This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics, and everything in-between.

If you like what you read, please click the button below, join the mailing list for FREE and share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing.

And if you’ve been reading for a while, please consider a paid subscription to keep this thing going—you’ll also get full access to the archive of over 175 articles, like this one:

Author’s Note: I wrote this feature back in 2018 for ESPN, which declined to run the piece after I’d spent over a month working on it. In the wake of the controversy over Algerian boxer Imane Khelif, I thought it was worth revisiting. I know it’s long, but I hope you’ll spend some time with it.

I tried to update what I could, and while I am not an expert on this topic, I hope it at least conveys that the discussion of gender issues and sports should take into account the inherent complexities.

I.

Fifty years ago, in the weeks before the 1968 Winter Olympics in Grenoble, France, an Austrian skier named Erika Schinegger disappeared from training, returned to her home country, and then retired from competition altogether. On the surface, this news made no logical sense. Schinegger was 19 years old, a soft-spoken girl with a powerful frame who’d grown up on a farm in the southern town of Agsdorf; Sports Illustrated wrote that Schinegger skied like “a bull” in winning gold in the women’s downhill at the 1966 World Championships in Portillo, Chile. Given that she had recently completed a practice run only four seconds behind Austrian men’s champion Karl Schranz, there is little doubt that Schinegger would have been a favorite to medal at the Olympics, as well.

But then Erika vanished, subsumed into a burgeoning scandal that was largely beyond her comprehension, and driven into a personal nightmare that officials from Schinegger’s home country and the bureaucracy of the International Olympic Committee are still coming to terms with. And when Schinegger finally emerged again, after four surgeries and six months endured all on her own, with little support from friends or family, it was as a man named Erik.

Schinegger’s is a story that has rarely been told in English except in ski-specific publications, including a 2001 piece in Ski magazine with the tabloid headline, “Woman’s Champ Was a Man!” It’s a tale that largely escaped notice outside of Europe, in part because the majority of the historical controversy over sex-testing at the Olympics has centered around track-and-field athletes at the higher-profile summer games. But at a moment when we are only beginning, as a society, to come to terms with the fluidity of gender dynamics, the tale of how Erika Schinegger became Erik Schinegger, 50 years on, feels as relevant as it ever has.

II.

In at least one way, Schinegger was a pioneer: He was, for all intents and purposes, the first athlete ever banned from the Olympics for failing a chromosomal gender test.

It was an issue that no one in power seemed to wanted to fully confront in the moment, or even in the decades since: The conservativism of that era led everyone from the head of the Austrian Ski Federation (or OSV) to Schinegger’s own parents to believe that the story should be buried as fast as possible. Even after he re-emerged as Erik and began competing as a skier once more—winning three races on the Europa Tour in 1968 and 1969--the OSV refused to allow him to compete for his country. And the OSV will not, as of 2018, acknowledge his gold medal in 1966 (a medal that Schinegger himself eventually gave away to the second-place finisher, France’s Marielle Goitschel).

In 2008, the OSV, in its 100th anniversary program, omitted 1966 when listing its World Championship medals; in 2016, when an Austrian TV station wanted permission to make a documentary about the 1966 World Championships, the OSV reportedly refused to allow it (an OSV spokesperson did not respond to an e-mail request for comment on Schinegger).

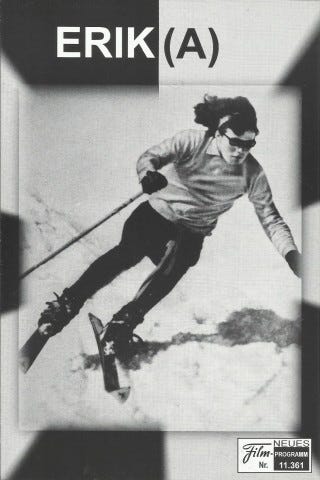

And so Schinegger, perhaps in part because he never felt fully accepted, has long taken it upon himself to keep his story alive: In the 1980s, he published a frank autobiography, and in 2005, he was interviewed by Austrian filmmaker Kurt Mayer for an honest and revealing documentary, Erik(A). In 2014, Schinegger appeared on Austria’s version of Dancing With the Stars.

“My life was a struggle to confirm me,” Schinegger tells me over e-mail, through a German translator. “That I’m not not a clown, but a precious man.”

“I was 16 when she became world champion,” says Reinhold Bilgeri, an Austrian singer/songwriter-turned-film director. “I saw all her races, and I read all the press stuff. It was a huge scandal, and the press made it even more of a scandal. They made him into a liar and a swindler. It was a very hard time for him.”

III.

In 2018, Bilgeri, in tandem with producer Wolfgang Santner, completed a German-language feature film about Schinegger’s journey from Erik to Erika. It is obviously not the first time Schinegger (who is married to his second wife, has a daughter, works as a children’s ski instructor near his hometown, and speaks very little English) has shared his story in his home country, but Bilgeri was hoping that perhaps he ccould finally propel Schinegger into a worldwide spotlight, and expose the biases that have long turned athletes with stories like Schinegger’s into pariahs.

And in so doing, he hoped, he could also help Erik Schinegger finally come to terms with himself.

“He looks like a happy man, but I feel like between the lines, he’s still got this problem,” Bilgeri says. “It’s only my opinion, but I think he’s still traumatized. It’s still a burden. He was so rejected by everybody. He could never really deal with it.”

IV.

In order to understand why Erika Schinegger was subjected to sex-testing in the first place, it might be best to begin in the late summer of 1938, when a ticket inspector on express train hurtling from Vienna to Cologne noticed something unusual. A man, he believed, appeared to be dressed as a woman. During a stopover in the German town of Mandeburg, the inspector informed a detective, who demanded to see the papers of the woman, a German high-jumper named Dora Ratjen. She was traveling from the European Athletics Championships in Vienna, where she had won a gold medal, and she showed the detective her ID card from the event; the detective, noticing how hairy Ratjen’s hands were, ordered her to come to the police station.

The detective pressed Ratjen. He threatened to subject her to a physical examination. If she resisted, he said, Ratjen would be found guilty of obstruction. And so Ratjen, who had finished fourth in the high jump at the 1936 Olympics, confessed that she was indeed a man. She was arrested for fraud—on her admission papers, the victim was listed as “The Reich”—and her gold medal was confiscated. According to the inspector, Ratjen confessed to being relieved that “the cat has been let out of the bag.”

Dora Ratjen soon became Heinrich Ratjen, and after being condemned as an imposter and as a tool of Adolph Hitler--as a man who had dressed in drag to satisfy the ambitions of the Reich, as a participant in a deliberate fraud meant to keep a German-Jewish high-jumper from competing in Berlin rather than, as turned out to be the case, the largely unwitting product of his own upbringing--he folded into German society after World War II and disappeared almost entirely from public view.

Only in 2009 did the German newspaper Der Spiegel uncover new information which showed that, in fact, Ratjen had been raised a girl by his parents after the midwife had initially identified her as a girl—when a doctor had examined her genitalia in childhood, he’d said, “Let it be. You can’t do anything about it anyway.” Ratjen was not, it would seem, a tool of Hitler: He was simply embarrassed and confused about his own identity.

It was into this post-war landscape, some nine hours from where Dora Ratjen’s train ride ended, that a baby girl named Erika Schinegger emerged into the world in the summer of 1948. She was born on a remote farm, to a mother later said she took a short break from working in the fields to have her baby. There was, said Schinegger’s mother in that 2005 Kurt Mayer documentary, a patch of “soft skin” in Erika’s genital region that worried her, but multiple doctors assured her it was just a growth, and that it would resolve itself naturally. And just as Ratjen’s parents had done, Schinegger’s parents took the word of their midwife: Their child was a girl, and would be raised a girl, even as they wondered if perhaps something was happening that was beyond the realm of their understanding.

V.

The notion of verifying that female athletes were actually female took hold soon after women began competing in the Olympics in the 1920s. By the mid-1960s, the rumors that attended track stars like Ratjen, American Helen Stephens, and Ukrainian sisters Irina and Tamara Press, had been heightened by Cold War paranoia. Athletes who, for whatever reason, didn’t appear feminine were subject to scrutiny by journalists and high-profile IOC members like Prince Franz Josef of Lichtenstein, who declared that he wished to be spared “the unaesthetic spectacle of women trying to look and act like men.”

This heightened the suspicion that Eastern Bloc countries might literally be dressing up men as women in order to gain a competitive edge in women’s sports. There is not one documented case of this actually happening, says Lynchburg College professor Lindsay Parks Pieper, author of a book about the history of sex testing in sports; in fact, many of the cases were similar to that of Dora Ratjen, in which a child grew up with intersex attributes that were never properly diagnosed.

And yet there was a clamor to do something. At first, the IAAF, the governing body of track and field, mandated visual inspections--in the wake of those inspections at the 1966 European championshiops, Time magazine ran a dubiously sourced story that claimed men cross-dressing as women was a legitimate issue, and that claimed Ratjen had been forced by the Nazis to dress as a woman “for the sake of the honor and glory of Germany.” (A narrative that was largely debunked years later by the Der Spiegel report.) The IOC, following the lead of the IAAF, instituted chromosomal testing for female athletes beginning with the Winter Olympics of 1968, at just the moment when Erika Schinegger appeared to reaching her competitive peak.

Schinegger was 12 when she ran her first ski race. She walked 14 kilometers to get there, and after starting in the last position out of 314 competitors, she won. Ski racing, as she endured the confusion of her teenage years, became “the only possibility for her,” Bilgeri says. “Erik was in-between chairs. He couldn’t find his identity.”

In 1966, Erika flew with her teammates to Portillo, Chile, for the first and only World Skiing Championship held in the southern Hemisphere. For Erika, who had hardly experienced the world outside of her family’s farm, the whole thing was exhilarating: On a steep and unforgiving course, she emerged to win the women’s downhill by eight-tenths of a second over Goitschel.

“Nobody really expected her to come out that well,” says Henry Purcell, the longtime owner of the Portillo resort where the championships were held. “She was a very powerful skier. She ran a very tight, well-controlled race.”

Her competitors remember her as genial and friendly. Yet she was also overcome with an inherent shyness about her physicality. Even as she became a hero in her home country—her hometown gifted her with a piece of land, her sponsor bought her gold-and-diamond brooch, and a young farmer sent her a marriage proposal in the mail—she began to question both her body and her feelings. Her face looked different, her chin more angular; other women were developing breasts and getting their periods, but she wasn’t. She found herself increasingly attracted to women. She endured taunts and quizzical looks, but she “never thought of being a man,” Bilgeri says.

“Though I don’t think any of us expected that she was actually a man,” says Canadian skier Nancy Greene, who competed against and befriended Schinegger, “in hindsight none of us were that surprised when it turned out that she was.”

“She was an anomaly,” says American skier Suzy Chaffee. “We suspected there was something weird going on.”

VI.

Before they arrived at the Olympics for testing, Schinegger and her teammates took a chromosomal gender-verification test in Innsbruck. A short time later, Schinegger was called back to Innsbruck, where she was confronted by a group of physicians and ski officials—all men—who presented her with a prepared statement to sign that she was resigning from the sport for “personal reasons.” They told her she could no longer compete in the Olympics or with the OSV. Two weeks later, she returned to the clinic for more testing, and was presented by doctors with a choice: Undergo plastic surgery and hormone therapy and remain a woman, or undergo multiple painful surgeries to become a man.

“For me, a world collapsed,” Schinegger says. “I cried. I screamed. ‘It can not be.’”

Meanwhile, rumors spread that Schinegger was going to have an operation of some sort, even if no one fully understood what that operation might be. “So we simply stopped talking about it,” Karl Schranz, the Austrian men’s world champion, told Mayer, the documentarian.

Schinegger, ignoring the exhortations of her parents, the OSV, and her ski sponsor, chose to transition and become a man. For months, he suffered through those four surgeries and his repeated recoveries, riddled with insecurities, 19 years old and completely alone. When he was finished, he went back home, re-introduced himself as Erik, and refused to hide away, even as many of his former friends and neighbors chose to avoid him. His hometown revoked the plot of land it had gifted him, and after the OSV refused to allow him to compete as a man, he retired from competitive skiing at the age of 21. And his case, because it had occurred outside of the Olympics itself, and because it “reified a binary classification of sex,” as Pieper wrote, allowed advocates of sex testing to continue to believe, for several more decades, that they were justified in attempting to pinpoint women who didn’t fit the classical definition of what a female athlete should look like.

VII.

So it went for at least a couple more decades, as Schinegger veered into his newfound masculinity in what he would later acknowledge was an almost clichéd fashion (“I always had to work on my masculinity,” he says). He bought a Porsche (he later admitted it was a “crutch”); he slept with multiple women before marrying his first wife, Renate, and his daughter Claire confesses that she long felt she served as little more than “living proof of his masculinity.”

Meanwhile, sex testing for athletes continued: The Polish sprinter Ewa Klobukowska was barred from the Olympics after failing a chromosomal test in 1967, and then gave birth to her son the next year. Edie Thys Morgan, who skied for the United States in the 1980s and later wrote one of the few definitive English-language profiles of Schinegger for Skiing History magazine recalls taking a gender test before the World Championships in 1987. When she asked why it was necessary, she was told, “Apparently there was an Erika who turned out to be an Erik.”

In 1992, after a high-profile challenge from Spanish sprinter Maria Jose Martinez Patillo and amid the objections of many medical professionals, the IAAF discontinued gender testing, and the IOC did the same in 1996. And yet the problems remain, and still are often spurred by public perception rather than by science. In 2014, the Indian sprinter Dutee Chand, who grew up in a mud hut in rural Eastern India to illiterate parents, was subjected to a gender test after competitors expressed concerns about her physique seeming “suspiciously masculine,” according to The New York Times. Chand—in the wake of Caster Semenya’s own high-profile case--mounted a legal challenge to the IAAF, which had abandoned all references to sex-testing but was still measuring for high testosterone levels (hyperandrogynism) based on “reasonable grounds for believing” that someone might have the condition. A court suspended those rules temporarily, but the IAAF passed new guidelines in 2023 that required athletes to lower their testosterone before competing.

Those who advocated for Chand continued to insist that the very notion of testing is based on a faulty premise.

“Where else do we allow this to happen?” Stanford professor Katrina Karkazis told me back in 2018. “You do not go get your driver’s license and they say, ‘I’m sorry, let’s test your testosterone’ and see if you can actually put an ‘F’ on your license….Where there’s the potential to be productive (with this conversation) is to introduce the idea that there is no bright line between male and female. There is no one marker you can use to classify people male or female. Nothing.”

VIII.

Looking back at the history, Karkazis’s premise starts to come into focus. Much of the justification for sex-testing has been based on public perception, on competitive innuendo, on a hegemonic notion of what a female athlete should be—and on stories seemingly based on false premises, like that of Dora Ratjen. “Much more must be done to adequately inform all stakeholders—participating athletes, sports officials, team physicians, the media, fans, and the public at large—regarding the complexity and fluidity of factors that contribute to competitive success as well as to sex or gender identity,” wrote three doctors in a Journal of the American Medical Association editorial in 2016.

No one felt the weight of that stigma in his formative years more than Erik Schinegger, who says that sex-testing is “against human dignity.” Bilgeri, the director also wonders what might have been if, he says, his home country had been more accepting at the time—if they’d understood that neither Erika Schinegger nor Erik Schinegger had intended to deceive anyone. That all he’d been trying to do was understand himself.

“Imagine,” Bilgeri says, “if he’d become a world champion as both a man and woman? That would have been huge. But instead, his career was destroyed forever.”

This newsletter is a perpetual work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Reply directly to this newsletter, contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please join the list and share it with others or consider a paid subscription.

Fantastic piece, important conversation—thank you for sharing it.

I never understood cheating in sports. What personal satisfaction do you feel when you cheated to win.