Why We Need the Knuckleball (1985)

As culture grows stale, the most artistic pitch in baseball feels more important than ever.

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics, and everything in-between.

If you like what you read, please click the button below, join the mailing list for FREE and please share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing.

And if you’ve been reading for a while, please consider a paid subscription to unlock certain posts and help keep this thing going—you’ll also get full access to the historical archive of over 250 articles. (Click here and you’ll get 20 percent off either a monthly or annual subscription for the first year.)

(If your subscription is up for renewal, just shoot me an email and I’ll figure out a way to get you that discount, as well. If you cannot afford a paid subscription and would like one, send me an email and I’ll comp you one, no questions asked.)

I.

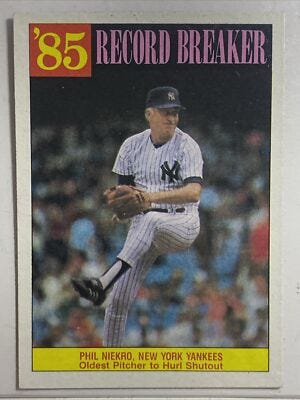

That is a photo of legendary knuckleball pitcher Phil Niekro at roughly the age of 46, and beyond the fact that Niekro already looked 65 (and then seemingly did not age at all for the last four decades of his life), it is a reminder of just how wonderfully strange baseball used to be. In 1984, at the age of 45, while looking like a refugee from The Villages, Niekro was an All-Star pitcher with the New York Yankees; and even in 1985, as his signature pitch finally began to give way to the gravity of aging, he threw seven complete games. While in his forties, Phil Niekro won 121 games, which is more than all but six active Major League pitchers have won over the course of their entire careers.

The knuckleball liberated both Phil Niekro and his brother Joe from following in their father’s footsteps and becoming coal miners in southern Ohio. This underlying sense of desperation forms the story of nearly every knuckleballer: They often fail to make it by conventional means, so they turn to the Zen of a pitch that no one fully understands. The knuckleball inverts every expectation inherent to sports, which are driven by archetypes of power and strength. If you throw a knuckleball at full speed, it doesn’t work, because it isn’t supposed to spin at all. It’s dynamics are not easily explained by science; its complexity and fickleness makes a lot of scouts and managers very uncomfortable. It requires patience and time to learn, and even its most skilled practitioners find that it comes and goes in an instant. It is a kind of Rohrshach test: The people who distrust it or dismiss it as a gimmick are usually the same people who are unwilling to wait patiently in traffic, or to accept the fact that certain things in life are inexplicable. The people who throw it treat it more like art than commerce, which is why it is no coincidence that one of the best knuckleball pitchers in recent years, R.A. Dickey, was an English literature major in college.

For decades, a handful of knuckleballers bounced from team to team or became a beloved franchise anchor like Tim Wakefield in Boston; it was rare, but it endured. But as of right now, there are no full-time knuckleballers in Major League Baseball1, and at a time when the culture at large has devolved into a crass attention-seeking algorithm, its disappearance feels like a metaphor: The knuckleball is an art-house director marooned in a Marvel universe.

II.

“Back in 2000,” writes culture critic

, “80% of movie revenues came from original ideas. But this has now totally flip-flopped.“Today 80% of the movie business is built on old ideas—remakes, and spin-offs, and various other brand extensions. And we went from 80% new to 80% old in just a few years.”

The same thing is happening in music, as Gioia notes; people have started retreating into listening to old music, in part because this is where algorithms and AI direct them to go. And baseball, drowning in numbers and analytics, is fighting the same battle, especially when it comes to pitching. “The focus on velocity, ‘stuff,’ and max-effort pitching—have caused a noticeable and detrimental impact on the quality of the game on the field,” noted a recent report by Major League Baseball. “Such trends are inherently counter to contact-oriented approaches that create more balls in play and result in the type of on-field action that fans want to see.”

Or, as former Braves pitching coach Leo Mazzone told The Atlantic’s Michael Powell, “The game now is all about speed. And it’s all bullshit.” And yet there is hope; Gioia holds the belief that eventually, these trends will begin to reverse themselves, and that maybe a culture driven by speed and maximalism and by the tyranny of the algorithm will begin to feel so empty that people will soon demand something more interesting. In some ways, it might already be happening.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Throwbacks: A Newsletter About Sports History and Culture to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.