"There's no there there" (1973)

Las Vegas may have bought the A's, but there's one thing it can't buy

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics. Welcome to all new readers/subscribers, and if you like what you’re reading, please join the mailing list and share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing. (It’s still FREE to join the list: Just click “None” on the “subscribe now” page.) The best way you can help out is by spreading the word and sharing with others. That said, I have set up payment tiers, if you wish to chip in something or “leave a tip”—I’ve made them as cheap as Substack will let me make them, which is $5 a month or $30 a year.

I.

Fifty years ago, the Oakland Athletics were the best team in baseball, and the Oakland Raiders were one of the best teams in pro football. They were also franchises that reflected the ethos of their city: They were tough and unkempt and rebellious, and they played in a concrete bowl of a stadium surrounded by train tracks and warehouses. Both teams’ owners were obnoxious and showy pricks. They were, collectively, the Hell’s Angels of professional sports.

Over time, as Oakland’s soul evolved—as it became something far more compelling than the “no there there” place that Gertrude Stein once referred to it as (which even in itself was a quote largely devoid of context)—that image changed. The Raiders moved to Los Angeles, moved back, and became free-form mercenaries led by an erratic patriarch and his dimwitted son, before they left for good. The A’s won a World Series in 1989 that is most closely associated with the birth of the performance-enhancing drug era, and then, as Oakland gentrified during the tech era, the A’s became known as a team that managed to compete despite never having the money to truly complete, the underdog of all underdogs. So much so that their strategy eventually swallowed baseball—and society—whole.

And now that era is gone. And so, too, are the A’s, to a city where there truly is no there there at all.

II.

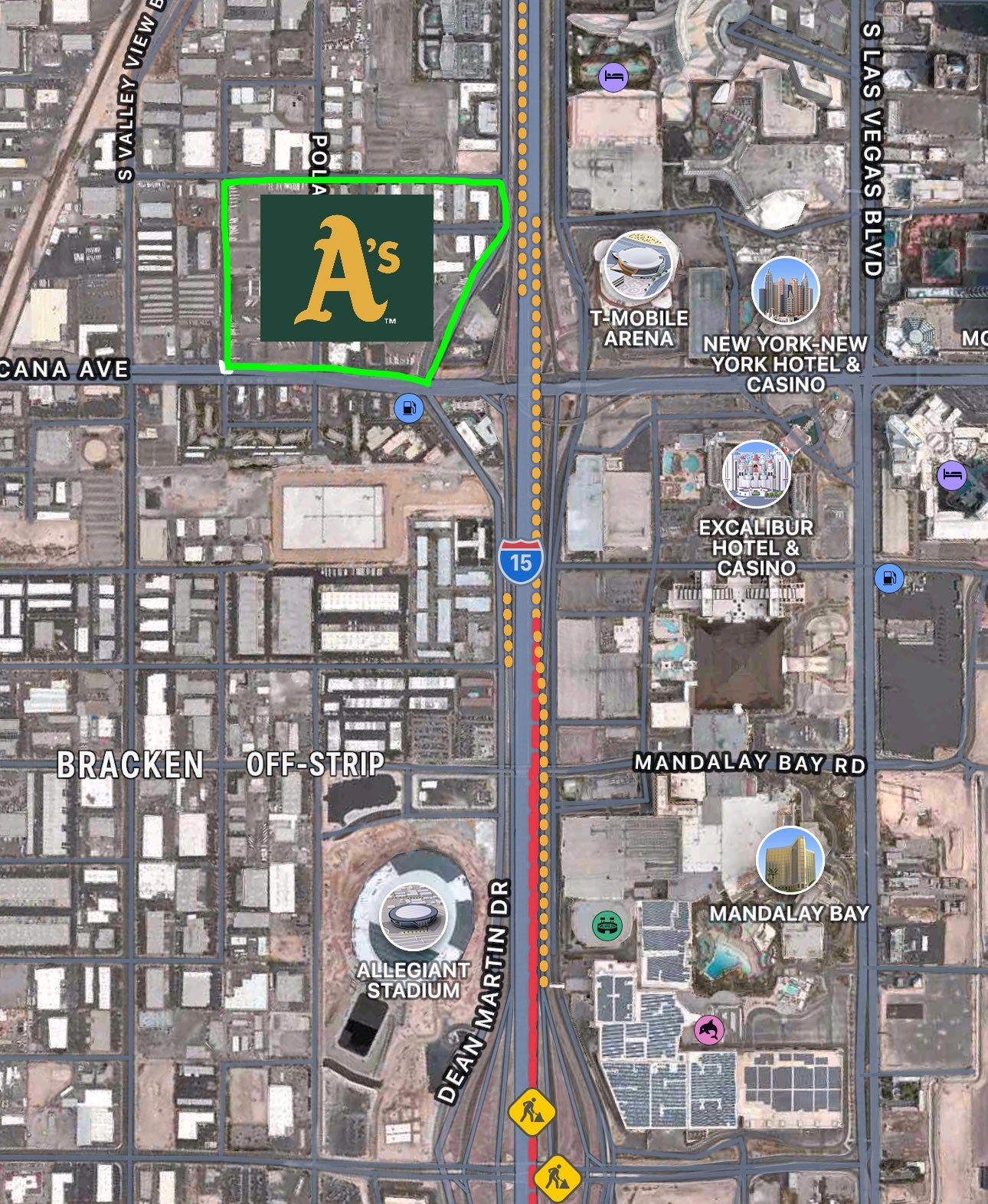

What you see above is a map of the A’s future, via Las Vegas Review-Journal reporter Mick Akers, after the team announced it had struck a land deal in Las Vegas. It is the planned layout of a insipid sports district in a spiritless city, one that attracts millions of visitors a year by sheer virtue of its lack of a soul. People come to Vegas to indulge their worst instincts and to do things that they cannot do anywhere else, and then they leave their detritus behind for the residents to clean up. It is amazing that a place so loud and so bright could be so lacking in any sort of actual personality, but so it goes.

Of course, there is a lot of money in sin, and that makes it attractive to sports owners who have worn out their welcome in their current cities, as was the case with both the owner of the Oakland Raiders and the owner of the Oakland Athletics, the latter of whom inherited his money from his parents, the founders of a company that trademarked blandness as a fashion statement. And I know there is a lot of complex three-dimensional politics involved in this decision-making, and as someone who recently moved to Oakland, I also know that Oakland’s rampant civic dysfunction is a real thing, so the city deserves some of the blame here.

But I also know that Oakland had spent years trying to negotiate a deal with the A’s that wouldn’t require a raft of public funding; I also know that several other people angled to buy the team and keep it in Oakland, including Warriors owner Joe Lacob. I know that there were ways to get this deal done, and the A’s apparently had no real interest in getting it done, which is the way these things go sometimes. They saw a sexier market in a city that’s (probably) willing to give them taxpayer money, and they jumped at it. As I wrote about the Raiders a few years back:

This is an age-old story by now: fans getting fucked over by circumstances out of their control, by the push and pull between city officials and millionaires. It’s happened in Cleveland and Baltimore and St. Louis (twice) and Houston; it could happen in San Diego; and it’s happened once already to Raiders fans, when Al Davis absconded to Los Angeles in defiance of NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle’s wishes back in 1982. That act of rebellion is the root of the bad feelings in Oakland that linger today, because the city issued nearly $200 million in bonds in order to build luxury boxes at the Coliseum to lure Al Davis and the Raiders back to Oakland in 1995, and Oakland taxpayers are still paying off that debt. In the ensuing years, the Coliseum has devolved into a crumbling dump, the worst stadium in professional football (and professional baseball, since the Athletics are stuck there too for the moment). The toilets are notoriously prone to overflow and leakage, and problems with power and lighting are an ongoing issue; the concession options are minimal, and the stairways are pocked and rusted.

III.

All of that remains true; the Coliseum is literally a habitat for possums nowadays. And it is easy to feel cynical about it all—to parrot the economists’ notion that sports stadiums have become a game of welfare for billionaires. (That attitude also fits into a certain radical political bent in Oakland that dates back to the era when the A’s dominated professional baseball.) But I think that piling that sort of cynicism on top of cynicism ignores one of the core reasons that sports exist, which is that they can restore and reflect and embody the character of a city or a town or a community.

Maybe you might say that sports aren’t totally necessary for the lifeblood of a city, but in that case, is anything really necessary? Are we just living our lives to survive day-to-day? There is an emotional reward that a hometown sports franchise offers; there is a sense of civic pride that transcends the financial picture. And that’s what Oakland loses now, having lost every single one of its pro sports teams.

Maybe becoming a big-time sports town will succeed into turning Las Vegas into something more than a hellscape of strip malls and strip clubs and smoke-filled slot parlors and Adele residencies and bad T-shirts and Guess Who reunion tours and second-tier restaurants brought to you by first-tier chefs, but I kind of doubt it. Because you cannot engineer a city in reverse like that. Oakland had a soul long before it had sports teams; the sports teams just helped reveal that soul to the world. Meanwhile, one of the first questions that someone asked on Twitter when Akers revealed that map of the A’s new stadium was a panicked query as to whether they were going to build it right over the In-N-Out Burger, which is further proof that a city cannot purchase a soul, no matter how hard it tries.

This newsletter is a perpetual work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Respond to this newsletter, Contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please join the list and/or share it with others.

Good article, though you missed a few things.

The A's were never exactly beloved in Oakland, for example. Charley Finley's attempts to move them in the late 1970s failed, resulting in the 1979 A's, one of the worst teams in baseball history. Having said that, it's not like the A's of the early 1970s had excellent attendance figures or a great local following, either.

But, as you mentioned, the real tragedy here is the fact that these municipalities decide to publicly fund stadiums to attract teams. It's always a bad idea.

I grew up in Salt Lake City, where public money paid for a new AAA ballpark back in 1994 or so, despite quite a bit of public backlash. They're currently working on building a replacement for that "old" ballpark, one that I believe is also funded by public money. It amazes me that owners continue to successfully convince local politicians to spend silly amounts of taxpayer money funding public stadiums — and I say that as a lifelong fan of the sport.

I will say the Coliseum is a great place to watch your favorite teams who are not the A’s