Randall Cunningham and the Journey of the Black Quarterback (October 10, 1988)

The NFL's Overdue Moment of Reckoning

Welcome to Throwbacks, a weekly-ish newsletter by Michael Weinreb about sports history, culture and politics.

I. “The Most Unbelievable Play I’ve Ever Seen a Quarterback Make”

Maybe it’s just me, but sometimes I wonder if this might be the most underrated play in pro football history:

It’s not just the sheer balletic poetry of that moment, the way Randall Cunningham takes that straight shot to the knees from a Hall of Fame-worthy linebacker named Carl Banks, props himself up neatly with his right hand as if the whole thing were part of a choreographed dance routine, then nonchalantly dodges the forceful charge of another Hall of Fame linebacker, Harry Carson, and then flicks a pass over several more defenders to a receiver streaking toward the sideline. It’s not just because this was Cunningham’s coming-out party on Monday Night Football in October 1988 for a national audience who had only been exposed to him in bits and pieces on SportsCenter, and it’s not just because I grew up a football fan in central Pennsylvania who had gravitated toward the Philadelphia Eagles for lack of a better option.

This, said Jimmie Giles, the receiver who caught the pass, was “the most unbelievable play I’ve ever seen a quarterback make.”

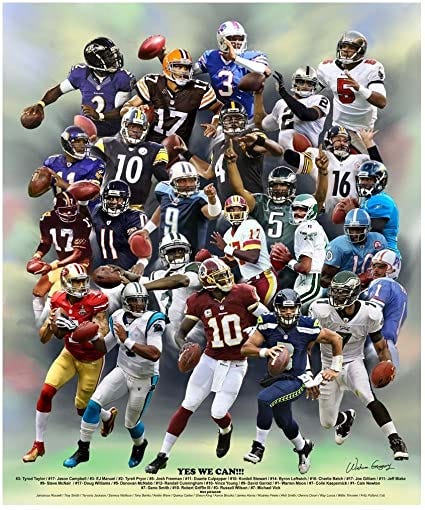

I will admit that this declaration hasn’t held up over the course of three decades. In the past few seasons, the best quarterbacks in the NFL, from Lamar Jackson to Patrick Mahomes to DeShaun Watson, have made plays like this almost every single week. We are in a golden age of quarterbacking in the NFL, an era when the notion of the staid and slow-of-foot passer is slowly dying, and part of the reason we are in that golden age is because of Randall Cunningham.

At the time, I had never seen a quarterback quite like Randall Cunningham before, and I imagine a lot of other people hadn’t, either. Cunningham did not fit the “pocket-passer” mold that had defined the NFL’s generations of almost exclusively white quarterbacks in the decades preceding this moment; but he was not a pure runner, either, which is how many of the black quarterbacks before Cunningham had been characterized (often unfairly). For decades, black quarterbacks from Marlin Briscoe to Joe Gilliam had been given partial chances, or given no chances at all; even in 1988, Doug Williams—who would become the first black quarterback to win a Super Bowl that season—was a pocket-passer who fit the parameters that defined what a quarterback should be.

This is not diminish the impact of Williams’ Super Bowl victory that year, because the sheer symbolism of it was a massive step forward. But Randall Cunningham was something completely different. Randall Cunningham was a brilliant athlete who also happened to be a brilliant quarterback, and in that moment, with the unfathomability of that single play, he began to shatter the stereotype of what a professional quarterback should look like.

“He had everyone in the neighborhood dropping back saying, ‘Randall Cunningham! Randall Cunningham!” a young black quarterback named Michael Vick told author William Rhoden for his oral history of black quarterbacks, Third and a Mile, and thirteen years later, in 2001, Vick—by modeling his game in part on Randall Cunningham’s—would become the first African-American quarterback to go first overall in the NFL Draft. It would take thirteen more years for Seattle’s Russell Wilson to become the second black quarterback to win a Super Bowl in 2014.

II. We The NFL

If it wasn’t already clear that America had reached a tipping point last week when it came to race relations, it became evident last Thursday, when a group of high-profile NFL players, including Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes, issued a video on social media demanding that the league recognize the Black Lives Matter movement, and that it acknowledge its own intransigence about these issues over the course of the past several years. Professional football is not just the most popular sport in America; it is arguably the most popular thing in America along with Netflix and bacon and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson.

Maybe you vehemently dislike the NFL as a corporate entity; maybe you despise NFL the bland villainy of commissioner Roger Goodell, and the oligarchy of hyper-rich owners to which he owes his own unfathomably massive salary. Maybe you have conflicted feelings about football’s inherent violence, and the concussion crisis that still threatens the future of the sport; but despite all that, more people pay at least some attention to football than pay attention to pretty much anything else in American culture. And it’s not just its sheer popularity that matters: It’s that the NFL is the most impactful organization in America whose talent is predominantly black. And for perhaps the first time in NFL history, the three most exciting young quarterbacks in the league, Mahomes and Jackson and Watson, are all black.

This is why it felt so important that the league itself, with Goodell as its white figurehead, finally conceded that it could not get through this moment without giving way to its black players. It almost didn’t matter that Goodell neglected to mention the name of perhaps the most impactful black quarterback in history, Colin Kaepernick—it’s now clear that Kaepernick’s stance has won over the majority of the public, and it is also clear that many NFL owners used Kaepernick’s on-field unconventionality as an excuse for refusing to sign him due to his off-field unconventionality.

The reaction to Drew Brees’ comments about respecting the flag were vehement for a number of reasons; but perhaps one of those reasons is because Brees is an undeniably great quarterback, but he is not representative of the modern NFL quarterback. The picture has changed. The classical idea of the most important position in the most popular sport in America has been altered, and that may feel like a modest point in the grand scheme of this moment, but it it’s a part of what got us here.

III. “Desirous”

It feels like a million years ago, but in 2003, ESPN made the retroactively perplexing decision to hire Rush Limbaugh as a pro football commentator. It’s no surprise that this blatant attempt to boost ratings ended in disaster. In 2003, amid a discussion about Eagles quarterback Donovan McNabb—the spiritual heir to Randall Cunningham’s dynamism in Philadelphia, and one of a new generation of black quarterbacks, like Vick, who refused to conform to the classical ideal of quarterback—Limbaugh declared that “the media has been very desirous that a black quarterback can do well -- black coaches and black quarterbacks doing well. There is a little hope invested in McNabb and he got a lot of credit for the performance of this team that he didn't deserve.”

There are, of course, so many problems with this argument that it’s hard to even know where to begin. For instance: Does Limbaugh really believe the media was more “desirous” that McNabb succeed than they were that, say Tom Brady or Drew Brees succeed? Given the controversial nature of McNabb’s career in Philadelphia, this argument seems even dumber in retrospect.

But more than anything, Limbaugh’s comments ignored the fraught historical weight of what it meant to be a black quarterback, and the decades of discrimination against black athletes who were denied even the opportunity to play the position—and that even when they were allowed to play the position, they were wedged into pocket-passer roles and viewed as too unintelligent to handle the demands of the position and too polarizing to serve as the symbolic figurehead of a franchise. There was so much of a push against black quarterbacks for so long, it felt reductive for Limbaugh to suddenly presume that they had any sort of tailwind behind them due to a vast bleeding-heart liberal media conspiracy.

And it made you wonder if the problem Limbaugh truly had with quarterbacks like Donovan McNabb was that, at some level, he didn’t feel comfortable with them being in control of anything at all.

This is why it felt like last week marked a pivot point. If you’re a white person and you haven’t spent these past couple of weeks examining your preconceptions of race, then you probably never will. But this is the power of a sport like football: It is so vastly popular, among literally every swath of America, that it is a way to bring these discussions to a mass audience, whether they like it or not. And this generation of black quarterbacks has done that, both overtly and subtly.

“Things like that aren’t supposed to happen,” Randall Cunningham said after that remarkable play in that Monday Night Football game in 1988, but things like that happen all the time now, and while it wasn’t easy getting here, and there is no guarantee that it will continue—it is still an utter embarrassment, for instance, that the NFL has only three black head coaches—things like that are going to keep happening if the NFL allows its greatest talents to express who they truly are.

Additional reading:

Third and a Mile, by William C. Rhoden

America’s Game, by Michael MacCambridge

Bringing the Heat, by Mark Bowden

This newsletter is very much a work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please subscribe and/or share it with others.