Why do sideline interviews exist? (1974)

How Gregg Popovich exposed and mocked the thing that no one wants.

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics, and everything in-between.

If you like what you read, please click the button below, join the mailing list for FREE and please share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing.

And if you’ve been reading for a while, please consider a paid subscription to unlock certain posts and help keep this thing going—you’ll also get full access to the historical archive of over 250 articles. (Click here and you’ll get 20 percent off either a monthly or annual subscription for the first year.)

(If your subscription is up for renewal, just shoot me an email and I’ll figure out a way to get you that discount, as well. If you cannot afford a paid subscription and would like one, send me an email and I’ll comp you one, no questions asked.)

I.

It was an idea born 50 years ago in the midst of a tragedy, but as with many ideas that become co-opted by network executives, it soon devolved into a Chayevskyian parody of itself. The way Jim Lampley told it to Deadspin’s Tommy Craggs, the advent of wireless technology was first utilized to noble ends, enhancing ABC’s coverage of the Israeli hostage crisis during the 1972 Munich Olympics, but then the powers that be began to ask how else they could use this technology. That led to a good thing—the hiring of Lampley, who would become a fiercely intelligent broadcaster—even as it contributed to the inevitable dumbing down of nearly every sporting event over the course of the next several decades.

Lampley was a graduate student at the University of North Carolina when ABC plucked him from obscurity to work a new job: He would be employed as a sideline reporter during college football games, starting in 1974. Years later, he admitted to Craggs that he had inadvertently helped create a monster, and that the whole idea of on-air sideline reporting was a useless and insignificant appendage to a television broadcast.

“I’d get rid of it entirely,” Lampley said in 2009, and yet 15 years after he uttered those words, the concept hasn’t gone away. It’s just morphed into something worse. The sideline reporter is involved in more awkward moments than ever, even though literally no one seems to want this other than the executives who have declared it a necessity.

II.

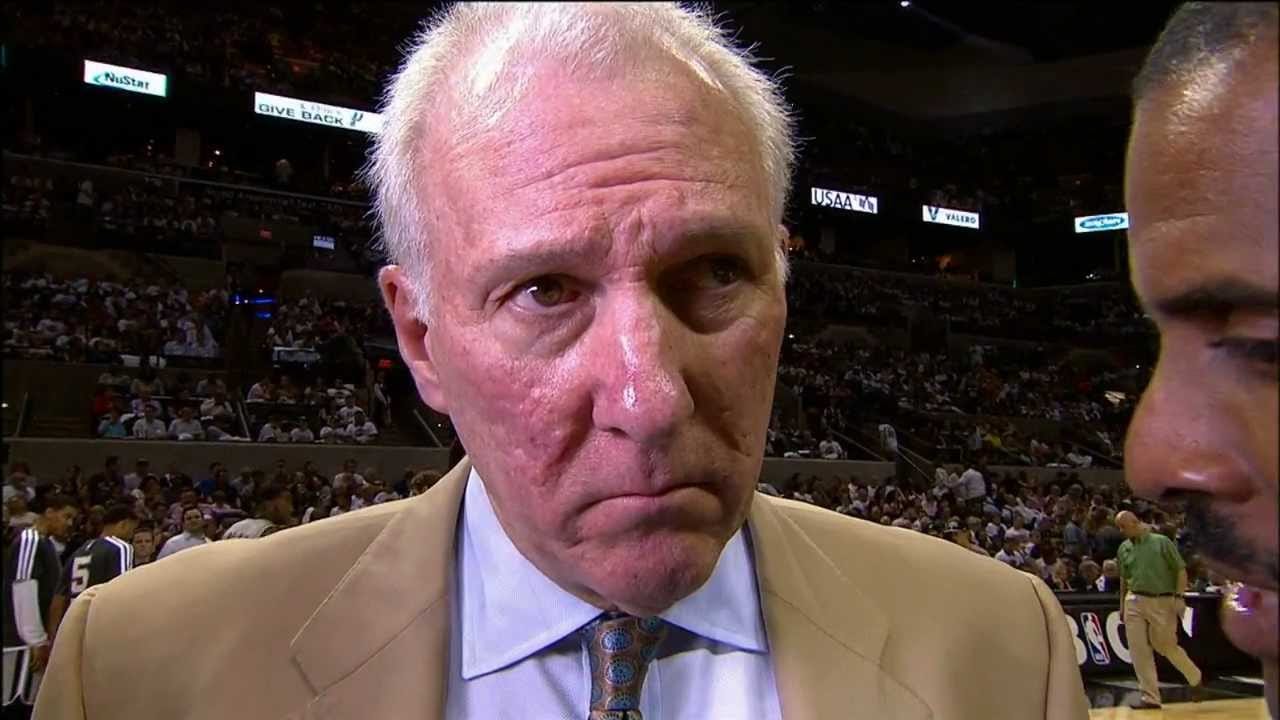

Of all the performatively absurd sideline interviews Gregg Popovich conducted in his coaching career, my favorite is this existential exchange with TNT’s David Aldrich:

Over the course of those 42 seconds, Popovich—who announced his retirement from coaching this week—managed to espouse a Nietzschian view of the universe while mocking the very idea of the mid-game interview he was forced to give by the NBA. Aldrich, like Lampley, is an excellent reporter who fully understood that he was the foil here in this kabuki exercise—that there are no good questions to ask in this situation because, as Popovich declares, “We’re in the middle of a contest, nobody’s happy.”

That says it all, right? Any thoughts that any coach espouses are not going to be fully formed in this situation; it’s just a needless obstacle for them to get through before they head back to their team, and for that reason, it is truly pointless.

For years, Popovich attempted to reinforce that point by turning every sideline interview into a Samuel Beckett play. At times, his distaste for the concept bordered on cruelty, as when he nearly made Doris Burke cry, and for that, I’m sure he harbors regrets. But as is often the case with Popovich, his manner may have been gruff, but his overarching point was correct. The sideline interview is a needless appendage that network executives have insisted on grafting onto our experience without taking into account whether we actually care. Thanks in large part to Popovich, the awkwardness of these exchanges has now become our expectation, and I suppose that’s why they persist—it’s a literal poking of the Bear. The network executives have decided that if they can do something, they will do something, even if it’s only to make us squirm.

Here’s this week’s previous newsletter, in case you missed it:

III.

“Fans want to be closer to the game, they want to get to know the players and the coaches,” one NFL executive said about the league’s increasing reliance on in-game interviews. “It’s very important that they kind of have that relationship.”

Those words were apparently spoken in court, during a trial over the NFL’s Sunday Ticket broadcast rights, and somehow lightning did not strike the speaker down. Because, I mean, come on—these interviews do not help us get to know anyone. In fact, they actively ward us away. As Sportico’s Anthony Crupi wrote last year, they are the spiritual successor of the Marshawn Lynch press conference in which he endlessly repeated, “I’m here so I won’t get fined.”

I can’t think of any reasonably sober sports fan who would disagree with this take, and yet the thing is, what are we supposed to do here? How do we make it stop? It’s not like I’m going to boycott watching a game because ESPN insists on conducting an awkward end-of-first-quarter interview; it’s not like we’re going to start organizing collective protests in the background of these camera shots. The mid-game sideline interview is forced down our throats because the people in charge can do it…because the momentum grew, and then everyone started to do it and now they can’t stop doing it. It has nothing to do with getting us closer to the game. You want us to get us closer to the game? Give us clips from a mic-ed up sideline or team huddle or locker room; give us a sense of what it looks like and feels like out there and have a sideline reporter accrue information that actively advances our understanding of the game. How does mindless drivel spewed on-camera by distracted coaches advance our understanding of anything, except their distaste for the very concept?

Gregg Popovich is a smart man with a lot to say, if you afford him the proper platform. So, too, are Jim Lampley and David Aldridge. To wedge them into a format that no one wants does a disservice to them all, and the greatest tribute the NBA’s new television partners could pay to Popovich would be to tone down the bullshit and up the level of intelligence. But we know how this works. Popovich can rage like Howard Beale in Network, but nothing will change. “Television is a God-damned amusement park!” Beale said. “Television is a circus, a carnival, a traveling troupe of acrobats, storytellers, dancers, singers, jugglers, side-show freaks, lion tamers, and football players,” and we are captive to it all, as useless and insignificant as it might be.

This newsletter is very much a work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please subscribe and/or share it with others.

You're on a heater you Nittany. But you're howling into the void here. Love your work.

Excellent observation. Thx for bringing Popovich into this reasonable ask to just, please, stop.