much of the 21st century, in the wake of an era when an illusory spike in home runs wound up tarnishing the reputation of the sport, the smart thing to do and the interesting thing to do appeared to be at odds with each other. Moneyball—which condemned stolen bases as a needless risk—was interesting when it was used as an equalizer by teams who had a deficiency of talent, but when everybody started doing it, the game became flat. Nothing moved. You walked and you waited, and this was baseball at its worst, a static sport that seemed designed to put you to sleep.

But you can actively sense the change now. The games feel different; the angles themselves seem to have tightened. The implementation of a pitch clock sped things up, but now it feels like the pace itself is speeding up all over, and it is not just stolen bases: There is more room for spectacular power-plus-speed athletes like Cincinnati’s Elly de la Cruz to play with the kind of abandon that might have been neutered during the Moneyball era. The Rays just called up Chandler Simpson, who stole 100 bases in the minors last year. The Pirates’ O’Neil Cruz stole 22 bases all of last season and leads the league with 10 already this season; in San Diego, outfielder Fernando Tatis has hit eight home runs and seven stolen bases. My adopted team, the San Francisco Giants, have a Korean center fielder named Jung Hoo Lee, who has become a fan favorite not because he steals a tremendous amount of bases, but because he moves quick and economically has a compact swing patterned after Ichiro Suzuki.

I’m not entirely sure how to explain it, except to say that the game just moves more smoothly right now. There is more drama from moment to moment because it is more disruptive than it has been since the 1980s. And maybe it’s just because the status quo in this country feels so oppressively weighted, but it also feels like a good time for baseball to rediscover its disruptive soul. The outside world is heavy—and it seems inevitable that this will be a summer marked by rebellion and protest—but at least baseball is starting to feel lighter and more fluid than it has in four decades, when the Cardinals were running with complete and utter abandon, and when Rickey Henderson and Tim Raines and Vince Coleman were determined to shift the vibe of baseball itself. And I only hope that it keeps moving in that direction instead of once again bogging down under its own weight, because, as Coleman told a reporter back in 1985, baseball is best when it rebels against its own snoozy default status.

“I don’t think like a lot of guys who run track,” Coleman said. “They always just run for time. That’s boring. If I’m running, I’m running for excitement.”

In case you’re tempted to celebrate Rob Manfred for any of these rules changes, let us remember that no one has done more at the same time to destroy baseball’s reputation off the field, and to enable some of the worst owners in sports.

This newsletter is very much a work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please subscribe and/or share it with others.

Worst owners in sport by leaps and bounds! Well said sir! ⚾️

Yesterday watched Red Sox player, Duran, hit a triple then steal home. It was wild. Moneyball was beer league slow pitch softball. Strike out or home run. The Athletics won no titles.