Sports Movies: Major League (1989)

Amid what was a golden era of baseball movies, Major League is increasingly the most resonant.

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics, and everything in-between.

If you like what you read, please click the button below, join the mailing list for FREE and please share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing.

And if you’ve been reading for a while, please consider a paid subscription to unlock certain posts and help keep this thing going—you’ll also get full access to the historical archive of over 250 articles. (Click here and you’ll get 20 percent off either a monthly or annual subscription for the first year.)

(If your subscription is up for renewal, just shoot me an email and I’ll figure out a way to get you that discount, as well. If you cannot afford a paid subscription and would like one, send me an email and I’ll comp you one, no questions asked.)

I.

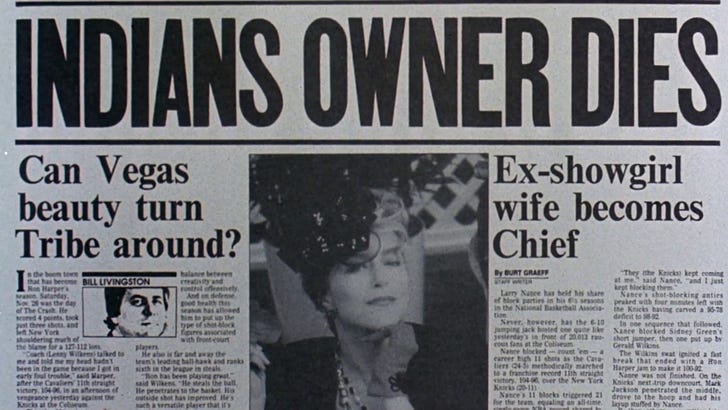

Sometime in the mid-1980s, a screenwriter named David S. Ward happened upon the hook he was seeking for a long-gestating project. Ward had grown up in Cleveland, and he was playing around with a wish-fulfillment story in which the town’s long-suffering baseball team—then known as the Indians—would win a pennant. Then, Ward—who knew something about grifters and con artists, having written The Sting, one of the best films of the 1970s or any other decade—read about the efforts of the owner of the Minnesota Twins, Calvin Griffith, to move his team from Minneapolis to Tampa, Florida, and the script came together from there.

Griffith had built an escape clause into his contract with the Metrodome if the Twins drew under 1.4 million fans for three successive years, and this inspired Ward to center his script, titled Major League, around a miserly female owner of the Indians who is doing everything she can to sabotage her own team so she can get the hell out of Cleveland. Learning about this connection between fact and fiction led me to read this 1983 Sports Illustrated profile of Calvin Griffith, which opens with the saddest lede I’ve read in quite some time (I’d like to credit the writer here, but SI so completely botched its archival pages that the writer is no longer listed on the page):

Calvin Griffith gets up from his desk with a groan and stretches black rubber half-boots over his shoes. He limps out of his office into the darkness, moving carefully across the parking-lot ice to the royal-blue Bonneville with the miniature baseball glove dangling from the rearview mirror.

Sometimes on the way home he stops at a grocery store. "I like that because you run into people who talk to you," he says. He drives to his suburban Minneapolis apartment and there mixes himself two vodka and tonics. "I try to keep it to two." He gets out the cocktail rye bread, toasts it and spreads it with cheese and maybe a little taco sauce. He turns on the TV. "Dynasty, Dallas, Falcon Crest, Knots Landing, Magnum, P.I., Dance Fever. I love to see those nimble bodies move."

And somehow, it only gets more depressing from there.

II.

I wanted to focus this newsletter more on the plot and characters of Major League itself, a film I find myself thinking about more and more these days. But I also recognize that pretty much everyone reading this newsletter knows the story by now; over the course of roughly 35 years and countless re-airings on basic cable, the archetypes in Major League have become infused into the culture of baseball itself. Every loose-limbed base stealer of the past four decades now evokes memories of Willie Mays Hayes; every erratic and hard-throwing reliever carries the DNA of Ricky “Wild Thing” Vaughn.

(I might argue that perhaps the greatest three minutes of the film are the first three minutes, the opening credits sequence soundtracked to the sheer acerbic brilliance of Randy Newman’s “Burn On.” It is perhaps the second-greatest opening montage that captures the grungy and resilient spirit of a city, right behind the credits of Dog Day Afternoon, scored to Elton John’s Amoreena.)

Major League is a broad fairy tale, but it works because it’s also grounded in reality. Ward based the character of Ricky Vaughn on hard-throwing pitchers like the Yankees’ Ryne Duren; he based Willie Mays Hayes on Rickey Henderson; he based the superstitious slugger Pedro Cerrano (stereotypical tropes aside) on the equally superstitious Alou brothers; and he based his miserly owner’s attempt to move the team on the pathetic saga of Calvin Griffith, a perpetually dissatisfied man who once proclaimed at a local Lions Club meeting that he moved the franchise from Washington, D.C. because there were more white people in Minnesota.

For those reasons, I’d always liked Major League—it is an almost impossible movie to dislike, especially when you factor in Bob Uecker—but if I’m being honest, I’d always liked other baseball movies of the era better. Bull Durham was a more highbrow and literary product for an aspiring writer to emulate; so, too was Eight Men Out. Yet I’ve been thinking more and more about Major League lately, and I’ve been admiring its subtle craft and Ward’s excellent writing and direction, and I presume this is for two reasons:

1.) Because stories about the wealthy and comically evil have become so prevalent, and

2.) Because I live in Oakland, California—a city worthy of its own Randy Newman song—and every so often I stumble onto a broadcast of the baseball team that used to reside here, and that feels increasingly as if its crossed over into the realm of fiction.

III.

The other day I happened upon the tail end of a broadcast of an A’s game, which always feel surreal, because the A’s now play their games at a tiny park in Sacramento, a city that they refuse to officially acknowledge as their temporary home. (This is probably one reason why they cannot even fill the seats of a minor-league stadium.) But these are the sorts of inexplicable facts that do not get mentioned on A’s broadcasts; in fact, in A’s World, the the city of Oakland has essentially been stricken from the map. (Oceania has always been at war with Eurasia, dude.)

The A’s lost this particular game; they lose a lot of games these days, despite having yet another infusion of intriguing young talent that they will no doubt either squander or give away for virtually nothing, as they have done over and over again in recent years. And then the postgame show began and it was anchored by a former major-leaguer named Steve Sax, who played one season for the A’s and grew up in Sacramento—and who, I presume, was willing to prostrate himself at the altar of a broadcast that feels increasingly like North Korean state television.

Steve Sax was a decent ballplayer who had a long career, and I imagine he’s a decent guy, but there was something remarkable about seeing him there, and realizing that the A’s were employing as one of their signature voices in this transitional era a guy who literally has a psychological disorder named after him—for a time Sax had what are known as The Yips, which means he couldn’t throw the ball from second base to first base. And the A’s are owned by a man named John Fisher, an owner who has his own version of The Yips, which mostly means he has a lot of big dumb ideas that he cannot see through to their completion.

Fisher is the heir to bumbling and miserly owners like Calvin Griffith; he is the real-life iteration of Rachel Phelps, the cruel fictional owner in Major League. The other day, Fisher held a groundbreaking ceremony for a new stadium he plans to build in Las Vegas, which he still does not seem to have secured much actual financing for; the groundbreaking was held indoors, which involved wearing hard hats for no apparent reason, then using gold shovels to unearth “red gravel on a raised baseball-diamond shaped platform inside a well-appointed tent,” according to longtime San Francisco Chronicle baseball writer Susan Slusser.

Nobody knows if Fisher will ever actually build the stadium he just “broke ground” for; nobody knows what he’s doing, or what he wants, or why he won’t just sell the team to Bay Area interests and put everyone out of their misery. In Minnesota, in 1984, Calvin Griffith eventually gave in and sold the team to a local owner who kept the Twins in town; as of now, Fisher seems to have no interest in doing the same, and Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred, the Roger Dorn of sports executives, is completely dug in on this entire idiotic scheme. “One official at Monday’s event said that Manfred was so irritated by negotiations during former Mayor Sheng Thao’s administration,” Slusser wrote, “that ‘he will never allow another team in Oakland.’” (If that kind of comical grudgery isn’t straight out of Major League, I don’t know what is.)

It is hard to take any of this A’s stuff seriously, because it all feels increasingly cartoonish. But then again, so does a lot of real life these days. And maybe that’s why it feels so comforting to settle into another re-watch of Major League—because it is a broad story where the underdogs prevail over the rich and the miserly and the obscenely cruel. It is a vision of a world where the worst people actually get their comeuppance. And maybe it’s just a fairy tale, but I suppose there’s a reason fairy tales exist, even—or especially—at a moment like the one we’re living through.

The Sports Movie Archives

The Program/Rudy

https://throwbacks.substack.com/p/the-programrudy-1993

Rollerball

https://throwbacks.substack.com/p/rollerball-1975

Semi-Tough

https://throwbacks.substack.com/p/semi-tough-and-the-age-of-bullshit

Moneyball

https://throwbacks.substack.com/p/moneyball-2011

The Bad News Bears

https://throwbacks.substack.com/p/all-we-got-on-this-team-are-a-bunchaapril

Dazed and Confused

https://throwbacks.substack.com/p/itd-be-a-lot-cooler-if-you-did-july

This newsletter is very much a work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please subscribe and/or share it with others.

FJF ⚾

Fellow Oaklander here, was at "Slide Jeremy Slide!" (the rest of the world calls it the "Jeter Flip") game, the "Moneyball" game, Sonny vs. Verlander, the dropped fly game, etc., etc., etc. Hundreds since the mid-90s, when I moved here.

Two scenes in silly movies that often bring me to tears are the death of Quellek ("By Grapthar's Hammer...") in "Galaxy Quest" and Wild Thing's last entrance from the bullpen. It isn't Charlie Sheen that draws the tears - as great as he is in that role - it is the crazy song & dance reaction of the fans. The fans are something that both of those movies get right. Baseball fan or Trekkie, the devotees are connected to by both films. They work because the people that made them didn't only love baseball and "Star Trek", but loved being fans and Trekkies. I know of no other baseball film like it in that way, and that connection, that empathy, pays off.

"Major League" remains one of my "comfort films". After sixty years, thanks to Manfred and Fisher, there's little comfort in baseball anymore, but I'll still put the movie on sometimes. I loved being an A's fan and joining in with the chants and cheers that ebbed and flowed over the years: A feisty bunch, wonky crowds with long-settled traditions at their core. I can't help thinking as I've experienced the Fisher debacle that neither he nor Manfred ever felt, nor could even ever feel, any such communion. I think team is gone, but I can still hope for some humiliating raspberry at the end.