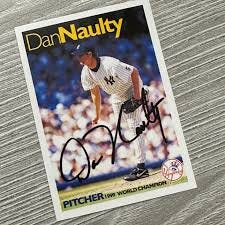

Bill of Goods (1999)

A journeyman pitcher, steroids, and the culmination of a quarter-century of lies.

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture and politics, and everything in-between.

If you like what you read, please click the button below, join the mailing list for FREE and please share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing.

And if you’ve been reading for a while, please consider a paid subscription to help keep this thing going—you’ll also get full access to the archive of over 200 articles. (And right now, you’ll get 20 percent off either a monthly or annual subscription for the first year.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Throwbacks: A Newsletter About Sports History and Culture to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.