Spy Games (1976)

Barry Switzer, Michigan, and a moment of American excess.

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics, and everything in-between. Welcome to all new readers/subscribers, and if you like what you’re reading, please join the mailing list and share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing. (It’s still FREE to join the list: Just click “None” on the “subscribe now” page.) The best way you can help out is by spreading the word and sharing with others. I have set up payment tiers, if you wish to chip in and allow me the time to do a little more research on on these posts. You’ll get full access to the archive of more than 100 previous posts, as well.

I.

Of all the preposterous scandals in the history of college football, my favorite might be the one involving Barry Switzer and a lie-detector test. This was back in the 1970s, when college football in the Southwest was a thicket of amorality, and when pretty much every major program in the region was employing novel Nixonian methods for ratfucking their opponents.

In 1972, when Switzer was an assistant coach at Oklahoma, a friend of Oklahoma’s defensive coordinator dressed up as a construction worker and watched Texas practice. He warned that Texas might line up for a quick-kick punt on third down. They did just that, and Oklahoma blocked it, and went on to win 27-0. And four years later, after the Oklahoma spy got a little loose-lipped after a few drinks with a Texas booster, word got back to Darrell Royal.

This was right before the 1976 game between Texas and Oklahoma. By then, Switzer was Oklahoma’s head coach, and had already been put on probation for recruiting violations. Switzer had also ripped off Royal’s wishbone offense and rode it to back-to-back national titles in 1974 and 1975. And so when the spygate story broke, Royal, in a fit of pique, challenged Switzer, one of his assistants, and the alleged spy—an oilman (who else?) named Lonnie Williams—ten thousand dollars each to the charity of their choice to take a lie-detector test about the incident.

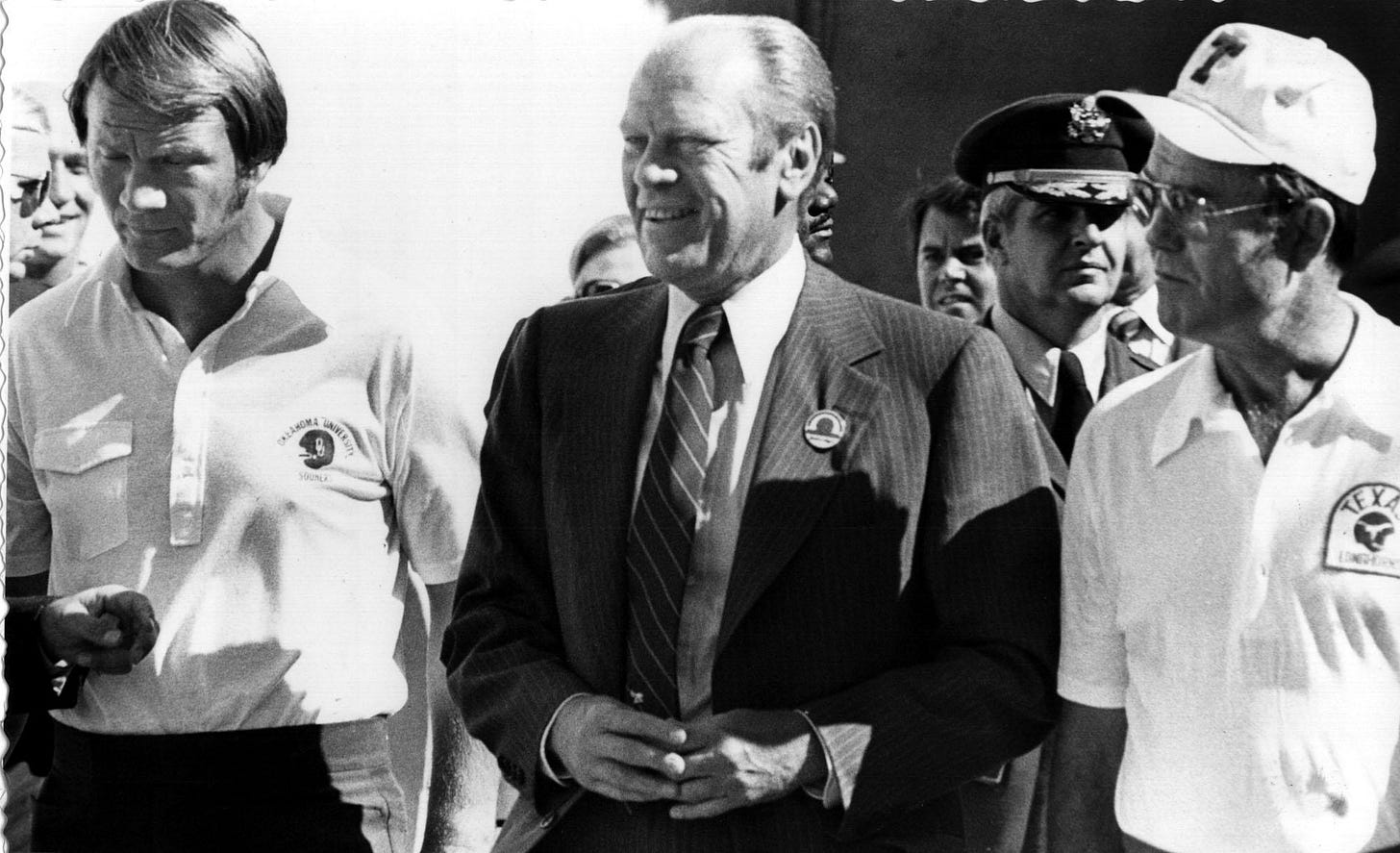

Switzer scoffed at the offer. He said he’d never spied on Texas while serving as Oklahoma’s head coach, which was true, because he was an assistant coach when it happened. Switzer was a natural-born scofflaw; he was still inside Royal’s head on gameday in 1976, when the president of the United States, Gerald Ford, awkwardly escorted a pair of feuding coaches onto the field for the coin toss. (The game ended, fittingly enough, in an unsightly 6-6 tie.)

“Why, those sorry bastards,” Royal said. “I don’t trust them on anything.”

II.

When you hear stories like this, it is hard not to view college football as an eminently absurd pastime, overseen by a feckless organization with no real power and driven by irrational levels of animosity and competitiveness and naked greed. And this is where we find ourselves, once again, in 2023, at the University of Michigan, of all places, where an ex-Marine with the Pynchon name of Connor Stalions was apparently the ringleader of an elaborately stupid spying scheme that involved buying tickets on StubHub under his real name—which apparently actually is Connor Stalions—so he could film opponents, and then surreptitiously skulking the sidelines of a Mid-American Conference program led by a coach who was once mistakenly believed to have posed naked with a dead shark.

What’s most remarkable about this scandal is not just that it’s so dumb; it’s that it’s utterly pointless. There are many ways to spy on an opponent that are firmly within the rules; one of the few things you cannot do is send advance scouts to film a team’s games. Why you would possibly need to do this in an era when literally everything is televised? How would it be more helpful to hire some amateurs to record from afar with their IPhones? And even if you were going to do it, how hard would it be to not have one of your own staffers avoid purchasing tickets under his own name, and avoid posting up on the opposing sideline like an ignoble Zelig?

(Michigan’s defense now seems to be that everyone was doing it, which is not only inaccurate, given that Michigan took it further than everyone else, but demogagic, given that this is how powerful entities often justify their own lawlessness.)

“Michigan is going to get caught for stealing signs,” wrote Steven Godfrey in the Washington Post, “because it is incredibly, hilariously bad at cheating.”

III.

This kind of blatant cheating happened quite often in the 1970s and 1980s, when schools would blantantly hand out cash and buy recruits Trans-Ams and operate on such a surface level that even the NCAA’s perpetually weak enforcement arm proved capable of catching them in the act (at least until SMU became the sacrificial lamb and inspired at least one thinly veiled screenplay, in case Matthew McConaughey happens to be reading this).

But these days, it does kind of feel like a metaphor for the moment this sport finds itself in, when the very structure of college football has been disrupted by the search for a bigger payoff, and when no one in a place of power seems to care very much how that overt avarice is perceived by the public. “Connor Stalions Is the Inevitable Product of an Excessive System,” wrote Pat Forde of Sports lllustrated, a system in which a seemingly impervious institution like the Pac-12 can simply dissolve into history under the weight of television money.

But I wonder if maybe it goes further than that. I tend to believe that college football is so uniquely American that it cannot help but reflect the arc of American culture, from Switzer adopting Nixonian tactics in the 1970s to SMU embodying the excesses of the 1980s to right now, at a moment when a 31-year-old crypto con artist appears to have so thoroughly fleeced people out of billions of dollars that it only takes four hours for a jury to convict him on all charges.

“He thought the rules did not apply to him,” a prosecutor told that jury. “He thought that he could get away with it.”

So it is in college football, and so it is in Silicon Valley, and so it is in America, where Michigan fans who spent years clinging to an elitist sense of moral virtue1 are now defending a scheme that’s the equivalent of a Scooby-Doo movie directed by Steven Soderbergh—and where we are a year away from deciding whether a man who was so incredibly, hilariously bad at cheating that he got caught over and over again somehow deserves another chance to become the leader of the free world. Maybe someday, this excessive moment in America will seem eminently absurd, too, but it sure as hell doesn’t feel that way right now.

This newsletter is a perpetual work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Reply directly to this newsletter, contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please join the list and/or share it with others or consider a paid subscription.