From the Archives: A "Meaningless" Bowl Game That Meant Everything (1962)

Why Bowls Matter, Even When They Don't.

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture, and politics—and how they all bleed together.

If you like what you read, please click the button below, join the mailing list for FREE and please share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing.

And if you’ve been reading for a while, please consider joining the list of paid subscribers to unlock paid posts and allow me to expand Throwbacks’ offerings.

(If you cannot afford a paid subscription and would like one, send me an email and I’ll comp you one, no questions asked.)

i.

Amid all the talk about how college football bowl games have become meaningless, I have some admittedly contrarian thoughts:

A.) Weren’t the vast majority of college football bowl games already meaningless to most viewers? Hasn’t Dave Barry spent every December since the 1980s crafting excellent jokes about the Tongue Depressor Bowl?

B.) Aren’t most sporting events ultimately devoid of meaning? There are 16 NFL games next weekend, and most of them will mean absolutely nothing. The vast majority of the NBA season is so meaningless that the NBA has attempted to attach meaning to it by initiating an equally meaningless tournament. In baseball, teams are often eliminated from playoff contention by the Fourth of July.

Does that mean these meaningless games shouldn’t be played at all?

C.) Why are we so fearful of meaningless in the first place? Is it tied into the militaristic zero-sum era we’re living through? I know the obvious answer is that the College Football Playoff has altered the paradigm, but do bowl games also feel less meaningful now because we now see them for what they’ve always been: Kitschy corporate products designed to sell pop-tarts and weed eaters? Why does this specific kind of empty commercialism inspire such nihilism, especially at Christmastime, when empty commercialism is all around us?

D.) Despite that meaninglessness, don’t bowl games further the narrative of the programs involved, often generating momentum (or stunting it) for future seasons? Aren’t they ultimately an opportunity to put a bow on a season, or a college career? Don’t they often evoke emotion in their participants and their respective fan bases?

E.) And so don’t these bowl games sometimes wind up meaning more than we might realize? (Boise State vs. Oklahoma was a “meaningless” bowl game until it wasn’t.)

With that in mind, here’s a deep cut from the Throwbacks archives that proves even a “meaningless” bowl game can be freighted with, well, actual meaning.

I.

By an accident of geography, I spent the first two decades of my life immersing myself in the mythology of Penn State football. At the time, it felt like a noble place for a sports-addled kid to direct his obsessions. In the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Joe Paterno was considered the one of the few ethical voices in college football. But then I grew up, and then life got complicated. In 2011, in a matter of days, a dark and ugly secret emerged from a town that had so long attempted to shield itself from the darkness and the ugliness of humanity that it referred to itself as “Happy Valley.” Except if you were paying closer attention—if I were paying closer attention—we would have realized those complications were there all along.

II.

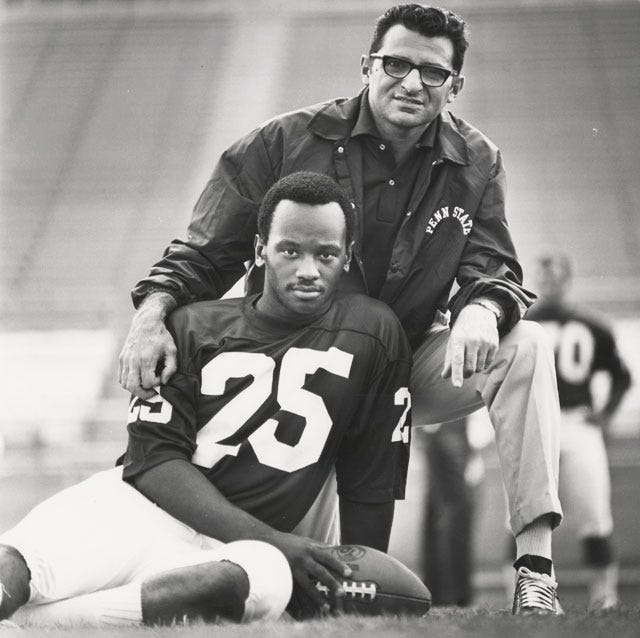

Take another look at the picture up above. That’s the 1962 Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, Penn State versus Florida, played 63 years ago this week, which, in the grand scheme of things, is not very long ago at all. That’s Dave Robinson on the left, Penn State’s star defensive end and one of the best players in the country, a future Pro Football Hall of Famer with the Green Bay Packers. And that, on the right, on the helmet of a Florida football player, is the confederate flag.

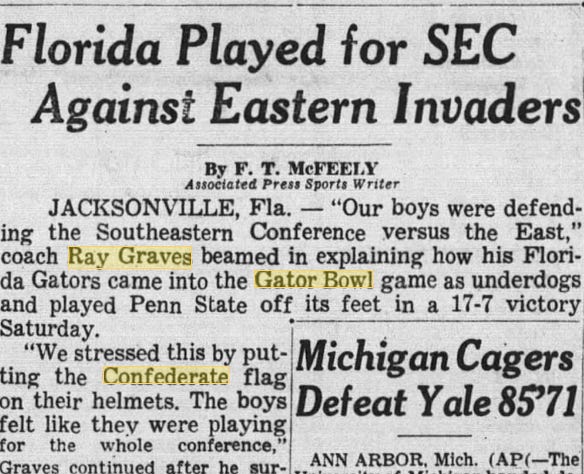

Those flags were added to Florida’s helmets especially for this game, replacing the Gators’ traditional block numbers. They were a way of hyping up an otherwise meaningless bowl game, one in which Penn State was heavily favored but had little motivation to win, and one in which Florida, under coach Ray Graves, had decided to motivate his 6-4 team by playing up the regional (North versus South) aspect of this game—which of course was an unsubtle way of playing up the racial aspect of this game, since Penn State’s program was desegregated and Florida’s was not. Graves framed the criticism of his team as akin to criticism of the south itself. Before kickoff, the Florida marching band took the field playing Dixie and waving a massive confederate flag.

In late 1962, the burgeoning Civil Rights movement had begun to gain momentum. Three months before this game, James Meredith became the first Black student to attend the University of Mississippi, sparking a riot on campus; six months after this game, Alabama Governor George Wallace would take his stand in the schoolhouse door at the University of Alabama to block a pair of Black students from registering. Southern schools felt increasing pressure to integrate both their universities and their football programs, and the game itself, author and professor Derrick E. White notes, occurred on the eve of the centennial of the Civil War.

Florida won the game 17-7. The Gators were “angry young men,” wrote author and chronicler of Penn State football Ridge Riley. Graves, Florida’s coach, had succeeded in framing this as “a contest between the South’s racial past and its future,” White wrote. “And on this day it seemed that the past won.”

III.

There is a well-known and apocryphal story about Penn State’s enduring mythology that I may have unwittingly contributed to, when I profiled a former Penn State player named Wally Triplett for the university’s alumni magazine. The story goes that Penn State’s 1947 football team, led by Triplett and another Black player, Dennie Hoggard, refused to play a bowl game in the south without bringing its Black players along with them. The story goes that Penn State’s captain, Steve Suhey, declared, “We are Penn State…it’s all or none.”

All of this is almost certainly true. What is not true is that this is how the university’s signature chant became “We Are…Penn State.” (As the late Penn State football historian Lou Prato wrote, it was, in fact, invented by cheerleaders in the 1970s.) But I understand that people want to simplify stories like these; people want to cling to mythology to make themselves feel good about the progress society has made. I believe the bond Triplett had with his white football teammates was real, and deep, and years later he still had real, deep emotions about the mythology of the “We Are…Penn State” chant reflected that legitimate friendships he formed.

But here is what else I remember about that interview with Triplett: He told me that the local barber shop in my hometown of State College, Pennsylvania, didn’t take Black customers. He told me that there were certain places where you knew Black people weren’t welcome, and he told me that, until the dorms were integrated after World War II, most Black students lived at a boarding house off-campus.

In his article about that Penn State-Florida Gator Bowl, Derrick White refers to a speech by Martin Luther King, in which he clarifies that the terms “desegregation” and “integration” are two different things:

“Desegregation,” King said, merely removed the “legal and social prohibitions.”

“Integration,” King said, meant “the welcomed participation of Negroes into approved activities.”

Seventy-five years after Wally Triplett arrived on campus, Penn State’s student body—and the makeup of the surrounding small towns in central Pennsylvania who form the heart of Penn State’s football fan base—remains overwhelmingly white.

IV.

Fifty-five years ago, in 1970, Joe Paterno chose to start a Black quarterback named Mike Cooper. Paterno claimed he felt a connection to the Civil Rights movement because of the discrimination he experienced as an Italian kid in New York City; he had long been more progressive than many of his colleagues on social issues amid the protests of the 1960s. Yet when Penn State lost badly to Colorado in the second week of the 1970 season, and then lost games to Wisconsin and Syracuse, Paterno felt a kind of pressure he hadn’t experienced in his first few years as a head coach.

Fans began to call his home, demanding to speak to the “n——r lover” and threatening Cooper’s life. Letters poured in from fans claiming that players would never accept the leadership of a Black quarterback. One fan confronted a Penn State coach in the parking lot by declaring that Penn State needed to “get rid of that n——r at quarterback.”

Eventually, Paterno gave in, ostensibly due to the losing, though how much the outside pressure played on him is something he was still wrestling with, years later. He started a white quarterback, John Hufnagel, who won 16 straight games.

Cooper graduated after that season, became an activist, and gave up his ambitions of becoming a college football coach. Paterno, in his autobiography, wondered if Cooper believed that his coach had given in to the racists (Cooper declined to speak to Fox Sports columnist Jason Whitlock in 2012). It was a legitimate question to ask fifty-five years ago, in a small Pennsylvania town that had long ago embraced the idea of desegregation but was still wrestling with the question of integration. It remains a legitimate question to ask today.

This newsletter is a perpetual work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Respond to this newsletter, Contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please join the list and/or share it with others.