"That Man is Dangerous" (November, 1978)

The night two American pastimes--football and political violence--collided.

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics, and everything in-between.

If you like what you read, please click the button below, join the mailing list for FREE and please share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing.

And if you’ve been reading for a while, please consider a paid subscription to unlock certain posts and help keep this thing going—you’ll also get full access to the historical archive of over 250 articles. (Click here and you’ll get 20 percent off either a monthly or annual subscription for the first year.)

(If your subscription is up for renewal, just shoot me an email and I’ll figure out a way to get you that discount, as well. If you cannot afford a paid subscription and would like one, send me an email and I’ll comp you one, no questions asked.)

Note: In light of the fact that my nearly decade-old MacBook chose to cast itself into an eternal black hole without warning on Monday, and in light of this baffling headline…

…I figured now might be a good time to re-run this piece from a few years back.

I.

On November 27, 1978, precisely fifteen years after the National Football League insisted upon playing a full slate of games in the wake of an American tragedy, they played a football game in San Francisco in the wake of another American tragedy. No one seemed certain why the game needed to go on, except that postponing it would have caused logistical headaches for the league’s schedulers and for a major television network. And so on a Monday night at Candlestick Park, the San Francisco 49ers played the Pittsburgh Steelers, with a few brief acknowledgements from Howard Cosell and others that the entire city was mired in a deep state of shock.

The Steelers were a very good football team that season; the 49ers were an unbelievably bad football team. In a fit of desperation, the 49ers’ historically incompetent general manager, Joe Thomas, had traded a first-round pick for an aging running back with bad knees, a San Francisco native named Orenthal James Simpson. The 49ers were 1-11 heading into the Steeler game, and if a football team can serve as the metaphor for its city, this was it: The 49ers were utterly bereft. So, too, were the citizens of San Francisco, who, over the course of roughly ten days, had watched the Jonestown tragedy unfold, then on the morning of the Steeler game, had been forced to process another deep shock: City supervisor Harvey Milk and mayor George Moscone had been murdered by former city supervisor Dan White.

It was the darkest moment in a dark era for the city, an era of serial killings and cults that author David Talbot would later dub the Season of the Witch. San Francisco, in the wake of the Sixties and the Summer of Love, became associated with the dark aftermath of the social changes the Sixties had wrought. Serial killers. Cults. Crime. The atmosphere in both San Francisco and in many urban centers was dark and depressing; the city, and the nation, felt as if it had lost all sense of control. Here is how one local politician described the political atmosphere, both in San Francisco and beyond:

II.

There are several moments in Randy Shilts’ remarkable biography of Harvey Milk in which Shilts recounts Milk telling friends and colleagues that he would be dead soon. Milk knew what was coming; he understood that the principles he was advocating for—true equality for gay people—would not be tolerated by a certain conservative segment of the city, and of the country. He knew that people looked at him, an openly gay politician in an openly gay neighborhood, and saw a rapidly changing culture, and that change frightened them. Among those frightened people were Dan White, an Irish Catholic conservative and ex-cop who clashed frequently with Milk.

“That man is dangerous,” Milk had told people about White. In a tape-recorded statement nine days before his death, Milk said, “I fully realize that a person who stands for what I stand for, an activist…becomes the target for a person who is insecure, terrified, afraid or very disturbed with themselves.”

In the days leading up to November 27th, White resigned his position on the city’s board of supervisors, then tried to reverse his resignation. When Moscone refused to re-appoint him and Milk supported the decision, White climbed through a first-floor window of City Hall to dodge the metal detectors and murdered both Moscone and Milk in cold blood.

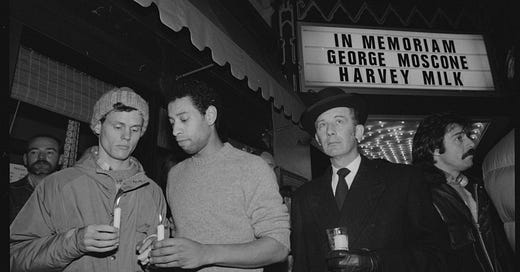

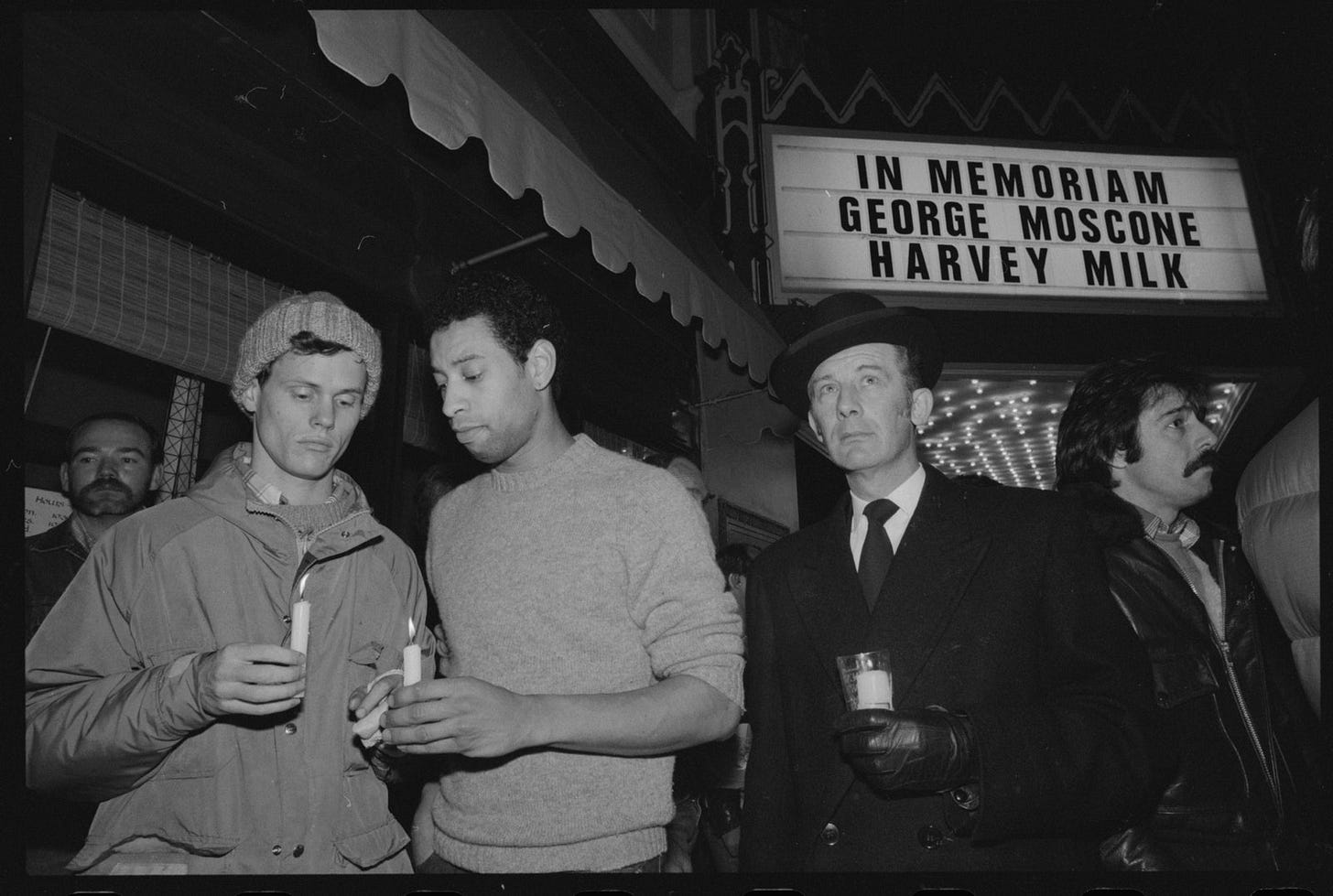

In the midst of its shock, San Francisco officials requested that the NFL postpone the 49ers-Steelers game for 24 hours to allow the city to catch its breath. The NFL refused, saying it was too late. And so the game went on that night. At the same time, in the predominantly gay Castro neighborhood, where Harvey Milk had become an iconic figure--as he eventually would become around the country, and around the world--some forty thousand people gathered, lit candles, and filled the streets for miles. And yet many of the city’s more conservative elements—including much of the police force—celebrated the death of two liberal politicians, shared tasteless jokes about the shooting of Milk, and began targeting gays for violent enforcement efforts. When a bystander asked why police officers had pulled five men from the entrance of a gay bar and started beating on them with nightsticks, the officer said, “Look, it’s easier to grab fruits.”1

The Steelers beat the 49ers that night, 24-7. After a trial that became a landmark for dubious defense strategies, Dan White was convicted of manslaughter instead of first-degree murder, served five years of a seven-year sentence. He committed suicide in 1985.

The 49ers finished the season 2-14. The Steelers went 14-2 and won the Super Bowl. An utterly meaningless football game had gone on, even if what it came to symbolize was that, fifteen years after the JFK assassination, America had essentially normalized political violence.

“It was a good thing (the NFL) stood up like this. Cancel the Monday Night Football game and everybody would have said that something was wrong,” wrote acerbic New York columnist Jimmy Breslin. “When I got up the next day, I saw in the paper a story about the gays in San Francisco who paraded with candles in memory of Harvey Milk. But this was to be expected. This was only the first gay politician to get killed in office. As time passes, you’ll see the gays get used to this sort of thing. Then maybe on the night of the killing they’ll be cheering for a football team just like all the straight people.”

This newsletter is a perpetual work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Respond to this newsletter, contact me at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please join the list and/or share it with others.

More than four decades after San Francisco became the city most closely associated with the gay rights movement—thanks in large part to the presence of Harvey Milk—the disinformation campaign about another case of political violence centered around an entirely false “rumor” about a gay tryst, in an attempt to distract from the perpetrator’s extreme views.

Trump would pardon White.