Whatever happened to baseball?

A sport without a (television) home feels increasingly reflective of a splintered country.

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics, and everything in-between.

If you like what you read, please click the button below, join the mailing list for FREE and please share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing.

And if you’ve been reading for a while, please consider a paid subscription to unlock certain posts and help keep this thing going—you’ll also get full access to the historical archive of over 200 articles. (Click here and you’ll get 20 percent off either a monthly or annual subscription for the first year.

(If your subscription is up for renewal, just shoot me an email and I’ll figure out a way to get you that discount, as well. If you cannot afford a subscription and would like one, send me an email and I’ll comp you one, no questions asked.)

I.

This is a newsletter about baseball that begins with a photo of a football player. That football player’s name is Trevon Diggs. Perhaps you have heard of him; perhaps you have not. Which is exactly my point.

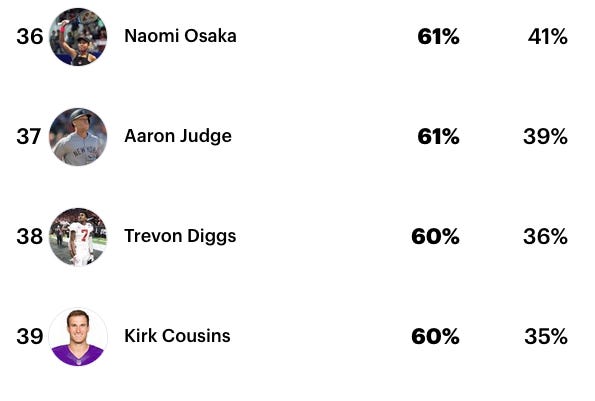

In 2020, the Dallas Cowboys drafted Trevon Diggs in the second round of the NFL draft. Diggs, a cornerback, made the Pro Bowl in 2021 and 2022; he has, over the course of the past five years, been one of the better defensive players on one of the most popular football teams in America, but he is certainly not a household name. In 2024, Diggs played 11 games and then sat out the rest of the season due to knee surgery, and I promise there is a reason I am reciting information from Diggs’ Wikipedia page, as it relates to this YouGov poll of the most popular contemporary athletes in American in the fourth quarter of 2024.

I know sometimes these kinds of polls produce strange and unreliable results. But still, according to that YouGov survey, Trevon Diggs—a dude I had certainly heard of through sheer osmosis, but had honestly never thought much about—is equally as famous and recognizable as the most well-known baseball player in America. And assuming this poll is at least reasonably accurate, it doesn’t surprise me at all.

II.

One of my rites of spring involves combing online fantasy baseball rankings and wondering how it is possible, year after year, that I continue to know so little about baseball. I am in very low-stakes league with a group of my college friends, and part of the reason I enjoy it is that it force me to engage with baseball at-large, and part of the reason I also enjoy it is that it almost deliberately low-tech: We conduct our draft offline via email, and it takes many days (or weeks) to complete, and people (including me) often attempt to pick players in the 18th round who were one of our five keepers from the previous season.

The other day, I used a third-round pick to choose a Cincinnati Reds infielder named Matt McLain; if it turns out Matt McLain is in fact an elaborate AI hoax, I would not be the least bit surprised. This is how our draft goes: Everyone in my league—many of them sportswriters or former sportswriters—regularly admits that they have no idea what they’re doing, because who does have any idea what they’re doing anymore when it comes to drafting a middle infielder from the Rays? Yes, we are Giants fans or Mets fans or Pirates fans or Phillies fans. But baseball fans? That is another thing altogether.

Baseball is such a splintered and regional sport these days that it takes a concerted effort to keep up on a holistic level. I imagine I am a typical baseball viewer—not only in the fact that I am a rapidly aging white dude, but also because I watch my team play other teams, and then I do not pay much attention to those teams outside of my own narrow regional purview. I do not particularly care about watching a random Sunday night baseball game between, say, a pair of American League Central teams, and I am not alone. In fact, even after a small bump in viewership last season, the national audience for baseball has dissipated to the point that even the most prominent sports network in America feels no great need to be in the business of baseball anymore.

III.

Last week, the president of ESPN, Jimmy Pitaro, reportedly met with the commissioner of Major League Baseball, Rob Manfred, and told him that ESPN wasn’t interested in continuing their broadcast relationship unless Manfred was willing to take less money. Manfred, dishonest broker that he is, attempted to frame the break-up as mutual, and decried the apparent neglect by ESPN, which he claims did not hype up the sport enough outside of its own broadcasts.

This is a completely silly contention, and that silliness is reflected in this episode of Pablo Torre’s always excellent podcast, in which former ESPN executive John Skipper and former Miami Marlins executive David Samson argue over whether ESPN somehow degraded baseball by refusing to cover it as much as they should have. Skipper says that baseball executives complained to him about their coverage more than any other sport; Samson, an otherwise smart and engaging dude, puts much of the onus on the network while admitting that baseball was largely concerned about being “considered a second-class sport.”

As a former employee of ESPN, I have no great love for ESPN (though I did respect John Skipper in my limited dealings with him). But I think it’s patently absurd to claim that baseball’s cultural decline is ESPN’s fault in any way. Baseball did a good job of digging its own hole over the course of the past three decades, with or without ESPN. They ignored their fans and refused to embrace modernity for decades, and they continue to broaden the gap between the haves and have-nots without any regard for how it might affect their perception.

And sure, there are also some complex sports-business related reasons behind the breakup between ESPN and MLB, and you can learn more about them by reading this Wall Street Journal article, or by reading this Andrew Marchand piece in The Athletic. As Marchand writes, Manfred’s attempts to speed up the game have been an unquestioned success, and people are still attending games in person, because baseball parks are generally very nice places now. But at the same time, the collapse of regional television networks in the streaming era has meant that the disparity between large-market teams and small-market teams is bigger than ever, and the large-market teams have no interest in propping up the small-market teams by embracing a national television package, which is really the only way to make baseball relevant on a national scale again.

“The problem is that today’s media market looks vastly different to small-market teams like the Milwaukee Brewers and Pittsburgh Pirates than it does to economic juggernauts like the Dodgers and New York Yankees,” the Wall Street Journal wrote. “The more difficult task for Manfred will be convincing teams like the Yankees, Dodgers, Boston Red Sox and Chicago Cubs that giving up control of their local media for the greater good will ultimately benefit them, too.”

IV.

That Wall Street Journal quote tells me that baseball is in deep trouble, and so, too, is Manfred’s legacy. (I’d like to think consensus-building is a responsibility that generally falls on the commissioner, who recently allowed his most deadbeat owner to move his franchise to a minor-league baseball stadium in Sacramento for several years rather than sell the team, thereby cheapening the entire sport.) It tells me that baseball is scrambling to find a place in a modern society that consumes the sport far differently than it has in the past. It tells me that the owners Manfred works for still seem to think that baseball isn’t a second-class sport, despite the fact that ESPN just walked away from it. (See below, and note that basketball has a far younger audience that is almost comically overengaged on social media, whereas baseball feels absent from the daily conversation.)

In that unsettled environment, it is no surprise that baseball owners’ interests are fractured, and that the bigger franchises are more interested in looking out for their own self-preservation than in looking out for the greater good. (As we’re learning, this is what rich people tend to do when the going gets tough—grab as much as they can for themselves before the system collapses.) The problem is that professional sports work best as a collective; they do not work if there is no consensus to embrace the greater good over the profit motive. Baseball may have improved its on-field product, but off the field, it feels as splintered as ever. Its power brokers appear marooned in a bygone past, clinging to a level of rampant selfishness that poses an existential threat to its future. I guess when you look at it that way, maybe baseball is still the American pastime.

This newsletter is very much a work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please subscribe and/or share it with others.

Great piece. I personally am a baseball enjoyer at all levels and am willing to watch an AL Central clash on Sunday Night Baseball, but I know that's not the same for most who (like you) are regional fans of a primarily regional sport. I'm curious about your thoughts/personal preference on baseball media. The NBA constantly points to the popularity of their league on alternative forms of media (outside of traditional consumption). Do you personally have any appetite for clips, newsletters, podcasts, or alternative forms of media that break down a game of baseball? A related question, do you think fans want, or even care about, engaging national baseball content? A topic I continue to be fascinated by.

I love baseball. I grew up playing it and watching the Braves. The regular season does not matter from a broadcast perspective and ESPN did not have the rights to the playoffs. Do we need 162 games to decide the playoff lineup? I don’t know, but much of the regular season is just not interesting.