March 11, 2020

One year later

This is Throwbacks, a weekly-ish newsletter by Michael Weinreb about sports history, culture and politics. Welcome to all new readers/subscribers, and if you like what you’re reading, please subscribe and share widely. (It’s still free: Just click “None” on the “subscribe now” page.) The best way you can help out is by spreading the word as much as possible. That said, I have set up payment tiers, if you wish to give something—I’ve made them as cheap as Substack will let me make them, which is $5 a month or $30 a year.

I.

Of all of ESPN’s 30 for 30 documentaries (including the one that regrettably incorporates my own visage), my favorite might be the one titled June 17, 1994. Directed by Brett Morgen, June 17, 1994 is a deceptively simple concept—it compiles raw news and video footage from a single historic day, when O.J. Simpson took to the freeway in a Ford Bronco and a series of memorable sporting events unfolded around it. There are no supplemental interviews; there is no narration. There is just the visceral feeling of what it was like to live through a single day in this country. Morgen claimed that June 17, 1994 was an effort to “look at the soul of America.” By staying silent and shepherding us through the moment, it transports us back to a time when the weight of those events had yet to fully sink in, a time when O.J. Simpson was still an American hero, a time when perhaps we were more inclined to believe in heroes.

Days like this, when it feels like everything is happening at once and our worldview is inexorably shifting, are how we measure the progress of history. Days like this are also how we measure our own progress through life. On June 17, 1994, I was an intern at a Dallas newspaper; on September 11, 2001, I was an aimless freelancer just emerging from a year of graduate school in Boston. And on March 11, 2020, I was living in Portland, Oregon, attending a screenwriting workshop as one of my classmates called out the notifications that kept popping up on her phone: Tom Hanks, the NBA, the president’s speech, the nation careening into lockdown.

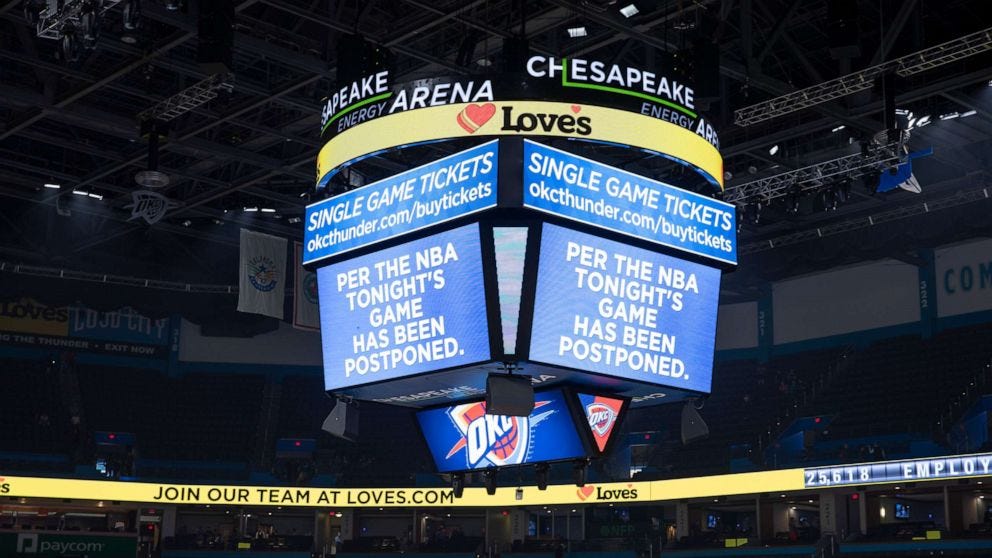

A few months back, ESPN’s 30 for 30 podcast produced an excellent episode entitled March 11, 2020. It is not quite as spare as Morgen’s documentary; it includes context in the form of interviews with a number of people about that day, including those who covered the NBA and watched as a game between the Utah Jazz and the Oklahoma City Thunder portended the dawn of a harrowing new era in American life. I remember my screenwriting classmate calling out the name Rudy Gobert, and I remember thinking: Rudy Gobert is a very good NBA player, and yet, many years from now, this is the only thing that most people will remember about Rudy Gobert. I remember texting a friend that night and asking if this was a bigger day in American history than 9/11, and he shook me off and said no, that it couldn’t possibly be, that there was no way the effects would linger for as long as the effects of 9/11 did.

To tell the truth, I didn’t really believe it, either. But a year later, and more than half a million lives later, here we are, still trying to process a day that makes June 17, 1994, feel entirely inconsequential by comparison.

II.

The first piece I wrote for this newsletter was in early April of last year. By then, we were locked down and hidden away, and I had taken to playing a rudimentary college football app/game/simulation called College Football Coach. It was something to do, a way to while away the time as sports disappeared from the calendar. Because just like July 17—and even, in a way, like September 11—sports had become an inextricable part of the history. It is now impossible not to think of the the NBA when you conjure the dawn of the Age of Coronavirus in America; it is impossible not to associate Tom Hanks and Rudy Gobert, a Bay Area man and a Frenchman who have almost nothing else in common, with one of the most harrowing days in modern history.

Listening to that 30 for 30 podcast brought all of that history together, for me, for the first time. In it, multiple people repeat some version of the thing that we all felt, which was, How could this possibly be real? But here is something the podcast did not mention, for obvious political reasons: The national mood was both surreal and incredibly stressful for years before March 11. There were no slow news days. Just noise. There was a fear, among a majority of Americans, that we were rudderless, leaderless; that if a catastrophe did visit, we were completely and totally screwed.

And then it happened. And that made March 11 hit harder, in many ways, than even September 11 did. It was frightening. It was unfathomable. As I wrote at the time, perhaps playing a crude sports simulation was the only way to make sense of a world that now felt more like a crude simulation than it ever had before.

III.

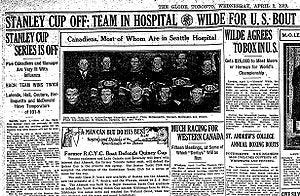

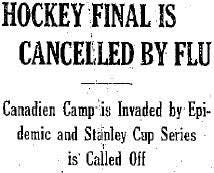

The first paid piece I wrote in the aftermath of March, 11, 2020 was for Smithsonian. I had done what I tend to do when the present moment becomes overwhelming: I had dug back into history, specifically the history of the 1919 flu epidemic, in an attempt to understand what we were going through and what we might be in for. And I learned that in 1919, as the flu epidemic appeared to be waning in much of the country, a hockey player in the Stanley Cup Finals had skated off the ice, feeling ill, and died a few days later in a hospital. That Stanley Cup Final went unfinished.

For that piece, I spoke to a historian who told me something that feels haunting in retrospect—how the hundreds of thousands of families who had lost people to the Spanish Flu, in those months when the Stanley Cup was being played and the pandemic had essentially been declared over, felt as if they’d been left behind. “There were thousands of orphans, and thousands of people who suffered a complete breakdown of family,” the historian told me. “It was a complete social change, even after the rest of the community had moved on.”

All that feels like its happening again, the way history does, and I suppose this says something about why this newsletter exists (and why I thank you for coming aboard to read it, and for telling your friends about it). So many people move on without processing the impact of historical events, particularly as they relate to something as seemingly inconsequential as sports. There is something fascinating to me about witnessing a moment of change, and then attempting to decipher what it means, and how exactly it alters the soul of America. What will last in our memories of March 11, 2020? How will it alter humanity as we know it? Those are questions we can’t yet answer, one year into this pandemic; those are questions that the 30 for 30 podcast (wisely) did not even attempt to speculate on, because it is very possible that we won’t be able to answer them until our brains begin to work properly again. You can’t really study something as history when it’s still so attached to the present.

“We’re trapped in our dollhouses,” one psychologist recently told The Atlantic’s Ellen Cushing, and we’re also trapped in the cycle of March 11, 2020, waiting for that moment of shock—and for the years of shock that preceded it—to wear away to we can understand how it’s going to change us.

This newsletter is very much a work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please subscribe and/or share it with others.