A Throwbacks Conversation: Chuck Klosterman on the Cotton Bowl...and Many Other Football Things...

...including defunct rock festivals, Roger Staubach, his oddly conservative video-game strategy, and football's future (or lack thereof).

This is Throwbacks, a newsletter by me, Michael Weinreb, about sports, history, culture, and politics—and how they all bleed together.

If you like what you read, please click the button below, join the mailing list for FREE and please share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing.

And if you’ve been reading for a while, please consider joining the list of paid subscribers to unlock paid posts and allow me to expand Throwbacks’ offerings.

Here’s a link to get 20 percent off a monthly membership for your first year:

And here’s link to get 25 percent off an annual membership:

(If you cannot afford a paid subscription and would like one, send me an email and I’ll comp you one, no questions asked.)

I have known Chuck Klosterman for over half my life. We met at the Akron Beacon Journal, the newspaper where we both worked early in our careers. We spent a great deal of time eating lunch at Chinese restaurant buffets. We also lived in the same apartment complex, which was walking distance from a bar that we often spent time at with our friend David Giffels, where we would play the entirety of Led Zeppelin I on the jukebox and argue about Bob Knight and Ayn Rand. Often, we also wound up talking about football, and then Chuck and I were roommates for a while in New York City, where we watched prolific amounts of football, and started playing EA Sports College Football on the Playstation (a story that is recounted in Chuck’s new book).

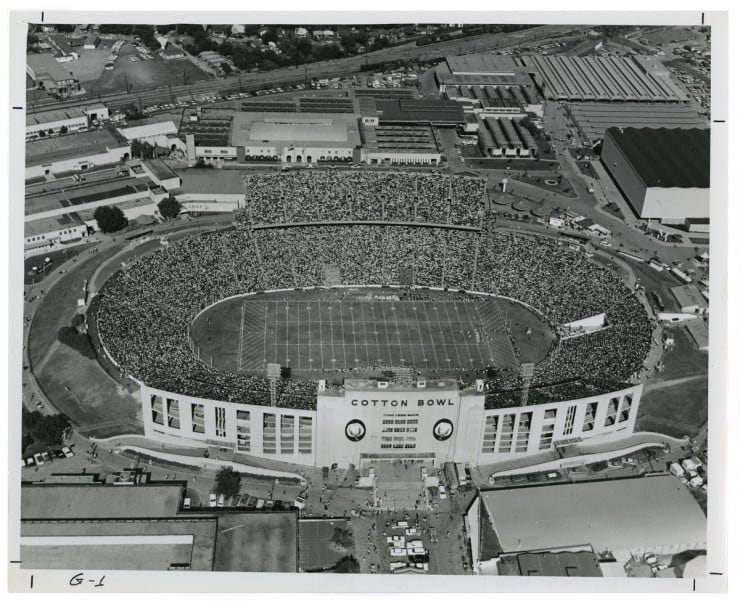

Football became a central theme of our friendship, which is not surprising because football is a central element of both our lives. And now Chuck has written a book called Football, which really only glosses over his deep emotional connection to the Cotton Bowl Stadium in Dallas, Texas. So that’s where this conversation kicks off.

MW: OK, Chuck Klosterman. So it certainly feels accurate, if not obvious, to state that over the course of the late 20th and early 21st-century, you are the human being I have watched and/or discussed and/or contemplated football with more than any other, and vice versa. Now you have written a book about football. That book, fittingly enough, is called Football.

I’m not sure what the first football game we watched actually was—I went through a strange period in the late 1990s where I kind of lost interest in the NFL, and you often mocked me for going to the mall instead of watching the Vikings play the Packers. But I believe our truest football dialogue began at an apartment complex in Akron, Ohio, in 1999 when we watched an undefeated Penn State team lose on a last-second field goal to Minnesota. You seemed genuinely shocked by my angered reaction to this defeat, as if you could not understand a normal human being reacting emotionally to a football game. But I have also learned over the years that while your Spock-like public persona still regards most “fandom” as oddly performative, you have certain nostalgic football-related soft spots. People, places, and odd occurrences that you are so connected with that you are often afraid to discuss them in detail, even with me.

However, now you have written a book about football (that book is called Football). And so I think it is time to better understand just how and why you connect emotionally to this sport in spite of yourself. And one of those things that gets at your soft underbelly is the Cotton Bowl, a 95-year-old stadium in Dallas, Texas, that still hosts the annual Texas-Oklahoma game, even if it no longer hosts the actual Cotton Bowl. Just the mere mention of the Cotton Bowl stadium inspires a kind of wistfulness otherwise reserved for your wife, your children, your dog, and Ace Frehley’s solo album. So please explain why a nearly century-old concrete edifice in a city where you’ve never lived—a stadium you’ve never actually been to in person, as far as I know--moves you nearly to tears.

CK: Ok, several points here.

First of all, thanks for asking me to do this. Second of all, I find it curious that you simultaneously accuse me of being both a Vulcan AND the kind of guy who does a lot of wistful weeping. Is that really possible? Spock didn’t even cry when he committed suicide. Thirdly, I was (indeed) shocked and appalled by your unhinged response to that Penn State v. Minnesota game. I had just met you two months earlier. I did not anticipate that level of anger. Obviously, I’d known other combustible sports fans throughout my life. I went to college with a guy who somehow managed to throw a TV through a window twice in the span of five years (once because of the Atlanta Braves and once because of the Georgetown Hoyas). Dudes get crazy. But your version of rage bordered on the grotesque. It was totally out of character and very much in line with the final moments from There Will be Blood. I actually thought you might throw me through a window (though I recall you living in a basement apartment, so the risk was low).

It is my fourth point that’s more relevant to this discussion, however: I feel like you’re inadvertently intertwining my feelings about Cotton Bowl Stadium with my feelings about the Cotton Bowl Classic.

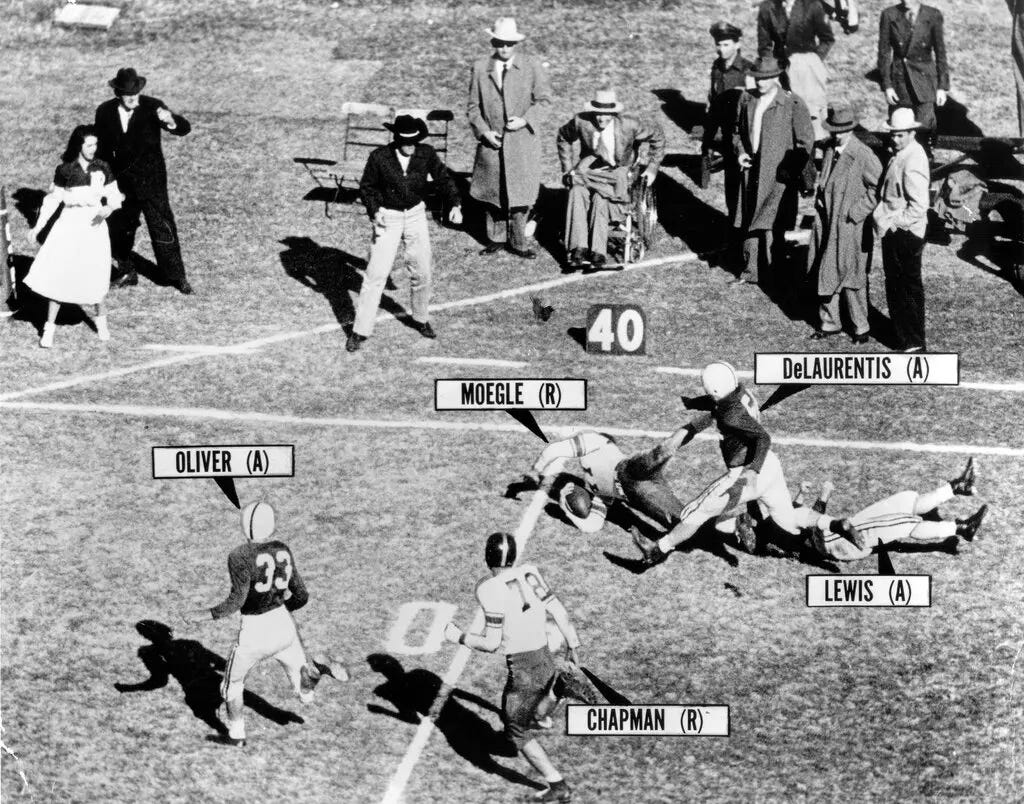

Is the Cotton Bowl the best stadium in America, and arguably the world? Yes. It obviously is, and most large-scale events would improve if they were staged in that venue. But that reality is separate from my feelings about the Cotton Bowl game, the most underrated and compelling of all the annual bowl games. The fact that the Cotton Bowl was moved out of Cotton Bowl in 2010 is a minor tragedy, both ideologically and semantically. But things like this happen. Life is suffering. In various summers throughout the 1980s, the annual Texxas Jam rock festival was temporarily moved out of the Cotton Bowl and staged indoors at the Houston Astrodome. That was terrible, too. But as a stoic, I can’t lose my shit over this stuff. I can’t throw a Mahogany Rush album through a window. I refuse to disrespect the memory of Tommy Lewis (or Dicky Maegle) by becoming a nutcase. They deserve better.

MW: So first, I need to clarify something here: I know you are given to retrospective exaggeration, but I don’t think my reaction to the Penn-State Minnesota game was THAT extreme. In fact, I think in the aftermath, we went to the record store, and then probably went to the bar and/or smoked a joint and watched the night game, which is pretty much the same thing we did every weekend for the next two years. Let me also clarify that I have never come close to hurling a television set through a window, though I once did scare our dog enough during a Penn State-Ohio State game that I found her cowering under a dresser. There are few things that I still feel emotionally connected to in the same way I did in childhood, and for me, Penn State football is one of those things. I felt stupid when it happens, and I recognize that stupidity even as it is happening, but I also think it is a healthy way to channel my own Proustian nostalgia. I get carried away on occasion, but I snap back to reality pretty quickly. Plus, I did apologize to the dog.

And here is where I need to admit that I wrote the above paragraphs before reading the final copy of the book. That is completely my fault, in part because you did send me an early draft but I hate reading books that aren’t actually printed, and in part because I think we’ve agreed that we know each other too well at this point to judge each other’s work objectively, particularly when it comes to something we’ve discussed as often and as thoroughly as football. (As evidence, I submit that we’ve spent at least ten hours alone comparing the careers of Michael Crabtree and Dez Bryant.)

That said, this book has surprised me.

And it has surprised me because of the reasons I hinted at above in the Cotton Bowl context. For years, I’ve tried to find a way in our discussions to reconcile your emotional connection to football with your cold-blooded and analytical public persona. And imagine my surprise when I realized that this felt like—at least to me--the overarching theme of the book.

Yes, it is a book about capital-F Football, and about the place of football in society, and whether it can hold that place in society given its inherent contradictions and given its fundamental brutality. (And in that sense, it is quite insightful.) It is also a book about football’s sense of regimentation and control versus the spontaneity and freedom that still manages to emerge out of that system. And here is what I’d argue: This is the most personal book you’ve written since your first one, a memoir about heavy metal called Fargo Rock City. Particularly in the chapter that covers Texas football, from Friday Night Lights to North Dallas Forty to the six-man game. While you don’t explore your deep love of the Cotton Bowl—and while you still often write with vintage Klostermanian detachment--you do explore your fealty toward Roger Staubach in a way I though you never would. This is you wrestling with a surprisingly deep level of emotion you are not quite sure what to do with, and are openly embarrassed to admit to. This chapter in particular is a Proustian love letter to football, to Texas, to Staubach, and oddly, to the city of Dallas, a place that you otherwise have zero emotional connection with.

So am I accurate? Do you deny this, even now that it is in print? Did it surprise you to articulate those words about Roger? And if so, perhaps you actually do feel the same things I do when I scare my hound while watching Penn State lose to Ohio State year after year, except that A.) You are more connected to people and places than to specific franchises, and B.) Your feelings are buried underneath more layers of practiced detachment, because you refuse to acknowledge (at least somewhat justifiably) that football should ever evoke this kind of emotion?

CK: I’m writing this on my phone from a Portland sports bar, which means I’m in a bar where the TVs are showing football on mute while the satellite radio system plays Frank Black’s “Los Angeles” and all the employees are tattooed women wearing stocking caps. But the Bills just ran a successful hook-and-lateral on fourth down, so that’s something.

Where to begin?

First of all, if you admit your emotional response to watching Penn State play Ohio State is disturbing to your own dog, any claim that you don’t totally lose your mind under these circumstances does not hold water. Your dog knows what’s happening. But what is more interesting (to me) is your on-going 28-year fixation over the fact that I am not emotional *enough.*

I think most writing (certainly all criticism and memoir) is an “emotional” experience. But I hate when people write in a *performatively* emotional style, because that’s so obviously fake. Before I publish a sentence, I probably re-write that sentence two or three times and re-read it 25 times. It sits on my hard drive for days or weeks or months before anyone else ever sees it. It just seems idiotic to pretend that I’m losing my goddamn mind on the pages of a book, in the same way it would be idiotic to scream at someone for something they did six months ago. But of course, the writing itself is still imbued with the original emotion that prompted the desire to express anything at all, and that’s what makes any writing compelling. That, I would say, is the goal: to trap subtextual emotion inside a paragraph that appears completely detached from surface-level emotion. But I think you are getting at something else here. I think you operate from the theory that I believe all emotions are a sign of weakness, so you *want me* to show emotion in order to say, “Ha ha! See, you are also weak and vulnerable.” But that is a misreading of my personality. I think I have the normal amount of emotions. I just try to keep them from annoying other people. This is not as hard as modern people seem to believe. You use the phrase “practiced detachment.” That’s a good phrase, and an accurate assessment. It does take practice.

But, that said, football is an emotional game, and it forces emotions to be confronted. Whoever is your hero when you’re seven is your hero for life, so Roger Staubach is my hero, even though he hasn’t played in 45 years. And my relationship to Staubach does feel weird to me, and a little uncomfortable. I don’t have any relationship to who I was when I was seven, yet I am obviously the same person, even though every cell in my body is different. And I’d agree that it seems insane to me that I care about football as much as I do, particularly since I’m never that invested in who wins any given game. I just want to watch ALL the games, mainly rooting for “the game to be good,” which means I am usually rooting for the team that is trailing, which means every game I watch will inevitably conclude with the team I’m rooting for losing in the end. This, I suppose, is one version of emotion.

MW: See, I don’t think this idea of you getting oddly emotional about a concrete bowl in Dallas, Texas, was meant to be a “gotcha” line of questioning. Oh, sure, perhaps it was an extremely mild poking of the proverbial bear, but mostly it was an attempt to gauge for an audience who might not know you as well as I do how you consume football (In ways that admittedly have often perplexed me), and what drove you to write a book about football, a thing that is inevitably emotional for you (though in strange and idiosyncratic ways). But I guess the question is, why write about football at all if that is the case? I remember when you had kids that you swore you would never write directly about your kids (and to be fair, other than a few passing mentions in this book, you’ve kept to that promise). Now, obviously, you are more emotionally attached to your children than you are to a Bowling Green-Toledo game on a November Tuesday, but there are many other things you could have written about, and here we are. And I presume that says something in itself.

And I think the scope of the book is fascinating within that context, because you’re essentially writing an obituary for a sport that is currently the most wildly popular institution in American life, and something that you just said that you unabashedly root for as an institution. It’s almost as if you are convincing yourself that your emotion is wasted—that this thing you love can’t possibly last given the societal pressures building against it over the course of time, and that the inevitable forces of progressivism will somehow wipe it out, no matter how you feel.

(It harkens back to your father’s reaction to the Doug Flutie Hail Mary, in which he essentially blamed himself for not believing it could actually happen, which is something I have also seen you do many, many times over the course of our football-watching careers. It is also how, as you write in the book, you treat a lead in our college football video-game contests: You become so weirdly conservative in style that you often actually do prevent yourself from winning. You’d rather go down swinging like Woody Hayes than embrace 21st-century modernism. You can only win by retreating into the past.)

But, to paraphrase an author you are intimately familiar with: “What if you’re wrong?”

Society today is radically different than it was 150 years ago, when football was born out of students on Ivy League campuses charging headlong into each other for no apparent reason. Yet football has only become more popular. So let’s say football DOESN’T wither from relevance. Let’s say it continues to serve as a proxy for America’s best and worst traits. Let’s say it is still a central fixture in this country in a hundred years and not a hollow throwback to a bygone era. What does it look like then? Does it become more wildly progressive in some completely unpredictable way? And assuming AI enables us to live to the age of 200, would it bother you if it did?

CK: This is a fascinating question. One would think, just from watching games evolve over the past 40 years, that the “deep future” of football would be a sport where teams never run the ball, ever. NFL teams (on average) attempted about 27 passes a game in the 1970s. Now it’s more like 35 attempts per game. There’s also the occasional game where a team throws almost exclusively. In 2013, Washington State’s Connor Halliday went 58-for-89 for 557 yards against Oregon, while the Cougars rushed only12 times for 2 yards. Since every straightforward statistic suggests passing the ball is more effective than running the ball, you’d think this would eventually become the thing everyone does all the time, in the same way basketball teams gradually realized that shooting 3s on virtually possession is the best strategy, even if it makes watching the game worse. But apparently, less straightforward statistics say the opposite. There is this analytics guy I sometimes seem on YouTube named Michael MacKelvie, and he has this clip…

…where he argues that the most mathematically effective offensive strategy is running the ball 54 percent of the time, even though the average passing attempt gains about four more yards than the average running attempt. The way he describes this is hard to disagree with. The only problem is that statistics only tell us about the past, and the past might have no relationship to the future you propose.

Something that’s been cool about the past five years of football is how coaches constantly go for it on fourth down, which used to never happen. I think everybody likes this. I bet even Reggie Roby would have liked this. The reasoning for doing this is that analytics suggest the potential value of an extended possession is greater than the 35+ yards of field position gained by a punt. It operates from the logic that it’s always smarter to gamble on 4th and 3 from midfield, regardless of the outcome. It’s simply a risk-reward math equation. But one thing I’ve noticed is that the skills of modern players have changed so much that stopping a team on fourth and 3 is increasingly impossible, making it less about risk-reward and more about mechanical practicality. If an offense is facing fourth and 3, the defense has to play the run, especially if the QB is a threat to run himself (which was super-rare in the 1990s and is now common). The defense needs 7 or 8 guys in the box. Quarterbacks have become so accurate and slot receivers have become so sure-handed that stopping a three-yard pass is very, very, very hard. You can put a player in motion and flare him into the flat, and there’s no way to get to him before the ball does. If a WR runs a stop route against man coverage and the QB throws to his back shoulder, the only way to break it up is by committing pass interference. In this scenario, the only real hope for the defense is for the quarterback to choke on the throw or for the receiver to drop the pass, two things that happen less and less. So it’s not just that trying to convert on fourth-and-short makes mathematical sense. It’s also that the players are better and the schemes are more sophisticated. And assuming this continues, that’s the part that’s hard to predict or visualize.

With football, I sometimes think reality can only be understood in the past and in the future. The present makes things hard to see. For example, everyone uses the shotgun now. Some teams often use it when they’re inside the five, which drives me crazy. There are high schools that only use the shotgun, and you’ll occasionally hear about a QB who never took a snap under center until he got to college. It now seems obvious that, as a formation, the shotgun is irrefutably better than the alternative. And that makes me wonder this: The Dallas Cowboys had the best winning percentage of any NFL team during the 1970s. They were also the only team of the 1970s to use the shotgun on a regular basis. So were these things connected? Did simply using this formation give them a greater advantage than anyone realized at the time?

MW: I think this is what makes football so fascinating, is that it evolves without us even realizing that it’s evolving. For instance, that insane Connor Halliday game you mentioned took place in 2013. At that point, things were crazy, mostly because Mike Leach, Halliday’s coach, was also crazy. (The funny thing is that I spent time with Leach twice—and with Halliday once—and both times he insisted that he would love to run the ball more than he did. And yet when Halliday was a senior, he threw for 734 yards in a 60-59 loss to Cal, a game in which Jared Goff also threw for 527 yards).

Anyway, there was that moment in the 2010s where we thought, “This is what football is going to be now.”(Nick Saban even asked out loud if this was what we WANTED football to be). Johnny Manziel was doing insane shit, the spread was raging, running backs began to be viewed as interchangeable cogs in the machine, and defense, particularly in the Big 12, seemed entirely optional. (On our group text thread, we often compared the obscenity of Big 12 games to pornography—in an overarching sense, not utilizing specifics, because that would be weird.) And I was, of course, enjoying the hell out of this, but you and our friend Jon Dolan, who tend to view football through a more reactionary lens, seemed pretty bothered by it.

But in the end, what happened was that football found a way to balance itself out. Now a variety of Mike Leach’s disciples have essentially incorporated the best of his offensive strategies, but have also adapted them to include more of a running game. Defenses have adjusted, with extra defensive backs and more mobile linebackers who can cover a spread offense. At Texas Tech, one of the surprise teams of 2025—a school where Leach once coached, and a school that developed a reputation for gratuitous passing stats—they threw the ball 34.7 times per game and ran it 39.4 times per game this season. Everything appears to have come back into balance. And I suppose that’s what gives me hope that football will survive. It seems to have a way of correcting itself.

(This, of course, does not alter the fundamental reality that football is a terribly dangerous sport that is increasingly shunned by more progressive communities, but it does make me think that perhaps the strategic element of football is often underrated, given that it is overshadowed by the violence. Maybe that’s a good thing that analytics have brought to the sport. I think the major test of this is going to be girls’ high-school flag football, which is already becoming kind of a big thing here in California. If that catches on, could it alter the perception of football itself? That’s a big assumption, I realize, but reality can only be understood in the future.)

Anyway, I suppose the best way to end this would be an exercise in “speculative nostalgia.” Let us say in 30 years, you have a grandchild who is fascinated by football in the way you were as a kid. He does nothing but consume old Cotton Bowl footage and Roger Staubach documentaries and videos of analytics nerds describing offensive tactics utilizing chessboard graphics. And he asks you, “Hey, you supremely bearded old fellow, if you had to evoke one player who truly defined football in 2025, who would it be?”

My answer would be Lamar Jackson. I know Mahomes is the obvious response here, but when I think about what quarterbacks have become and still might become, I think of Jackson first. In 30 years, it seems likely that half the quarterbacks in the league will probably play like Lamar, and many will be even more miraculously athletic and talented than he is. But it Is astounding to watch Lamar when he is at his best (though this season he was clearly not right). It kind of takes your breath away. It didn’t seem possible that someone like him would exist when we were kids—partly due to societal forces, and partly due to a lack of cultural imagination--and now he does. And I guess that’s why we can’t stop talking about this sport, even when we know we probably shouldn’t.

CK: Jackson is (of course) a good answer to your question, in part because he’s my favorite current NFL player and (I’m pretty sure) your favorite current NFL player, too. I don’t know if he really “defines” football in 2026, though. The way he plays seems unusually specific to him. I suppose he’s a little like an updated version of Michael Vick, or maybe the pro version of Allen Iverson in high school…but he doesn’t seem like the type of player a franchise could actively hunt for. As of today, he’s 10th all-time in yards per attempt, completes about 68 percent of his passes, and still runs like a pronghorn punt returner. In the open field, he’s harder to tackle than any running back, including Barkley and McCaffrey. So if some GM went into the draft and said, “We’re looking for another Lamar Jackson,” it would be a little like an NBA general manager going into the draft saying, “We’re looking for another Victor Wembanyama.” I suppose Jayden Daniels is the closest comparison, but not that close. In my view, the defining players of this era are the very big QBs with straight-ahead speed: Josh Allen, Justin Herbert, Drake Maye, maybe even Caleb Williams (though he’s not particularly tall). There was a time when the value of a mobile quarterback was that they could scramble and buy time. Now it seems better to have a classic drop-back passer who can also ram the ball upfield like a fullback, particularly on fourth down or inside the 10. These aren’t necessarily the best players, but they seem most reflective of the modern NFL. It’s a hard question.

Of course, on this issue, I must concede that you are a more reliable arbitrator. We’ve been playing EA College Football for over 20 years, minus the five years when it was banned. And I cannot deny that you were already playing a 2015 style in 2005. You were absolutely ahead of me on this, and the chasm still exists. From an offensive perspective, pornography came naturally to you. But at the same time, I feel I must be credited with the innovation of attempting 2-point conversations for no reason, at least two seasons before Chip Kelly had the same idea.

This newsletter is a perpetual work in progress. Thoughts? Ideas for future editions? Respond to this newsletter, Contact me via twitter or at michaeliweinreb at gmail, or leave a comment below. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please join the list and/or share it with others.

Love that picture with the names of the players. When I was a kid those photos were there every week on Sunday morning for the home team.

Great exchange between two of my favorites. I was thinking when you were discussing Lamar Jackson, one QB from our youth that I think compares, would have been Randall Cunningham.