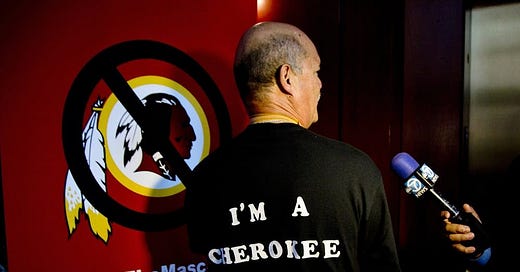

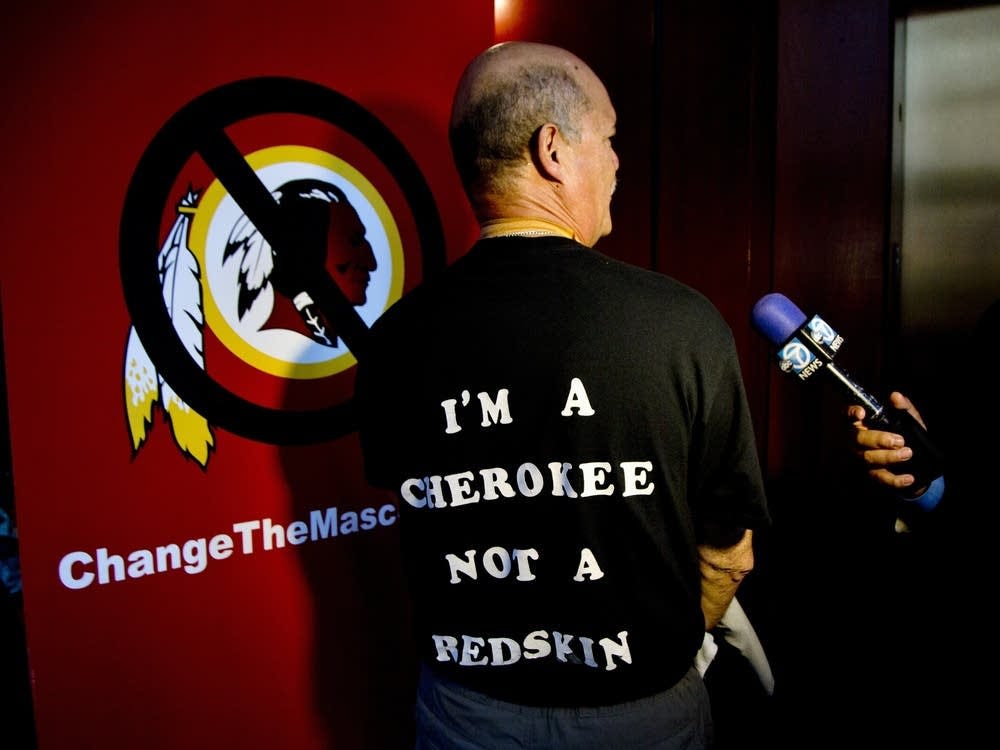

The (Merciful) End of the Mascot Wars? (1915-2020)

Or: Why does anyone care so much about a stupid nickname?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Throwbacks: A Newsletter About Sports History and Culture to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.