This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics, and everything in-between. Welcome to all new readers/subscribers, and if you like what you’re reading, please join the mailing list and share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing. (It’s still FREE to join the list: Just click “None” on the “subscribe now” page.) The best way you can help out is by spreading the word and sharing with others. I have set up payment tiers, if you wish to chip in and allow me the time to do a little more research on on these posts. You’ll get full access to the archive of more than 100 previous posts, as well.

I.

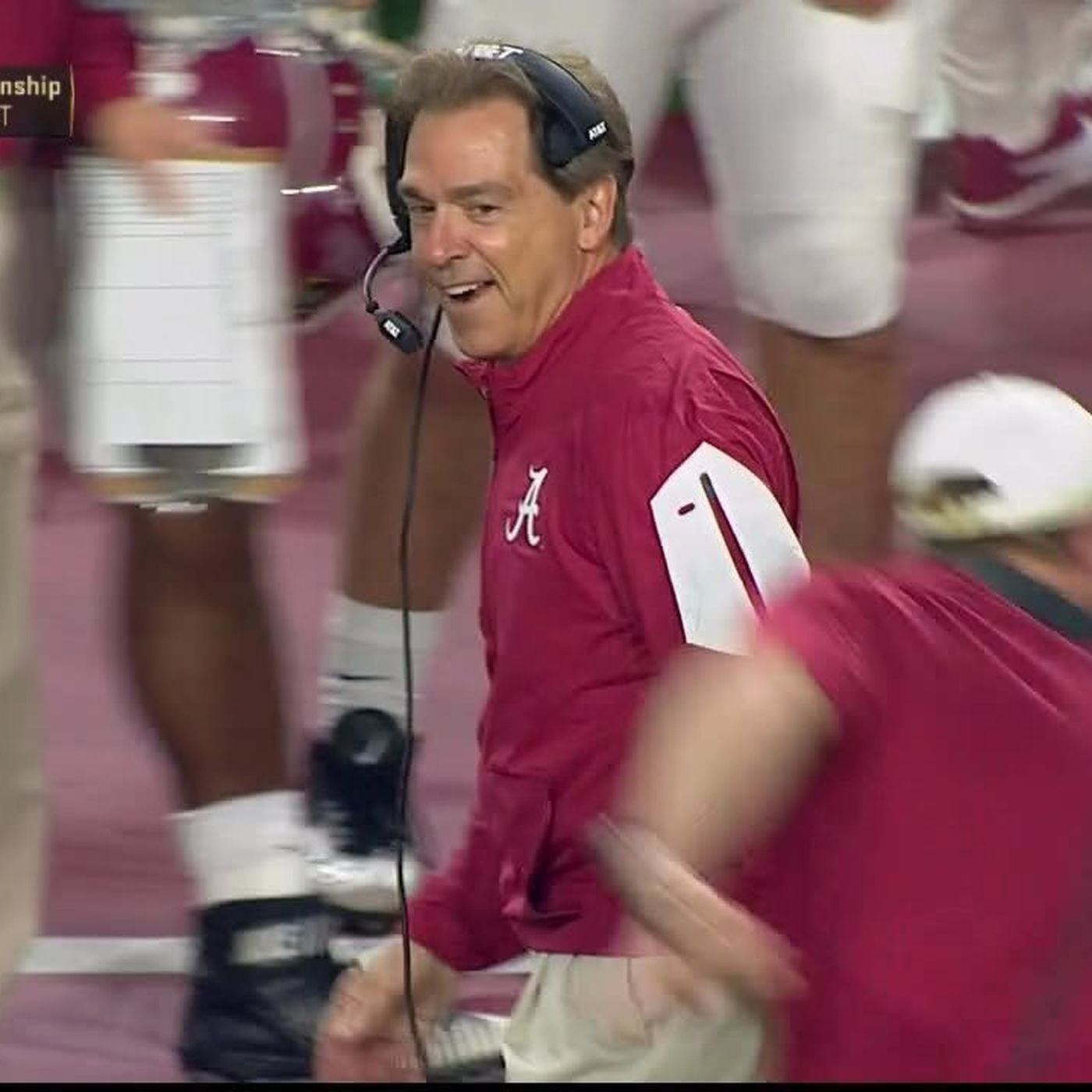

Here is a video of the greatest college football coach of all time performing a choreographed line dance:

This was in 2018, when Nick Saban was at the peak of his powers; when he had won two national championships in three years, when he had won five national championships in his first decade at Alabama, when it felt as if he would perpetually exist on some monotonous plane of success.

There was so much about this video that felt as if it had emerged from another dimension, beginning with the fact that Nick Saban appeared to know the intricacies of something called The Cupid Shuffle in the first place. The cautious side-to-side steps, the half-balled fists keeping fastidious time, and the face itself, that of a man letting loose with all the intensity of a librarian after downing a glass of chardonnay: Watching it for the first time was like being a kid and recognizing that your father just might be an actual human being.

II.

For much of his coaching career, the public viewed Nick Saban as a dour and colorless man. We believed that he was not satisfied with any one job because he was so irked by his own human imperfections; we believed that he was regimented and assiduous and often quite mean; we believed that he treated his players as faceless cogs in a machine, even when they were in the midst of a seizure; we witnessed how he complained about how winning national titles merely held him back from recruiting the next national title team; and how the only small joy he permitted himself amid his relentless implementation of his capital p Process derived from a box of processed treats available at the local Piggly Wiggly.

Through all those years, Saban felt like the avatar of the single-minded football coach, a man who apparently derived little joy from anything except the successful completion of that which was ordained by the Process itself. Part of the fascination of Saban’s most painful defeat, the Kick Six game against Auburn, lay in the fact that he was defeated by something he could not possibly have anticipated, one of the most unlikeliest plays in the history of modern sports.

Watching it live—and watching Saban stride off the feeling looking utterly helpless for one of the first times in his public life—was the equivalent of reaching adolescence and realizing, for the first time, that your father was not actually an omnipotent figure who could stem the forces of chaos.

In the end, we were all on our own. Even Nick Saban. He could not control everything. Time kept marching on. Toward the end, his protege, Georgia’s Kirby Smart, began to ever-so-slowly eclipse his own success. And that, I believe, is when he made the strategic choice to become more of a human being than he ever had before.

III.

Every so often during a press conference, Saban would display a sliver of the charisma that made him the greatest recruiter in the history of the sport. Sometimes, he would talk about sitting at his lake house with a wife he always referred to as Miss Terry, as if she could only be referred to in public with a former appellation for fear of disrespecting her authority. He spoke earnestly of his adoration for the Weather Channel; when he was feeling particularly introspective at a press conference, he would briefly mention looking forward to the day he retired, when he could sit at the lake house and stare out at the water and allow his mind to be at rest. He’d speak of the work he did at his father’s service station in West Virginia, and the perfection Big Nick demanded when washing cars, and how that shaped his ethos, and maybe he’d even briefly shed a tear. But then he’d quickly pivot away from the past and the future and jolt himself back to the present, the veneer raised once more with a sharp retort to a football question whose premise he found fundamentally flawed.

Football coaches are members of a species that is not given to aging gracefully. Maybe it’s the all-encompassing nature of the sport; maybe it’s because the militarized elements of the game make it seem more important to its most fervent believers than life itself. Joe Paterno stayed far too long and tarnished his legacy; Woody Hayes ended his run with an act of dispiriting violence. Bear Bryant quit, and then died shortly after. Jim Harbaugh told former Alabama quarterback Greg McElroy that you play, you coach, and then you die; Bill Belichick, Saban’s NFL analogue, ended his tenure in New England amid a blizzard of bad decisions and bitter recriminations, and still seems to be clinging to the hope that it’s not over yet.

I always assumed Saban would go out the same way; that it would be inevitably ugly to drag such a single-minded man away from the pursuit that gave him meaning. But as it turned out, Nick Saban—a man who so despised the unexpected—was given to surprises all along.

In retrospect, you could see it coming; there was a subtle mellowing, at least of his public persona, over the course of the past several years. He took more pleasure in telling colorful stories to an audience, in burnishing his own mythology, in providing incisive analysis on ESPN, and in bonding with talk-radio callers who existed to needle him, which led to perhaps my favorite Saban moment of all-time last fall…

IV.

As he grew older, Saban didn’t get as caught up in the winning and losing as long as he felt the Process had been followed to its conclusion. In his final season, he defeated Kirby Smart’s Georgia team to make the College Football Playoff, and even after a narrow loss to Michigan in the semifinal—where he lost to a perpetually unsatisfied coach—Saban completed what he believed was one of the most satisfying seasons of his career, one where his team improved dramatically, one where the Process mattered far more to him than the results. And then, having perfected his stoic philosophy, he decided he’d had enough.

Saban did not follow the path of so many of his predecessors; he did not cling to his identity until it was too late. He lived moment to moment, the way the Process demanded. And I suppose to a lot of people, that was the biggest surprise of all—that Saban was self-possessed enough to understand that the dance could not last forever.

Maybe I’m saying all of this because I’ve written about Saban so many times over the course of my career; maybe I’m saying all of this because I studied him when I was a young man and am studying him again as middle-aged man. Maybe he didn’t change that much at all; maybe it was me who changed. Whatever. The point is, eventually, it all comes together. Eventually, it all makes sense. Eventually, if you are lucky, you grow old enough to realize that your father knew what he was doing all along.

This newsletter is a perpetual work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Reply directly to this newsletter, contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please join the list and/or share it with others or consider a paid subscription.

This is an excellent article. The best one I’ve read on a one of the most complicated people in sports.

Very insightful. Good job.