Why do we hate Tom Brady? Why do we love Tom Brady? (February 3, 2002)

Half a dozen views on No. 12

This is Throwbacks, a weekly-ish newsletter by Michael Weinreb about sports history, culture and politics. Welcome to all new readers/subscribers, and if you like what you’re reading, please subscribe and share. (It’s still free: Just click on the free option on the “subscribe now” page. If you do wish to contribute, see below.)

I.

On the third day of February in 2002, in a nation consumed by fear about both its immediate and long-term future, in a city that would soon be permanently altered by the encroaching threat of climate change, the New England Patriots took the field for Super Bowl XXXVI. They chose not to be introduced one-by-one, as is tradition for a Super Bowl; they chose to be introduced all at once, “as a team,” inside the New Orleans Superdome.

This, of course, was an idea torn straight out of the Sports-Movie Cliche Playbook. It was the kind of thing that teams do in order to reinforce their bond, and with the Patriots a twelve-point underdog to the St. Louis Rams, and resting their hopes on the arm of a first-year starting quarterback named Tom Brady, they needed all the solidarity they could muster. But it was also a clever gesture that comported with the mood of the nation: America was on edge, unsure if our values would endure in the midst of impending war and ongoing terrorist threats. The Patriots, in their red, white and blue uniforms, came to symbolize our unity in the face of disaster. They became “The United Team of America,” wrote author Rosabeth Moss Kanter, and for the vast majority of you who, two decades later, find the New England Patriots to be a cold and arrogant and emotionless franchise that dominated the NFL over the course of an era when America’s national cohesion systemically unraveled, I will now pause for a moment to permit you to choke back your nausea.

II.

Every generation has a football team that comes to represent the Zeitgeist, and that team, in the era between 2001 and 2019, was the New England Patriots. They are now largely reviled in the vast swath of the country that lies south and west of Hartford: For their insufferable perfectionism, for their endless array of stockpiled talent, for the bluntness and condescension of their coach, and for the glossy perfectionism of their quarterback—and, of course, for the complex scandals that branded them as ruthless mercenaries willing to do anything to win, and that their proponents dismiss as nothing more than political paybacks from their enemies. It’s hard to even recall that the Patriots were once an underdog, a metaphor for our enduring national connection in the aftermath of one of America’s darkest moments, and that their quarterback, before he became the most successful football player in the history of the game, was also a prototypical underdog story, at least before he became one of the most famous and most reviled athletes in America.

III.

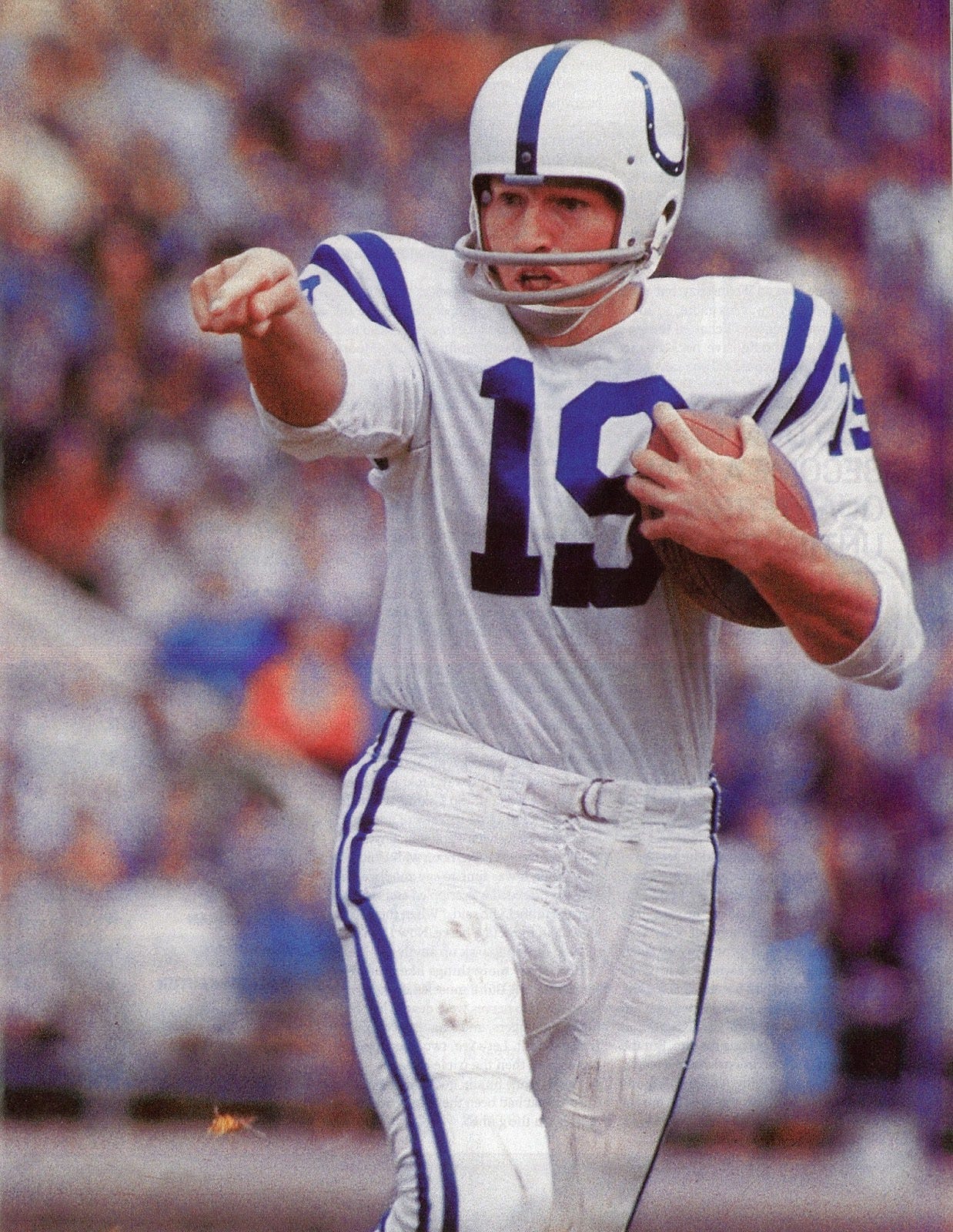

In the same way that dominant teams become representative of an era, every generation has a quarterback who comes to define it—at least since the 1950s, when, as the popularity of football eclipsed the popularity of baseball, quarterback became the defining position in American sports. In the 1950s, it was Johnny Unitas, with his clean lines and his Beaver Cleaver crew-cut; in the 1960s, it was Joe Namath, with his shaggy visage and brash counterculturalism. In the 1970s, it was (arguably) Terry Bradshaw, a slightly overrated punchline with a bad haircut; in the 1980s, it was Joe Montana, a cool and affable and ruthlessly efficient proxy for the Reagan era.

It gets a little fuzzier from there, as the sheer number of great quarterbacks proliferated into the 1990s and beyond—perhaps Brett Favre, a politically incorrect southerner with an allegedly wandering eye, was the defining quarterback of the Clinton era?—but then here came Brady storming into the 2000s, winning one Super Bowl and then another and then another until he had two rings for his thumb.

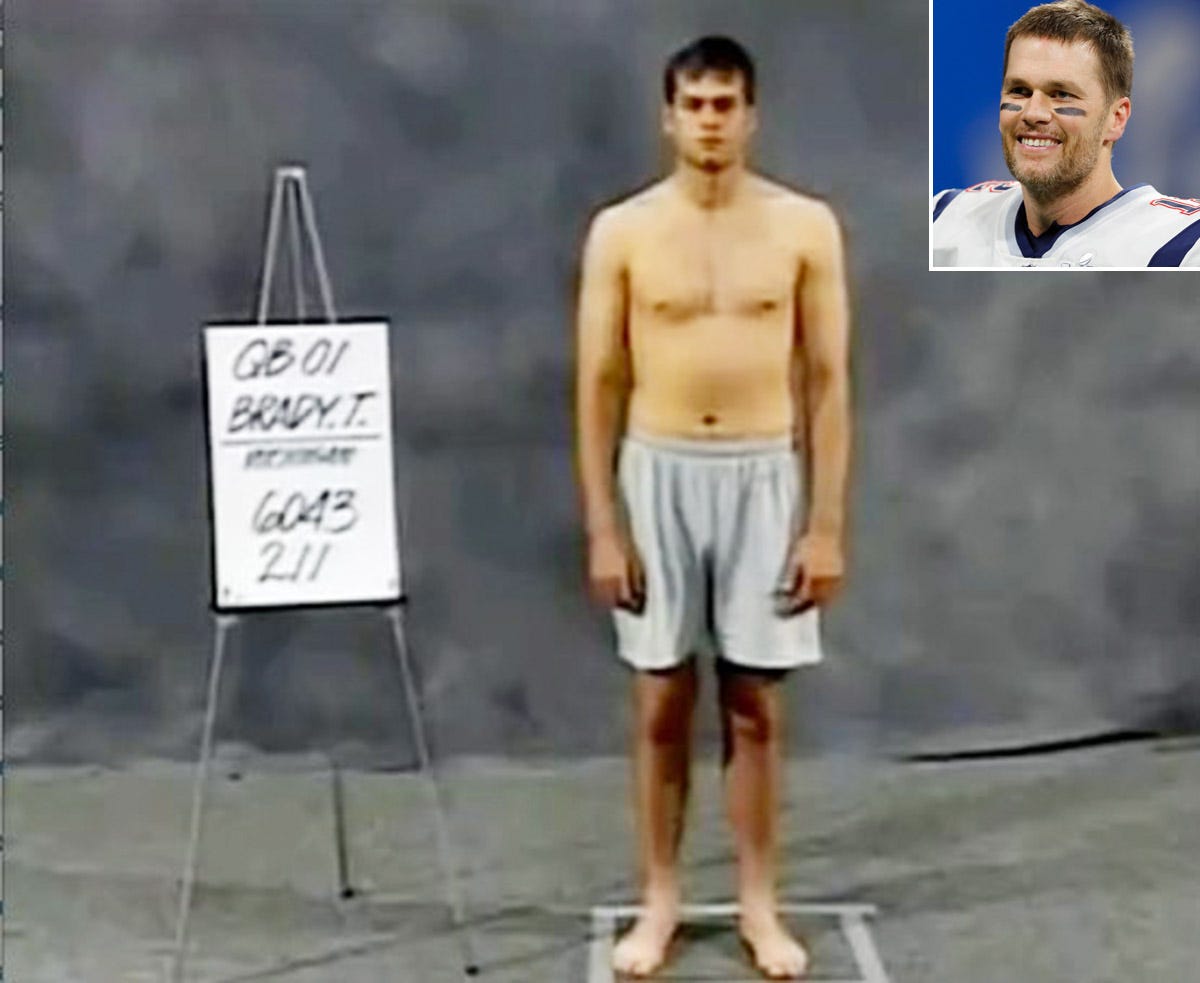

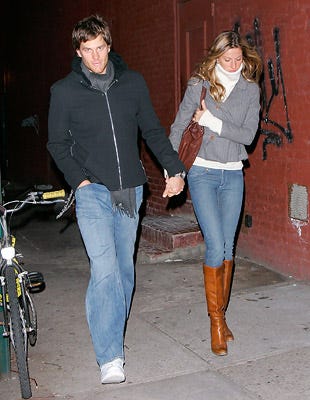

In those early years, Brady was viewed as kind of a miracle of advanced scouting, a relative unknown drafted with the 199th pick of the NFL draft who molded himself into the most successful quarterback of his era. But eventually, that “disrespect” cliche grew tired; once Brady married a supermodel and posed in Ugg boots and began adhering to a diet so strict that his entire persona morphed into a running joke about nightshades and strawberries and electrolytes, he became something else altogether. He was rich and he was famous and he was undeniably great, but he wasn’t even remotely relatable. He was purely a brand. It felt as if he had no vices beyond his own serial competitiveness; to a segment of the NFL’s testosterone-worshipping fan base, he was too damned metrosexual to be respected.

Still, Brady became the embodiment of winning in a country where winning means everything. He was like the actualized product of a million self-help videos. In an era where social media profiles were engineered to present a glossy version of their existence, with all the rough edges sanded away, Tom Brady seemed to actually be living that life.

And for this, we came to love him.

And for this, we came to hate him.

IV.

There is nothing overwhelming about watching Tom Brady play football. He does not dominate. He does not wow very often, except with the consistency of his competence. Maybe this is why it’s so easy to presume there must be something up with the dude—like maybe he really was deliberately deflating footballs to gain a competitive edge, and maybe he was aware of Spygate, and maybe that means he’s somehow been pulling the wool over our eyes the whole time, a Gatsby throwing fade routes.

One serially lazy sports columnist wrote this week (I am not even going to bother to link the piece, because there really is no substance to the argument) that Tom Brady is not the Greatest Quarterback of All-Time, but the Luckiest Quarterback of All-Time. Even now that he’s broken away from the Patriots and now that the Patriots struggled without him and Brady’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers are now one win away from the Super Bowl, some would claim this is merely further proof of his luck.

Brady no longer dominates a football game, but then, that wasn’t ever the way he did things. He just didn’t make mistakes. He cleanly navigated and managed football games until it was time to win them. And then, most of the time, he did that, too.

And for this, we came to love him.

And for this, we came to hate him.

V.

In 2008, with the Patriots on the verge of completing only the second undefeated season in NFL history, my friend Chuck Klosterman wrote a column for ESPN (anchored by the above photograph) that posited that Brady would be better off losing the Super Bowl to the New York Giants. This, Chuck wrote, would make Brady more interesting in the long run.

Of course, Brady did lose that game, amid a flurry of bad play and bad luck and footballs pinned against helmets by journeyman wide receivers. It became the lowest moment in a career marked almost entirely by highs; it was arguably the most unlikely loss in Super Bowl history, and arguably the most interesting moment of Brady’s career. But here is the irony: That game, and that loss, did not make Tom Brady any less representative of perfection. If anything, it made him seem more perfect (if such a phrase can exist, outside of the United States Constitution); it propelled him into the second stage of his career, when he would win more Super Bowls and become an avatar of the American Dream.

Last year, in the wake of the online frenzy of The Last Dance, ESPN announced that it would give Brady the same treatment it gave Michael Jordan: A nine-part series about his life and career. And the reaction online was one of complete indifference, if not outright revulsion. The only reason The Last Dance held any interest is because Jordan was willing to speak honestly and frankly about his competitive nature; Jordan’s entire career was fueled by grudges and anger, and all of that emerged in the documentary. But while we’ve all seen Tom Brady get angry on the sideline, I don’t think Brady has that same instinct for pure public vengeance. I can’t imagine Tom Brady would be willing to pierce his bubble just to allow the people outside of that bubble an honest glimpse at who he is. What would be the point of that? In our minds, he’s already perfect.

VI.

Last week, in the wake of a win against the New Orleans Saints that left Tom Brady one win away from playing in yet another Super Bowl, a video surfaced of Brady talking to New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees and his children. It is a nice video, of two seemingly decent men. It makes you think that Tom Brady is probably a good father to his own children.

The closest Brady’s public image came to unraveling happened in 2015, when reporters spotted a Donald Trump campaign hat in his locker. Way back in the days when Brady was evolving from a sixth-round draft pick into a major celebrity, he judged one of Trump’s beauty pageants; according to author Charles P. Pierce’s book Moving the Chains, Trump became “a new very close friend.” It is easy to imagine that Trump, given his myopic self-regard, viewed Tom Brady as a kindred spirit, a serial winner who presented a flawless image of opulence and success to the country. And for Brady, I imagine Trump was nothing more than a dude he could chase girls and play golf with back when he was young. It was almost as if Brady was entirely out of touch with what the consequences of that friendship could even be once Trump chose to run for president on a platform of bigotry and anger—which is exactly what we’d come to expect from the older Tom Brady, who was too busy modeling cardigans and studying film to pay much attention to the consequences of his actions outside of football.

In the end, maybe that’s how we’ll remember him: As someone who seemed to float above it all—a great quarterback who was little more than that, a dude with one hell of a great life who hermetically sealed himself from the outside world. That’s not his fault, really: He is just a quarterback to us, and he’s probably the greatest quarterback we’ve ever seen. He may, in fact, be a good father and a nice man. But in America, quarterbacks become symbols, and years from now, when we look back on this contentious period in American life, Tom Brady will stand above it all as a symbol of perfection, even as the country raged and fractured all around him over the course of nearly two decades. And for that, we will both love him and hate him.

This newsletter is very much a work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please subscribe and/or share it with others.

I am keeping this newsletter free for now. The best way you can help out is by spreading the word as much as possible so I can expand my audience, because I am a terrible self-promoter. That said, I have set up payment tiers, if you wish to give something—I’ve made them as cheap as Substack will let me make them, which is $5 a month or $30 a year. If you do wish to pay, I’m happy to send you a signed copy of any one of my books as a thank you. Just shoot me a screenshot and a book title (preferably a book I wrote, but if you prefer me to send you a copy of The Corrections, I’ll do that, too), and we’ll work something out.