The Last Gasp of the Longball (April 2000)

Barry Bonds, San Francisco, and the end of the American century

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about the intersection of sports, history, culture and politics. Welcome to all new readers/subscribers, and if you like what you’re reading, please join the mailing list and share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing. (It’s still FREE to join the list: Just click “None” on the “subscribe now” page.) The best way you can help out is by spreading the word and sharing with others. That said, I have set up payment tiers, if you wish to “leave a tip”—I’ve made them as cheap as Substack will let me make them, which is $5 a month or $30 a year.

Author’s Note: This piece originally ran in 2020, in the early days of this newsletter. But given that Barry Bonds was seemingly locked out of the Baseball Hall of Fame for an indefinite period this week—and given that the tech industry is in the throes of a yet another upheaval—I figured it was worth re-upping here.

I.

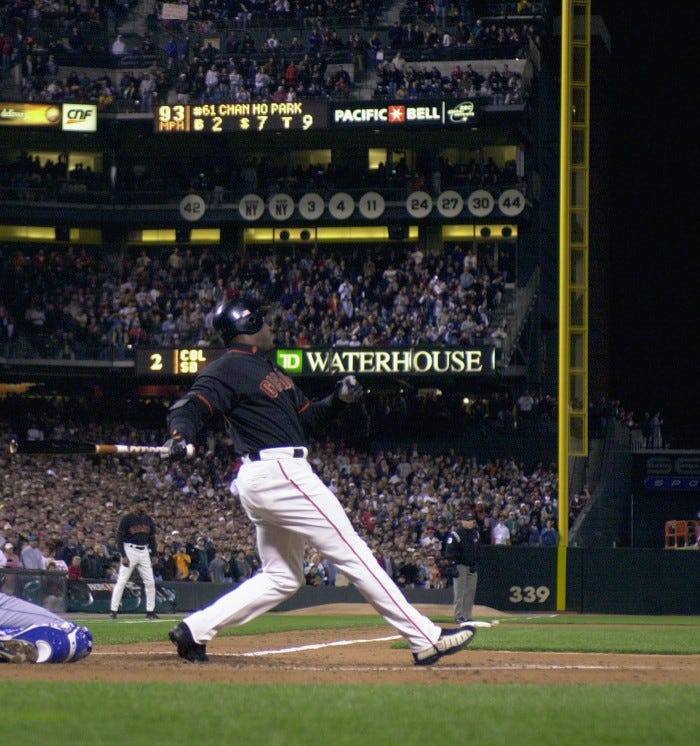

On the first day of April in the year 2000, Barry Bonds sauntered into a batter’s box, hoisted a bat above his left shoulder, and awaited a pitch from the New York Yankees’ Andy Pettitte. It was a statistically meaningless plate appearance at the front end of Bond’s 15th major-league baseball season, but to Bonds, this felt like the playoffs. It was the second exhibition game to be played in the San Francisco Giants’ picturesque new home, Pacific Bell Park, and neither Bonds nor any other player had hit a home run off live pitching in the first one. Bonds would later admit that he was “fired up”; he wanted to match the gravity of the moment, because nobody was more deeply wedded to the 20th-century history of San Francisco then the 35-year-old son of a former Giants player (Bobby Bonds) who grew up a baseball prodigy in the Bay Area and called Willie Mays his godfather.

Bonds swung at that first pitch from Pettitte, and in so doing, he established what became an essential part of his iconography: A ball soaring over the brick wall in left field, over the bleachers, over the standing-room porch, and out of Pacific Bell Park altogether, as Bonds stood at home plate and admired its flight path. Those home runs—and that ballpark, which two decades later remains one of the best aesthetic experiences in sports— captured the majesty and the beauty of a city whose local economy was soaring amid the first of the dot-com booms. And yet there was a duality and complexity to every one of those swings that we had no comprehension of in that moment.

Bonds’ first Pac Bell home run ricocheted off a pier and plunked softly onto the surface of an inlet of the San Francisco Bay newly dubbed McCovey Cove, after the man Bonds referred to as “Uncle Mac.” It was snagged from the water by a city health department employee who had steered an inflatable motorized dinghy across the bay from Alameda. He was immediately offered a thousand dollars for the ball. In keeping with the entrepreneurial spirit of the moment, he refused.

Five days later, on April 6 in Miami, Bonds hit his first official home run of the season, off a lefthanded pitcher named Jesus Sanchez. The next day, he hit another one, and on April 11, in the Giants’ first official game at Pac Bell Park, he did it again: Third inning, two outs, off Dodgers’ righthander Chan Ho Park, 499 feet to right-center field. By the end of April, Bonds had 10 home runs, which put him on pace to hit roughly 70 over the course of the season; over the course of the previous three seasons, his power numbers had steadily declined from 40 to 37 to 34. In 1998, he’d finished a distant eighth in the National League MVP voting, despite a wins-above-replacement number of 8.1, which was second-highest in baseball (behind only the Mariners’ Alex Rodriguez). No one credited Bonds much for his multi-category abilities, in part because he was a miserable human being for the media to deal with, and in part because baseball had become a sport driven by the longball, revived from the crippling 1994 strike by the booming summer of 1998, when Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa shattered home-run records.

We know now how Bonds reacted to that summer of ‘98, thanks to Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams’ iconic book Game of Shadows: He was consumed with both disbelief and envy. He presumed McGwire was doing steroids—and even if that were true, he viewed McGwire as a stiff player with no defensive skills who had none of Bonds’ versatility or athleticism. By 2000, Fainaru-Wada and Williams write, Bonds had become entangled with Victor Conte’s Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative, in an effort to keep up. And Bonds was not alone. That April was the first peak of baseball’s PED era: On Opening Day alone, five different players had multiple home run games. By the end of the month, the St. Louis Cardinals—McGwire among them—had set a major-league record with 55 home runs in a month. In all, 931 home runs were hit that April, shattering the record set the year before; by the end of the season, players had hit 5,693 home runs, setting a record that would stand until 2017.

But in April of 2000, we were a generally happy country. We wanted to believe this was happening for purely organic reasons, even if our subconscious told us that this couldn’t possibly be true.

II.

In January of 2000, roughly 20 percent of the ads for the Super Bowl were purchased by an impending graveyard of dot-com companies: Computer.com, E1040.com, Epidemic.com, EStamp.com, LastMinuteTravel.com, and of course, Pets.com, which would publicly implode by November, signaling the end of the first great Internet cycle. But we knew none of this yet. There were signs that the market was weakening, that these companies were overvalued, that the whole thing was a house of cards, but we hadn’t fully processed that the end was coming.

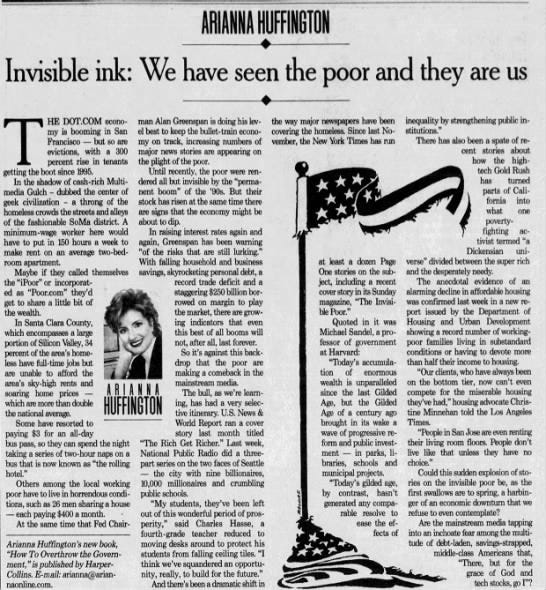

Roughly 69 percent of the country was satisfied with the way things were going in January of 2000, according to Gallup; and so when Arianna Huffington warned in a San Francisco Examiner column, the day after Bonds hit the first Pac Bell Park home run, that rising evictions and burgeoning homelessness might be a harbinger of a recession, and that it might lead San Francisco to become “a Dickensian universe divided between the super rich and the desperately needy,” it no doubt felt needlessly alarmist to many readers. (Irony alert: That Sunday edition of the Examiner included a mind-blowing 818 pages of news and advertisements. Five years later, Huffington’s own website, driven at first by pure aggregation of other outlets’ reportage and unpaid contributors, would help foment the Dickensian era of online journalism we’re currently suffering through.)

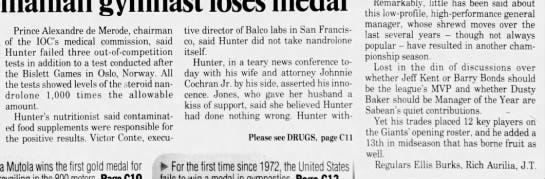

And so when Pac Bell Park opened and baseball’s home run boom reached a new high that April, no one had fully connected the dots, in part because information was scarce, but maybe also because we didn’t want to know. The ballpark was incredible; every Bonds home run was awe-inspiring. There was speculation about corked bats and juiced balls, but steroids, at least in reference to baseball, were hardly mentioned in the newspapers that month. Baseball had yet to outlaw androstenedione, the steroid precursor found in McGwire’s locker during the 1998 season; an Iowa State study had shown that andro likely had little effect on McGwire setting the record (we later learned that McGwire was powered by much more than just andro). During the 2000 season, the Sacramento Bee included this retroactively startling tandem of stories on its sports page—a denial from Victor Conte after C.J. Hunter, a track athlete under his tutelage, tested positive for steroids, next to an article speculating about whether Bonds had so thoroughly revived his career that he should win the National League Most Valuable Player award.

We know what happened next: The dot-com bubble burst even as Bonds kept hitting home runs, breaking McGwire’s record in October of 2001 (again with a home run off Chan Ho Park), three weeks after September 11. Over the ensuing years, Bonds’ connections to Conte became clear, thanks in large part to Game of Shadows; over time, baseball’s steroid era became a source of shame and skepticism, a measure of how naive we once were.

By April 2004, with Bonds on the verge of his final truly prolific season, Americans’ satisfaction with the state of the country had sunk to 41 percent; in San Francisco, the second tech bubble had already begun to swell and housing prices were about to begin another long and steady climb upward. Over the course of the next 16 years, our collective satisfaction with the country has never risen above the mid-40s. In that time, the Internet has evolved from a sea of curious start-ups to a handful of monopolistic conglomerates, and San Francisco has become a model for the Dickensian nightmare of rich and poor prophesized in Huffington’s column.

That April in 2000, we were a little bit hopeful and we were a little bit naive about our future, and we are still so ashamed of our own naivete during this period that Bonds and many other steroid users with deserving resumes are nowhere near being voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. I’m not sure how we come to terms with the duality of that era, any more than I know how we come to terms with the duality of the American experience two decades later. I suppose this is why Bonds’ legacy still seems so fluid, even now: There is great beauty even amid the ugliness, and it is history’s job to reconcile those things.

III.

Interview with Barry Bonds, July 2000

Additional reading:

Game of Shadows, by Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams

Love Me, Hate Me, by Jeff Pearlman

The New New Thing, by Michael Lewis

We Are Living in a Failed State, George Packer, The Atlantic, April 2020

Eleven Miles, but a World Away: The Warriors Make Their Last Stand in Oakland, Michael Weinreb, The Ringer, June 2019

This newsletter is very much a work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas? Contact me, or leave a comment below.