"A lifeless-looking creature with fun erupting all around him" (1988)

Bud Light, sports, manhood and Spuds MacKenzie

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics. Welcome to all new readers/subscribers, and if you like what you’re reading, please join the mailing list and share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing. (It’s still FREE to join the list: Just click “None” on the “subscribe now” page.) The best way you can help out is by spreading the word and sharing with others. That said, I have set up payment tiers, if you wish to chip in and allow me the time to do a little more research on on these posts—I’ve made them about as cheap as Substack will let me make them, which is $5 a month or $40 a year.

I.

What you see above is perhaps the nadir of late-1980s pop culture. How it happened was this: One fine day, some dude at an advertising agency in Chicago, brainstorming ideas for a new Bud Light advertising campaign, drew a sketch of a dog he called “Party Animal.” Based on this, Anheuser-Busch, the beer-brewing behemoth, set out to find a dog that resembled the drawing, which led them to a bull terrier named Honey Tree Evil Eye, who became rebranded as Spuds MacKenzie. I mean, you can almost hear the pitch in the room:

“Imagine Weekend at Bernie’s, but with a dog.”

“So the dog’s dead?”

“No, but he’s very relaxed.”

Spuds MacKenzie’s debut in 1987 would spike sales of Bud Light beer. He would ski and surf and go on spring break and dress up in tuxedos and appear on David Letterman; he was the clueless totem of an era when smart people tried to convince us that history was at its end. And he would also make a lot of people ponder—not for the first time, and not for the last—just how much a Bud Light commercial could expose the absurdity of the American experience.

II.

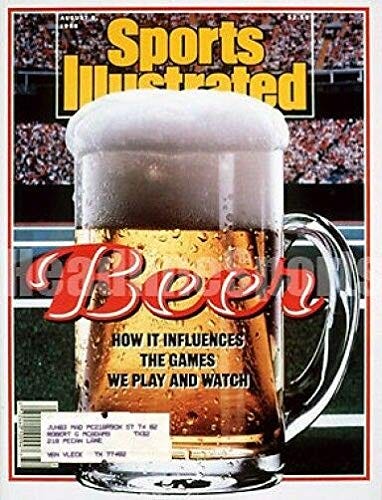

Sports and beer had long been demographically tethered, and in 1970, television finally caught on. That was the year the tobacco conglomerate Philip Morris bought the moribund Miller brewery, and according to a 1988 cover story in Sports Illustrated,1 “unleashed a high-powered marketing juggernaut that had been primed and perfected in the brutal cigarette-brand wars of the 1960s.” Eventually, Miller’s “Tastes Great, Less Filling” ads pitted intoxicated males against each other in the kind of nonsensical quasi-argument that mirrored an utterly incoherent 2 a.m. barroom debate about Led Zeppelin versus Black Sabbath.

These commercials linked beer and sports so closely that we all seemed to forget that alcohol and athleticism were actually paradoxical partners—and that their presence together on our television screens was, in many ways, a uniquely American thing. In 1985, when the football star Bubba Smith—star of many of those Miller Lite ads—returned to his alma mater at Michigan State, he heard a stadium full of intoxicated people chanting, “Tastes great! Less filling!” And right then, Smith decided to quit doing the ads.

“We could never think of it," the director of the Austrian ski federation told SI in 1988. “Sports and alcohol should never be placed together.”

But in America, anything was possible. In America, with a little luck and the right attitude, a humble hound could become a party dog. And so with Anheuser-Busch looking to keep pace with Miller, Spuds first appeared on screens during the 1987 Super Bowl. Spuds soon became more than just a moronic concept brought to life: Spuds became a phenomenon. And why? Who the hell knows why? One of the company’s own P.R. people characterized Spuds as a “lifeless-looking creature with fun erupting all around him.” A marketing executive shrugged and told SI, “We still can’t explain it.”

Spuds inspired an entire line of clothing and stuffed toys; his cultural omnipresence, particularly among children, managed to piss off both Mothers Against Drunk Driving and Strom Thurmond. Why? Who the hell cares why? When asked by one newspaper columnist whether the Spuds party-animal image might actually encourage destructive behavior among young men—or whether it might actually be targeting underage drinkers—that company P.R. person asked, earnestly, “What do you mean?”

III.

Around the time that Spuds MacKenzie reached his cultural zenith, a handful of academics—including the legendary cultural critic Neil Postman—released a study titled, “Myths, Men & Beer.” What it revealed was not exactly surprising: It showed that men in beer commercials spent their leisure time either engaging in outdoor sports or hanging out, primarily in bars. It claimed that men in beer commercials were limited and simplistic: “We found no sensitive men... nor any thoughtful men, scholarly men, political men, gay men or even complex men,” they wrote. And the women? They were merely the audience for the performative aspect of male friendships.

In summary, the authors wrote, the men and women of beer commercials were “almost laughably anachronistic.” Which brings us to the now, to an impossibly stupid controversy over a new era of Bud Light promotions, one that has led a far-right rap-rocking doofus to take a machine gun to a case of beer. And why is it happening? It’s happening because a certain sect of laughably anachronistic people somehow seem to believe that a beer brand attempting to alter its public image somehow infringes on their own gender identity—a beer brand that once made a lifeless dog famous simply by surrounding him in the trappings of masculinity. Which, come to think of it, is actually a pretty concise summary of Kid Rock’s career.

“There were reports (Spuds MacKenzie) had died in a plane crash, been electrocuted in a hot tub, or drowned while strapped to a surfboard during filming, all orchestrated by (Anheuser-Busch),” wrote Beatrice Kanner in her book The Super Bowl of Advertising. In truth, the real Spuds died from kidney failure in 1993. (I suppose that’s what happens when you repeatedly force a bull terrier to drink enough low-grade light beer that it willingly rides a skateboard.) And by then, we knew Spuds’ secret: The dog who had come to embody the bro-ish culture of the late 1980s in America—the dog who may have convinced Kid Rock to drink Bud Light in the first place, by virtue of its comparatively superior intelligence—was actually a girl.

This newsletter is a perpetual work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Reply to this newsletter, contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please join the list and/or share it with others or consider a paid subscription.

The fact that SI devoted an entire cover story to beer culture is just another example of how remarkable this magazine once was.